I have been sued for defamation. I mentioned my small role in the exposure 30 years before of a university administrator whose degree did not come from an accredited university. He wasn’t happy at the time, and, as it turned out, he still wasn’t happy 30 years later.

It was not a salutary experience. It didn’t seem to matter to the plaintiff that I had a perfectly serviceable defense. It still cost a lot of money, time and travel to defend myself.

I also worked for many years as an editor for the Toronto Globe and Mail and the Calgary Herald. I was expected to be reasonably aware of defamation law, and to do my best to reduce my employers’ liability for defamation suits. It also gave me an opportunity to hang around with a couple of good defamation lawyers.

So the following 10 points are a distillation of that experience. Yes, a determined plaintiff has a lot of advantages under Canada’s lousy defamation law, including the ability to use the law to blackmail defendants or shut critics up. Still, there are reasonable things you can do to reduce your risk of being sued for defamation, even if you can’t eliminate it.

1. Know what you’re dealing with

A defamation is any statement that tends to lower a person’s reputation in the eyes of others. Any statement. Remember that.

Defamation law is a problem for anyone who writes anything for publication in Canada.

The kind of defamation law writers normally have to worry about is a type of civil suit known as a “tort.” That is, a wrongful act that results in injury to someone’s property, person or reputation and for which the injured party can sue for compensation. This means any litigious nut can sue you just for mentioning them.

You’ve heard of “libel,” which is defamation in writing or other permanent form, and “slander,” which is spoken or in another impermanent form. Don’t worry about the distinction. They’re all rolled together under defamation in Canadian law. Just to make matters a little more confusing, “liable,” and “libel,” in this context, do not mean the same thing.

2. Know who can be defamed and who can defame them

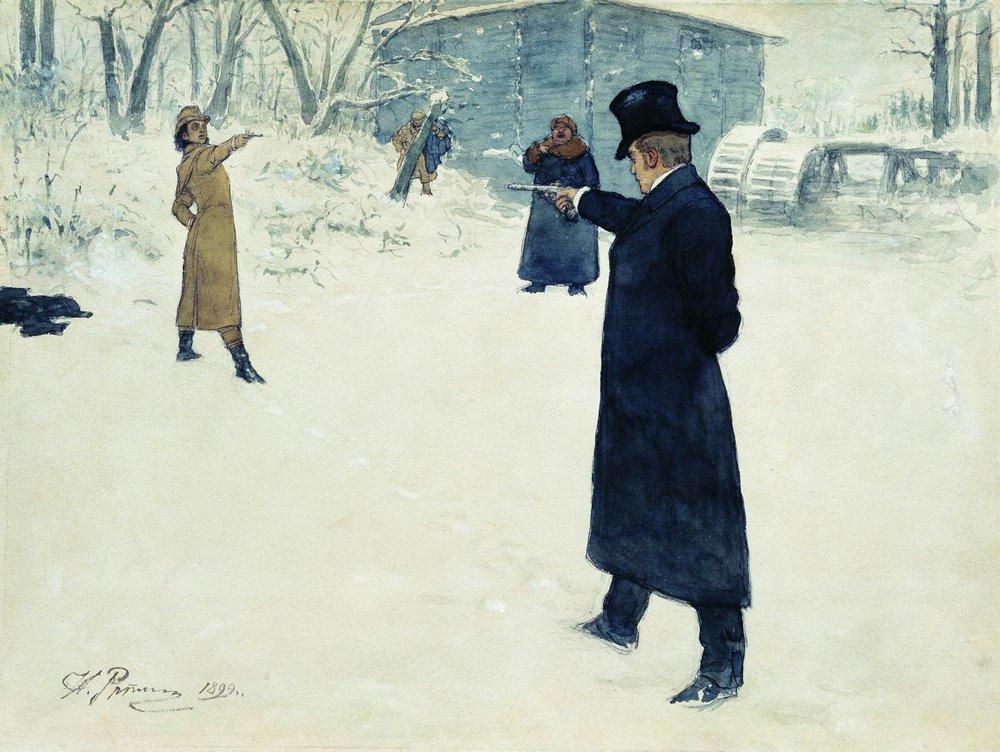

Libel law was created to keep rich folks from killing each other in duels. So the rules were harsh, because the social problem was serious. Canadian defamation acts still use the rules of libel, instead of those of the more sensible tort of slander, so the rules still give many advantages to the plaintiff — the person making the accusation.

Later, on the theory they are “legal persons,” this unfair and arcane law was extended to corporations, and now to unions and co-operatives. So such organizations have the same advantages as a natural person when they go to court to sue for defamation. This is a huge advantage for powerful corporations, and it is an outrage that this is permitted. It has allowed defamation law to become a powerful tool for corporations and wealthy people to suppress legitimate free speech.

Anyone in the “chain of publication” can be sued for defamation. This is a problem, because it means that plaintiffs can pick and choose whom they want to threaten. Not just the publisher or the author, but the printer, the internet service provider or the blog owner who allowed a defamatory comment! If nothing else, this is an argument for moderating comments by readers of your blog. Most commonly, however, the target of a defamation suit against a blog will be the author, the blog publisher, or both.

3. Understand that defamatory statements can appear anywhere

If you can publish words on it, you can be sued for the words that appear there. Twitter? Facebook? Your blog? Yes to all.

