Been there. Done that. Took the buyout.

“‘Hell freezes over’: National Post staff announce union drive at Postmedia’s flagship paper,” a headline on the Global News website said yesterday morning.

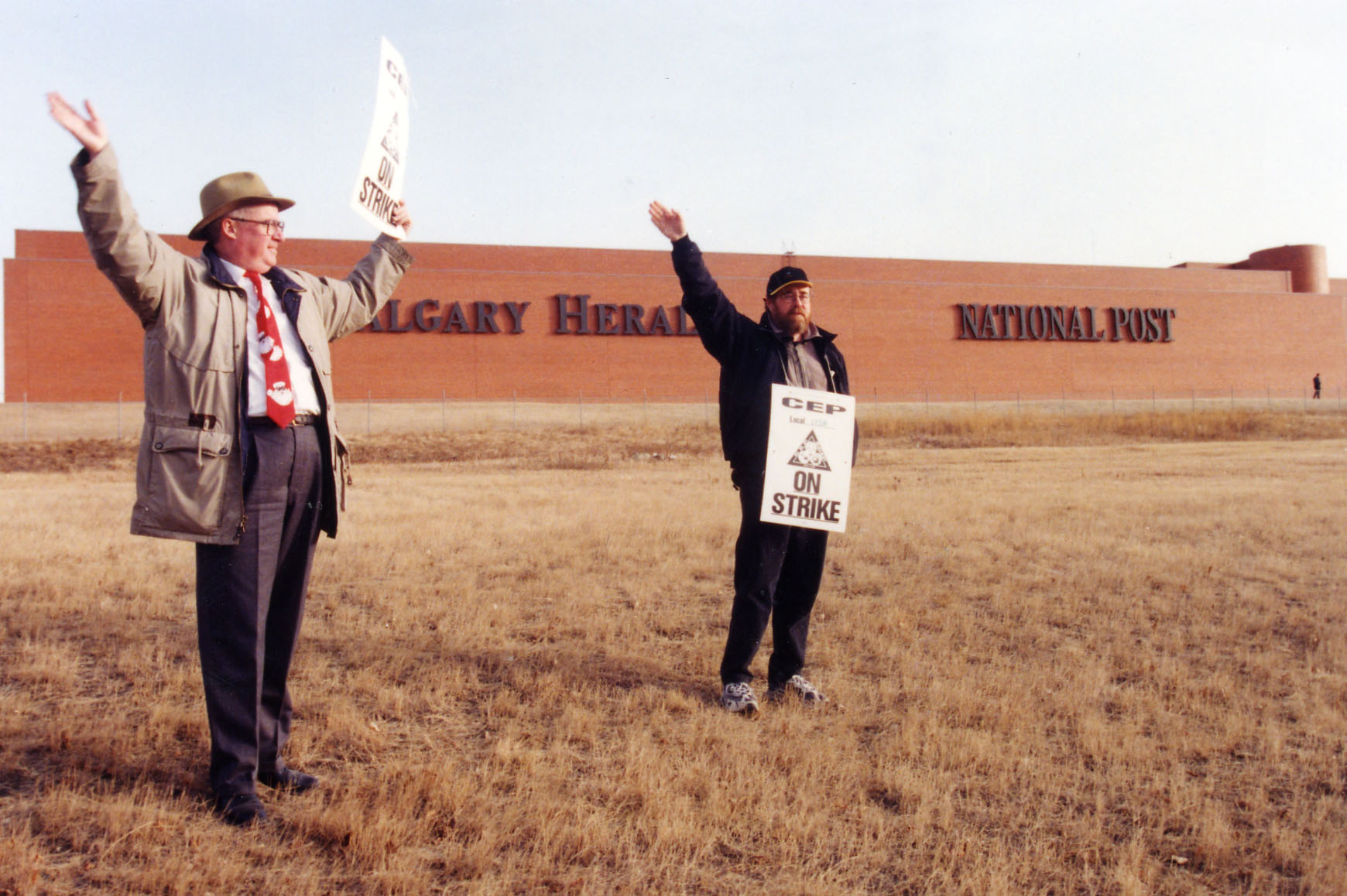

Less than two months from now, it’ll be the 18th anniversary of the start of the ugly eight-month strike at the Calgary Herald, a newspaper that was and is part of the same corporate fleet at the head of which the Post, rightly described as its ideological flagship, founders in the waves.

