Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a monthly supporter of rabble.ca.

Hardly a week goes by without an article in a major scientific journal about the diversity of microorganisms living in and on our bodies. Few microbial species can be grown in pure culture, but modern DNA sequencing techniques have unleashed a flood of information about microbes associated with humans. Google Scholar analysis of the term “human microbiome” shows fewer than 1,000 articles between 1970 and 1999, 3,000 articles between 2000 and 2009, and over 17,000 articles since 2010.

This is not just idle curiosity. When scientists launched the international Human Microbiome Project in 2007, they noted that “rapid, and marked, transformations in human lifestyles are not only affecting the health of the biosphere, but possibly our own health as a result of changes in our microbial ecology.” A 2010 review paper, “Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease,” explains that human-associated microbes influence us “at nearly every level and in every organ system, highlighting our interdependence and coevolution.”

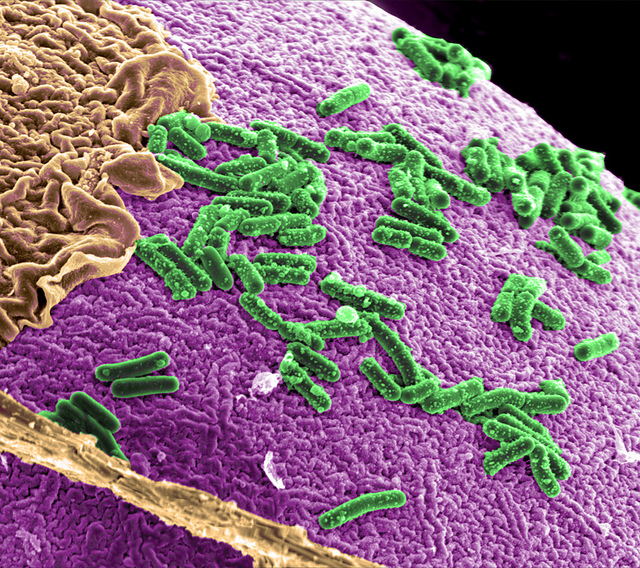

We are made up of more non-human cells than human cells — by a large margin. Authors of a 2006 paper in Science estimate that we have 10-100 trillion microbial cells in our gut alone, roughly ten-fold more than all our human cells. We have about 100 times more microbial genes than human genes in our bodies.

Our human microbial ecosystem

Our normal complement of microorganisms becomes established within a week or two of birth. Babies benefit from microorganisms transferred from their mothers during a normal birth, whereas C-sections can lead to a weakened immune system. Breast-feeding helps overcome immune deficiencies.

A 2012 paper, “Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome,” reports on microbial analyses of saliva; soft tissues in the cheeks, gums, palate, tonsils, throat and tongue; tooth biofilm above and below the gum; skin from behind each ear and the inner elbows; nostrils; vagina; and feces for 129 males and 113 females. Researchers combined their samples into five basic microbial habitats: oral, gastrointestinal, nasal, skin and urogenital.

Their results showed that show that our microbiome is highly diverse. Each of us has a unique and dynamic microbial ecosystem. Changes in diet — such as switching from eating meat to a vegetarian diet, or vice versa — can quickly trigger dramatic changes in our microbial flora. Major, deleterious alterations of the gut microbiota are associated with excessive weight gain, but can be reversed with weight loss.

While microorganisms occur throughout our digestive system, from mouth to anus, they are most abundant in the large intestine, or colon. They comprise about 80 per cent of our feces.

Many gut microorganisms are beneficial. They detoxify ingested carcinogens. They manufacture vitamins. They prevent harmful bacteria from dominating our gut, helping us fight off infections and avoid diseases ranging from irritable bowel syndrome to colorectal cancer.

Helpful microbes also aid in digestion and absorption of nutrients. When we eat, we’re not just feeding ourselves. We’re also feeding our microbial partners. If we’re trying to lose weight, we should be happy to share — this means fewer calories going to our waistlines.

Keeping our microbes healthy

Much like spraying Agent Orange on the jungles of Vietnam, antibiotics can lay waste to human microbial ecosystems, with potentially life-threatening consequences. Recurring hospital outbreaks of harmful gut organisms like Clostridium difficile are spurring research on ways to restore a more “normal” microbial flora after antibiotic use — including “probiotics” and fecal transplants. Incidence of asthma is correlated with treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics during early childhood.

We’ve come a long way from the “germ-free” 1950s, but scientists still debate things like the safety of hand sanitizers. A skin microbiome study notes that, “Our current society paradoxically strives to colonize our guts with probiotic yogurts, but sterilize our skin with hand sanitizers.” While their use reduces transmission of viruses and bacteria from person to person, they may also find their way inside our bodies and cause harm.

Science is still uncovering the downsides of anti-microbial agents and other chemicals found in various consumer products. One clear recommendation is to avoid products with synthetic fragrances.

Food that is good for us also keeps our microbes healthy. This means a mixture of vegetables and fruits, lots of fiber, whole grains, not too much meat, keeping away from over-processed and over-packaged foods, eating organic food where possible, and avoiding over-eating.

Ole Hendrickson is a retired forest ecologist and a founding member of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley.

Image: Three-dimensional human intestinal cells cultured with gut bacteria. Courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.