This blog is the third in the CCPA-NS series called “Progressive Voices on Public Education in Nova Scotia.”

The People’s Climate March showed an incredible level of solidarity across our planet and was a visible way to capture the news cycle and send a message to world leaders to act. But, climate change itself is not news. For those of us who are latecomers to the scene, Al Gore’s 2006 award-winning film, An Inconvenient Truth, should have alerted us. If that didn’t do it, surely the Fourth Report (2007) and the Fifth Report (2013) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change would have. We can no longer hide from the extremely unpleasant fact that climate change is the most serious crisis humankind has ever faced. We must take action commensurate to the weight of this remarkable challenge.

A new school year is an opportunity to ask: how is our education system preparing students to deal with climate change? Short answer: not very well. There are those conscientious teachers who take it upon themselves to figure out lessons that will bring a measure of understanding to their students, and there is the occasional short pilot program being tried out by a few others. But by and large, not much is being done, and most of what is done is not mandated.

We have an obligation to ensure that students develop a deep understanding of the dangers, urgency, and solutions to climate change. To do less at this late date is to foster an ignorance that makes youth susceptible to the world of misinformation, confusion, apathy and even denial and opposition to efforts to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Education about climate change must become front and centre in our curriculum at all levels of schooling and across disciplines. Real knowledge about climate change is at least as essential to the adults of tomorrow as is reading and writing, since it is they who will have to live in a world of increasing climate change and make the many, major decisions about how to do that.

Assuming that our school systems (soon) come to recognize the overarching centrality of climate change, what are the realistic challenges that need to be addressed? The first is to educate the educators. According to a recent study of Nova Scotia teachers, they expressed “high levels of concern about the impacts of climate change and reported relatively low levels of self-perceived climate change knowledge.” The biggest obstacle has already been conquered: the teachers are very concerned and therefore want to grapple with the issue. Supporting teachers through development of meaningful curriculum materials and professional development to teach about climate change needs to be a priority.

Secondly, how to fit this vast area of study into an already crammed curriculum? Clearly, there needs to be an urgent, major re-assessment of priorities. Indeed, climate change can be used as a lens through which to tackle other subjects: reading, writing, geography, politics, sciences, etc. As for programs and materials that would be useful to teachers, thankfully, good and even excellent resources already exist including in our own province. The most recent climate justice resources emphasize the critical relationship between climate change and social and economic justice. In addition, teachers must be encouraged to share the best of their own created materials and ideas.

The third challenge is to resist political pressure from industry to use materials that do not reflect the scientific consensus. Some fossil fuel industries and their allies have prepared teaching materials that focus on skepticism about climate change with an aim to getting them into the schools. Yet, we live in a world where 97 per cent of climate scientists now agree that we are experiencing climate change “very likely” due to human activities. This figure represents a clear consensus. There is nothing to be skeptical about. It is the climate change deniers who have injected a false skepticism into their so-called educational resources on climate change. These “resources” can obviously do a great deal of harm.

The fourth and most difficult challenge is how to present the truth about climate change to students without creating great fear and despair. This is a complex issue. However, the curriculum needs to focus on the solutions, both for mitigating climate change and for adapting to changes that cannot be prevented. Human beings are remarkably creative, and there is an astonishing number of solutions, big and small, out there. The curriculum needs to go far beyond teaching about the individual’s role in the 3 R’s — reduce, reuse, recycle — in the elementary schools, and emphasize the need for collective solutions to the climate-change problem. Such an emphasis serves to educate, foster responsible citizenship, and dispel fears.

A great deal of collaboration is required to make climate change a central component of public education in Nova Scotia. Teachers, students, administrators, parents, schools, unions, communities — our governments needs to ensure that they are supported to work together to move this forward now. The challenges are surmountable.

If we can get ourselves moving on this, in a few years from now, articles like this one will no longer need to be written.

Ruth Gamberg is a retired teacher. Presently, she volunteers on the Energy Action Team at the Ecology Action Centre and other local groups concerned about climate change.

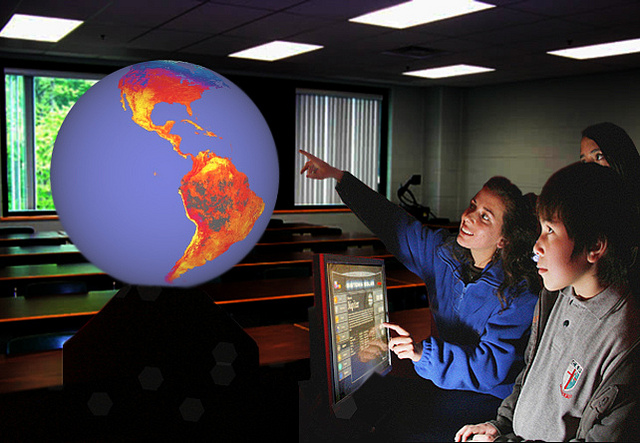

Photo: Global Imagination/flickr