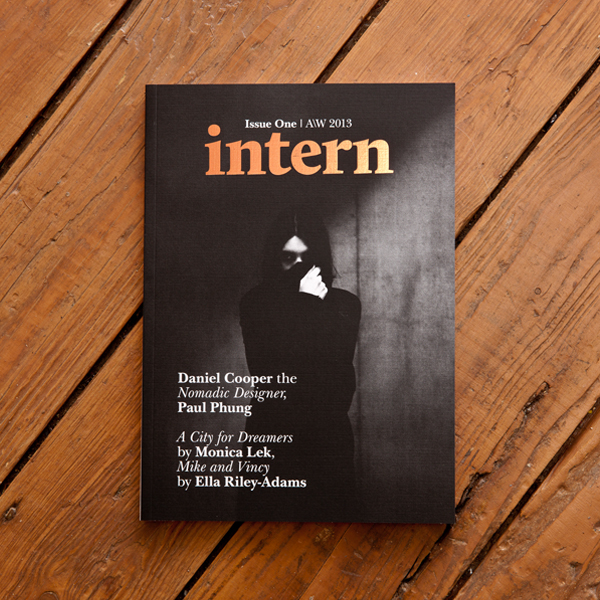

Meet the talent. Join the debate. That’s the promise of Intern magazine, a new, UK based bi-annual print publication that explores life for the growing class of young workers in the creative industries who work for free in exchange for exposure, contacts and international mobility.

Editor-in-Chief Alec Dudson is all too familiar with unpaid internships, having completed two before striking out on his own to start Intern. His goal, inspired by his work experience, was to create a well-designed magazine that explored internships from all angles — the good, the bad and the ugly.

The first issue, supported by a Kickstarter campaign that generated a ton of press worldwide, includes stories about a graphic designer who did a blitz of internships across Europe, an English organization that is fighting for intern rights and photo essays from several young photographers.

Dudson’s goal is two-fold: get people engaged with the intern issue and, with any luck, get the talented artists that contribute to Intern a job that actually pays.

We spoke a bit about the inspiration behind Intern, why he has to pay everyone who works on it and what’s in store moving forward. This is a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

Why did you want to make the magazine?

Magazines were something I wanted to get into. I had been working in bars part-time while I was finishing my studies and then went on to work full-time in them for about a year and a half after graduating. I got invited to get involved in a website with a friend. That was kind of what led me into magazines as it was an online magazine of sorts.

I had just gotten to the stage in my life where I knew I wasn’t going to work in a bar all my life — or at least I didn’t want to. I was waiting for something to come along that I really wanted to forge a path into. It ended up being magazines.

I did a three month internship in Milan with Domus, a design and architecture publication. Then when I came back to the United Kingdom I moved to London and got an internship with Boat, a nomadic travel publication. I stayed there for about seven months.

When that wound down it wasn’t like I was getting any job offers to work in magazines. Seemingly, I was no better off in terms of getting paid work than I was in the first place.

So initially Intern was as much a kind of potential for me to stay working in magazines. I convinced myself I had enough experience to give it a go and knew roughly what to expect. It was a case of finding the subject, and the idea I kept returning to was this idea of internships, I guess born of my own experience.

In the months I’d spent doing it, I’d come across a lot of people who were in the same situation as me. The more time I spent in the magazine industry the more I realized that interns were a relatively integral part to pretty much most of the magazine operations that I aspired to maybe work for in the future.

It just seemed like they were underrepresented. From there on in it was very much a case of working out if this was going to be what we are going to focus on and what the tone is going to be.

Reading through Intern it doesn’t seem like you are taking a side in the debate. How did you get to that editorial vision?

If the stories in it were going to have any real value then the magazine as a whole, or as near as possible, had to be unbiased.

Our tag line is “meet the talent,” which is the showcase element to it, and “join the debate,” which is the sort of discussion side of it. I don’t think you can use a word like debate if what you’re presenting isn’t an open debate which gives people of various standing and various opinion the same opportunities to say their piece without you talking over them.

It had to be as unbiased as possible. The part that we kind fall down on a little bit is that we make a point of paying our contributors — so that maybe gives away my personal stance on things.

A lot of people that I talk to in Canada feel that you can’t avoid doing an internship even if you are against them, especially if you are in a creative industry like magazine editing.

