I began to use the term street nurse around 1990 as a political term more than anything. It says to people: “Look, here in Canada, homelessness has become so serious that an entire nursing specialty called street nursing has developed.”

In 1998 Toronto Disaster Relief Committee, a group I co-founded, declared homelessness a national disaster. In fact, according to the World Health Organization, homelessness in Canada qualified as a social welfare disaster. Hundreds of organizations and numerous city councils ranging from Victoria to Toronto to Ottawa-Carleton agreed, passing motions calling for federal help on housing.

After we declared homelessness a national disaster, we won a new federal homelessness program but tragically not a national housing program. So, as my long time friend and colleague Michael Shapcott said, people were made more comfortable in their state of homelessness, but they were still homeless.

I describe Toronto as the epicentre of the homelessness disaster in Canada, although it can be argued there are multiple epicentres today.

Over the years, street nurses and advocates have worked on what I call the hotspots. These hotspots have included: overcrowded and unhealthy shelter conditions, forced outdoor sleeping, squats like Tent Cities, declining health and worsening chronic health issues, the heightened risk for extreme dangers such as tuberculosis or a pandemic and finally an extraordinarily high mortality rate.

Then this happened.

The recession hit and we saw more families with children become homeless. New hotspot: families with children.

Hate crimes towards homeless people began to be reported at the same time as municipal policies and police practices began to criminalize homelessness and target homeless people. New hotspot: hate and discrimination.

Street nurses began to confer with each other on how to deal with the effects of extreme summer heat and humidity on their patients. New hotspot: climate change.

The latest and most disturbing and dangerous hotspot I have now added to my list is this: the shifting policy framework in the country. The shift being to the right.

The once strong national movement for a national housing program has been transformed into one that looks very American.

Today’s advocacy focus is heavily weighted, not on developing a fully funded national housing program, but on the American approach to homelessness that includes an obsession with counting the homeless, developing ten-year plans to end homelessness and Housing First programs. Clearly, ten years into this obsession, none of these are working given the policy void that does not address affordable housing and adequate incomes. While there is enormous talk about Poverty Reduction and Housing First, poverty and homelessness has naturally only worsened in the absence of adequate social assistance rates, a better minimum wage and a massive housing build, similar to what we saw after World War II.

So, across the country, this shifting policy framework means that strings are attached to federal homelessness funding. This translates into shelters being forced to shut due to municipal funding decisions to divert money ‘upstream’ to Housing First initiatives. In many cities and towns men’s shelters, women’s shelters, drop-ins and aboriginal programs report losing municipal funding. In addition, community groups who come together to develop plans to open desperately needed shelters are told by city officials that will not be the direction of their government.

Some people ask me: “Are you still a street nurse?” I tell them: “Yes, I am and I’m working on the cure.”

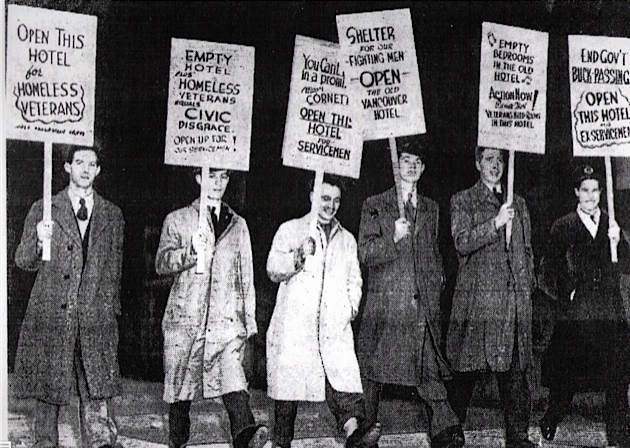

The cure is pure and simple. It’s about a Canadian value that vets of the Second World War fought for when they returned to Canada from the front. They valued the right to housing. Facing a housing shortage, these heroes protested, they rallied; they even occupied empty buildings in their fight. They won a national housing program that helped build the country we know. Our national housing program created 20,000 units a year — homes, apartments, housing co-ops, social housing, and shared housing — until the program was killed in 1993.

Language matters and today’s housing discourse is all about developing a national housing strategy not a national housing program. In Budget 2016, the federal Liberal government committed $2.3 billion over two years for “greater access to affordable housing.” The government has also indicated they will hold a consultation over the next year to develop a National Housing Strategy. Consultation, in this case, is a ridiculous concept given the enormous evidence already known about the need. I can only imagine the private developers’ interests that will drive a so-called consultation and strategy.

Canada Pension is a Plan. Old Age Security is a Program. Employment Insurance is a Program. Close to my heart as a nurse is Medicare, the name for Canada’s national health insurance Program.

Language matters.

Image from Toronto Disaster Relief Committee Archives