That strike ended in a humiliating defeat for the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, a career disaster for many of the strikers, and a catastrophe for good journalism in Calgary.

The ownership of the Toronto-based parent corporation changes from time to time, as the fortunes of the newspaper industry — which still seemed like a going concern back in November 1999 — decline. So does the name of the “Canada’s largest newspaper company”: Southam, Hollinger, CanWest Media, Postmedia … whatever.

But from an outsider’s perspective, it’s basically the same crowd running the company — with the same business philosophy and ideological blinders, both of which have contributed to the decline of the corporation to the point its collapse appears imminent. What about the internet? That’s only part of the problem.

The sad-sack state of the company, everyone seems to agree, is a key motivating factor behind the unionization drive at the Post — where senior editors and writers, the Global News reporter observed, “took pride in the paper’s non-unionized work environment that was seen to encourage a meritocracy.” (This was always baloney, of course, as anyone who has worked in the newspaper industry knows. But it’s comforting baloney if you happen to be one of the beneficiaries of the alleged meritocracy.)

Indeed, non-union Post staff were proud to mock the Herald’s strikers as childish socialist ninnies and occupants of a metaphorical “velvet coffin,” and to do their bit in the company’s ultimately successful effort to bust the union and force a generation of fine, experienced journalists out of the building and into new careers.

Different times, and mostly different people, I know. That’s not the irony.

The irony is that the heartfelt rhetoric of the Post’s would-be unionists today is almost identical to that of the Herald strikers in 1999 and 2000, before the strike ended in disillusionment and decertification. And it is true now, as it was then.

“We see unionizing as the best way to protect both ourselves and our readers across the country, who suffer every time the newspaper loses a great reporter, photographer, editor or designer to a buyout or a better-paid job with a competitor,” said a statement by the Post employees who are asking for a certification vote with the Communication Workers of America Canada.

The only difference between then and now is that in 1999 the writing was on the wall about what the company planned to do to its employees. Now it has all become reality — layoff after layoff, pension cuts, huge cuts to benefits, meagre buyouts, low starting pay, and an end to job security.

“We’re unionizing because we love this newspaper,” said the staff statement. “We want the Post and its newsroom staff to have long, bright futures. We have broad support among our colleagues and are planning to file for certification soon.”

Ditto at the Herald in 1999.

According to the Global account, one of the significant factors in making the success of the union drive at the Post a real possibility was disillusionment among the most experienced (and hence most valuable and at the same time most expensive) employees, who were being hit hard by the by the latest round of company cuts while Postmedia’s top managers rewarded themselves with rich bonuses for squeezing a few more drops of blood from the stone.

This too is an irony. These folks include the same people who complained endlessly in their ideological bloviations about “forced union dues” and how, at other papers, they were dragooned into unwanted union membership. (They were not. Under Ontario labour law, they had the option of not joining.)

Well, as I was taught as a lad in Sunday School, a change of heart and a sincere desire for redemption, even in extremis, is always welcomed by the angels.

And I truly hope to welcome the Post’s journalists to the union movement, and I wish them the best in confronting a difficult corporation at a difficult moment in history for a traditionally profitable industry that is unlikely to see such days again.

But I also hope they will forgive me if I say how much better off everyone in Canadian media would have been if the Calgary Herald strike had been as successful as its union drive, because, truly, a journalists’ union at the Herald would have done much to protect readers as well as employees, and to have ensured Postmedia treated the employees at its remaining non-union papers more fairly as the industry declined.

That was not to be. I am personally grateful. It got me out of the newspaper business with my health, sanity and retirement plans intact. I have proudly worked ever since for the trade union movement. Others were not so lucky.

Now? It will be a much harder row to hoe for the new trade unionists at the National Post. For many reasons, not least among them the survival of real journalism in Canada, I hope they succeed.

The author was the vice-president of CEP Local 115-A at the Calgary Herald in 1999 and 2000. When the company succeeded in busting the union, striking employees were given the option of returning to work, a requirement of the law, or taking a buyout. This post also appears on David Climenhaga’s blog, AlbertaPolitics.ca.