Still, there are some places that are relatively safer to publish your strong opinions. The bad news is they tend to be places where other people control access. To wit: letters to the editor of major newspapers, articles in major publications, organizations’ official publications, letters to employers or politicians, or heated exchanges at public meetings. Big publications have legal departments, and are more likely to have editors who know what they are doing, and this affords some protection. The latter two examples come under the two traditional “privilege” defences for defamation — that is, circumstances in which defamatory statements may nevertheless be published because the publication is traditionally deemed to be a public good.

Don’t press your luck, but it’s a fact that you also usually have more practical leeway to criticize a politician than, say, a businessman, because there’s a potential political cost to them if they sue you.

Defamation danger zones increasingly include blogs, Twitter, Facebook and other social media sites as word gets around to litigious individuals that defamation actions can be profitably pursued for comments in such forums. Moreover, commentary there tends to be cruder and angrier.

4. Canada is not the United States

Most of us would agree this is a generally good thing. But in matters of defamation law, Americans are at a significant advantage because of the longstanding commitment of the courts in that country to “the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide-open.” (U.S. Supreme Court, N.Y. Times vs. Sullivan, 1964)

Many Canadians assume the law is the same here, because they saw it on TV. Alas, this is simply not so. Canadian defamation law does not effectively protect your Constitutional right to free expression. It makes it hard for you to defend yourself if you are sued, even if the plaintiff has a lousy case. It makes it easy for the rich to shut you up.

5. Know the key problems with Canadian defamation law

- Damages are assumed, so the defendant must prove there was no damage done to the plaintiff’s reputation not to be held liable.

- The onus is on the defendant to prove there was no defamation.

- Even if you are in the right, defamation defences can be expensive. A defamation case that goes to court could cost participants as much as $30,000.

- Damages awarded seldom exceed $30,000.

- The most effective traditional defences — truth and “fair comment” — both require that the underlying truth must be proved in court. This can be hard.

6. Know your defences and write with them in mind

Well, geeze, this sounds gloomy. But if you know the defences for defendants — and write in a way that shows you understand them — you will insulate yourself against many suits. They are:

- It’s true (and you can prove it in court) — so say how you know.

- It’s a reasonable comment based on something that’s true (and can be proved in court) — so explain the logic for your conclusion, don’t just assume it’s obvious.

- It was said in a legislature or a court under oath (hallway conversations don’t count) — so say so.

- It’s an accurate report of something said in a legislature or a court, or a fair and timely report of a meeting that was open to the public — so make this clear.

- That the person defamed gave his or her consent to what you said — explain how.

- That it was said by a blogger or journalist on a matter of public interest and the author was diligent in checking facts and verifying allegations. This is a new defence recognized by the Supreme Court in 2009, called “responsible communication,” and it is far from clear yet how it will work.

Explaining the logic of a conclusion to signal a fair comment defence should be easy. Consider the example of the well-known business columnist who described a businessman well known for his defamation suits as “a fat, lying thief.” Before he did that, though, he explained that while the executive was known for mocking people about their weight, he was a little on the large side himself. Moreover, the columnist went on, the man had told in his biography how he misled an employee union in negotiations, and furthermore, on another page, how he had stolen a document when he was a young person. “Therefore, it’s fair to conclude,” he said, ” that Mr. X is a fat, lying thief…”

7. Don’t get mad — treat lawsuit threats as complaints

When someone phones up and says, “I’m gonna sue ya, ya bastard,” most of us get angry too. Stay calm. Listen. Take notes. Don’t get angry. And recognize the possibility that, while intemperate, the person threatening may have a legitimate concern. In other words, treat all threats of defamation suits as complaints.

It’s often surprisingly easy to calm people down and find a reasonable solution if we keep our wits about us. Often they don’t really want an apology so much as for the facts to be set straight. If you’re wrong, why not oblige them?

In practice, this often takes the form of a simple statement setting the record straight, followed by “[NAME OF PUBLICATION HERE] regrets the error.”

8. If the other party persists, consult a lawyer sooner than later

Yeah, I know, lawyers cost money, so this is a problem for many of us. But trying to negotiate with a plaintiff who is already lawyered up can cost you more, because you’re likely to make mistakes a lawyer wouldn’t. So if the “complaints” approach doesn’t work in the first five minutes or so, politely disengage and talk to a lawyer. Think about getting a “defamation rider” on your household insurance policy.

9. If you’re off base, be prepared to apologize

Remember, pride goeth before destruction and an haughty spirit before a fall. If you realize you’re wrong, a timely and sincere apology can save you a lot of grief. (Sometimes it doesn’t even have to be all that sincere.) Canadian courts will consider prompt, unqualified, seemingly sincere apologies in mitigation of damages.

10. Don’t quit fighting for what you believe in

We have a fundamental right to free speech. Our Canadian Charter of Rights protects it, at least in theory. Taking reasonable measures to avoid a law suit, or thinking about ways to respond to a suit, should never mean giving up the fight for what you believe in. Indeed, making that happen is the goal of the powerful forces in our society who use and abuse this law. Always keep in mind the need to keep up the fight — and consider adding defamation law reform to the list of causes you believe in.

David Climenhaga is an award-winning blogger published on rabble.ca, and a former Globe and Mail reporter and editor. He is a communications advisor to the United Nurses of Alberta.

Image: Wikimedia Commons