Posted below is a slightly longer version of my column in today’s Globe and Mail regarding the Harper government’s highly creative approach to making up labour law on the run.

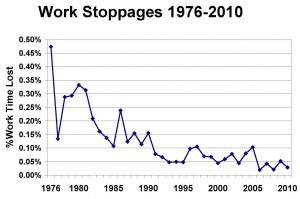

Also posted is a graph showing the dramatic decline (of 95 per cent or more) in the frequency of work stoppages in Canada since the mid-1970s. In 2010 only 0.03 per cent of work time was lost to work stoppages (including lockouts like U.S. Steel), just a smidge higher than the all-time postwar record low of 0.02 per cent reached in 2008 (source: calculated from StatsCan variables 4391647, 15856467, and 4391505, assumes 8-hour working day and 250 working days per year).

Here’s the Globe and Mail column:

The rule of law has suddenly been given a rather flexible interpretation by the Harper government in Ottawa, in the arena of labour relations. In just six months in power, the Conservative majority (fronted in this realm by Labour Minister Lisa Raitt) has intervened three times to end or prevent work stoppages.

The first was in June, when she announced (after less than one day of picketing) she would forcibly end a strike by CAW members at Air Canada. The two sides settled, sending one outstanding item (pensions for new hires) to arbitration. A new principle was established (call it Raitt’s First Principle): even at private non-monopoly companies, government can ban strikes.

Later that month, she waded into the Canada Post dispute. It was management (not the union) that locked out everyone and closed the doors. But Ms. Raitt used that as the pretext to legislate the posties back to work — imposing a wage settlement lower than what management had already offered. Raitt’s Second Principle was established: government can explicitly dictate wage settlements.

Then in October she pushed the boundaries of legal interpretation even further, calling in the Canada Industrial Relations Board to pre-empt a CUPE strike at Air Canada. She laughably invoked concerns about the “health and safety” of the travelling public (perhaps worried about too much airport coffee in the tummies of stranded passengers?). She further justified her actions on the basis of her government’s “strong mandate” in the May election (when Conservatives won 39.6 per cent of the vote). Raitt’s Third Principle is in fact a blank cheque: government can simply prohibit any work stoppage it wants to.

Each case represented an audacious willingness to intervene in labour-management relations, even in private companies. Each case moved the goalposts a little further. And now Ms. Raitt has speculated about amending the federal labour code so that the economy itself is defined as an essential service. That would codify Raitt’s Third Principle, giving government the explicit right to ban any work stoppage it deems offensive.

Of course, which work stoppages are prevented, and which aren’t, will remain a matter of judgment. Imagine if all work stoppages (not just strikes, but also lockouts — increasingly popular with employers) were prohibited. All disputes would then be settled by binding arbitration (as currently occurs with true essential services, like police and hospitals). But employers don’t want that approach, fearing that arbitrators may occasionally side with the union. The arbitrator in the Air Canada-CAW case did exactly that, sparking a bizarre decision by the company to appeal his “final and binding” judgment to the courts (an appeal since abandoned, wisely).

When employers hold the better cards (as they do in today’s unforgiving labour market), they happily go for the jugular — work stoppage or no work stoppage. Consider another epic dispute, which ended last month: the 50-week lockout at the U.S. Steel factory in Hamilton. There the company starved out the union with far-reaching demands to gut pensions and other long-standing provisions. The economic cost of that bitter, lopsided dispute didn’t slow the company, nor did it spur any level of government to action.

I estimate that the loss of GDP resulting from a 50-week shutdown of that plant was at least 4 times as large as the effects of a full one-week shutdown of Air Canada (something that never occurred). If government were truly concerned with “protecting recovery,” why didn’t it end the U.S. Steel lockout? True, steel falls within provincial (not federal) jurisdiction. But Ottawa had plenty of leverage if it wanted to act — not least being U.S. Steel’s galling violation of the production and employment commitments it made when Ottawa approved its takeover of the former Stelco.

In this case, where workers held little power, government stood idly by. It’s only when workers have a little leverage that government acts powerfully to “protect the economy.”

We shouldn’t forget, either, that the extent of work stoppages has already declined dramatically during the neoliberal era, reflecting both the gradual decline of unionization, and more importantly a more dramatic decline in the propensity of union members to go on strike (offset somewhat by the increasing propensity of employers to lock their unionized workers out). In 2010 work stoppages (both strikes and lockouts) accounted from 0.03 per cent (i.e. one-thirtieth of one per cent) of all work time in Canada’s economy; that’s a 95 per cent decline from the strike-happy days of the 1970s.

In that context, trying to pretend that union work stoppages are really a major problem facing Canada’s economy is far-fetched, to say the least. 0.03 per cent of a year’s working time is approximately 37 minutes — barely enough to run down to Timmie’s and back for a double-double. And in today’s labour relations environment, those stoppages that do occur are more likely to be driven by management, not by the unions.

There is no doubt that Raitt’s actions have been popular with many Canadians. And there is no doubt that work stoppages cause economic inconvenience and disruption. But because something is unpopular or inconvenient, does not give a government moral authority to take away rights and make up the law as it goes — even if it does hold a majority of seats in a parliament.

Jim Stanford is an economist with CAW. This article was first posted on The Progressive Economics Forum.