That’s one of the biggest challenges to anything really changing when it comes to unpaid internships because it’s ingrained in the culture. I didn’t know much about internships, but I was pretty much told if you’re going to work in magazines you start by doing internships.

I was able to make it work. I was very lucky in that respect, but it wasn’t spectacular or anything. I cycled everywhere I went so I didn’t spend money on travel and I stayed on friends sofas for the entirety of my seven month internship in London. I generally moved house every week — two weeks max — so not to get under anyone’s feet. I got a part-time bar job. I was working a 30-hour week in the bar, 40 hours a week near enough with the magazine unpaid. But you know, I was lucky to be able to manufacture that situation. That was not really an option for everyone.

The way you’re talking about it — being lucky to be able to do it and to find a way to make it work — I’ve interview a lot of interns and they use that same language.

Why do you think that is? Is it getting access to these contacts or is it getting these positions where you do get to travel? It seems to me that another major component of these internships is that you can potentially go to say New York City – or here Toronto is the big place where everyone goes.

I guess what it boils down to is: do you have the money to do it and do you have the money to travel?

If you’ve got the money to take the risk of moving to a city and working unpaid then that’s great. My situation is a little bit different because I’m older — I was 28 when I set out on my first internship last March, so with that I worked full time for a few years. I had a little bit of money that could kind of act like a buffer.

I guess language like “lucky” is used by people who are financially able to put themselves in that situation because it’s not something people are comfortable admitting to or certainly don’t want to crow about –that they are financially stable enough to make it work.

The people that really want to make it work will find a way of doing it even if they are working three weeks packed into one. It’s not really conducive to having a fair crack at the whip.

All of those problems — they don’t disappear, but you at least level the playing field — if you’re paying someone minimum wage.

When you decided to put the magazine together you knew you wanted to have this broad vision. How did you go about finding people who could show you the whole spectrum of experiences?

Our issue zero that was released when the Kickstarter was on that represented the toughest move because at that point, when I was approaching people, I was just a guy at the end of an email with an idea.

Once the Kickstarter was online that kind of flipped on its head. People connected with the idea. I think about 60 per cent of the content for issue one was pretty much locked in by the time the Kickstarter happened. The rest kind of came about as result of it.

There was always the intention to try and make it as international as possible and to try and get as many people with different angles as we could.

One of your other stated goals about the magazine and the website is showing off peoples’ talents and trying to get them hired. How did that idea develop?

I guess that goes back to the situation I found myself in.

Nobody was about to start paying me to work in magazines. When I was at Boat I found out that one of the publications that I, at the time, really aspired to write for somewhere down the line didn’t pay their contributors.

The system seemed completely broken to me.

So trying to help people fill in that gap from graduating to finding work to the point where they can call themselves a photographer or a designer was always going to be pretty central to Intern.

It would completely undermine the concept of Intern if I just took advantage of peoples’ work and published it without pay.

I really like the idea that people are getting paid and can start transitioning to a more professional identity through a magazine called Intern when they can’t do that other magazines that are supposed to be professional.

That’s another thing — they are all called contributors when they are involved with us. One source of incredible frustration is that ever since we started the Kickstarter, I get people all the time saying, “can I intern with you?”

Anyone who’s worked on Intern gets paid. Albeit it’s not as much money as I would like to pay them, but there’s not a lot of money kicking around.

The way this project is designed financially is that as much as possible I do the work so that I don’t end up paying other people to do that work so that when it comes around to the issues I can pay my contributors as much as I possibly can.

The initial response to the project was huge. Going forward, how do you keep that momentum going?

That’s been pretty tough at the moment. This is all completely new to me and the business side is a complete and utter learning curve and press is another learning curve. Somehow the timing was really fortunate and we drummed up incredible press, particularly in the United States, during the Kickstarter campaign.

Trying to build that momentum and keep it going is a huge challenge. When you only have a few 1000 followers on twitter they don’t want to hear the same shit day in, day out — that side of it is a learning curve as well.

If we can get the magazine out there enough and enough people hear about it, then hopefully the quality of the content and the magazine itself will do the talking.

I try to use social media as much as I can to gauge opinion. Any feedback, positive or negative, is great for me. It’s always interesting to see people’s reactions, because your first issue is never going to be perfect. The moment you think you’ve produced a perfect magazine you might as well quit because you are on a slippery slope.