In 2018, seven provinces and two territories will be holding provincial and/or municipal elections. While voting is often seen as a perfunctory task, we should be identifying each election as a site of struggle where real change can happen. Upon closer examination, social media tools, in spite of their potential pitfalls and flaws, take electoral politics far beyond the obligatory act of voting to facilitating the building of robust electoral online social movements.

The 2015 federal election demonstrated that through building a social movement, elections allow for shifts not only in leadership, but also in the values and priorities of a nation. In many respects, social media has changed the relationship between the individual private act of casting a ballot and public social movement struggles for political change.

Prior to 2015, political engagement in Canada fluctuated at low levels, far from T.H. Marshall’s idea of a robust and engaged citizenship. Writing in 1950, he defined citizenship as having multiple dimensions: civic rights connected to individual freedoms, political rights such as voting and engaging in the political process, and social rights which are recognized as our collective social, economic, and cultural rights. Marshall imagined an active and participatory citizenry. Yet in Canada, voter participation had been consistently low since 1993. Voting had become increasingly disengaged from other expressions of civic engagement. Apathy, scepticism and feelings of disempowerment shone through the consistently low voter percentage. Then 2015 happened.

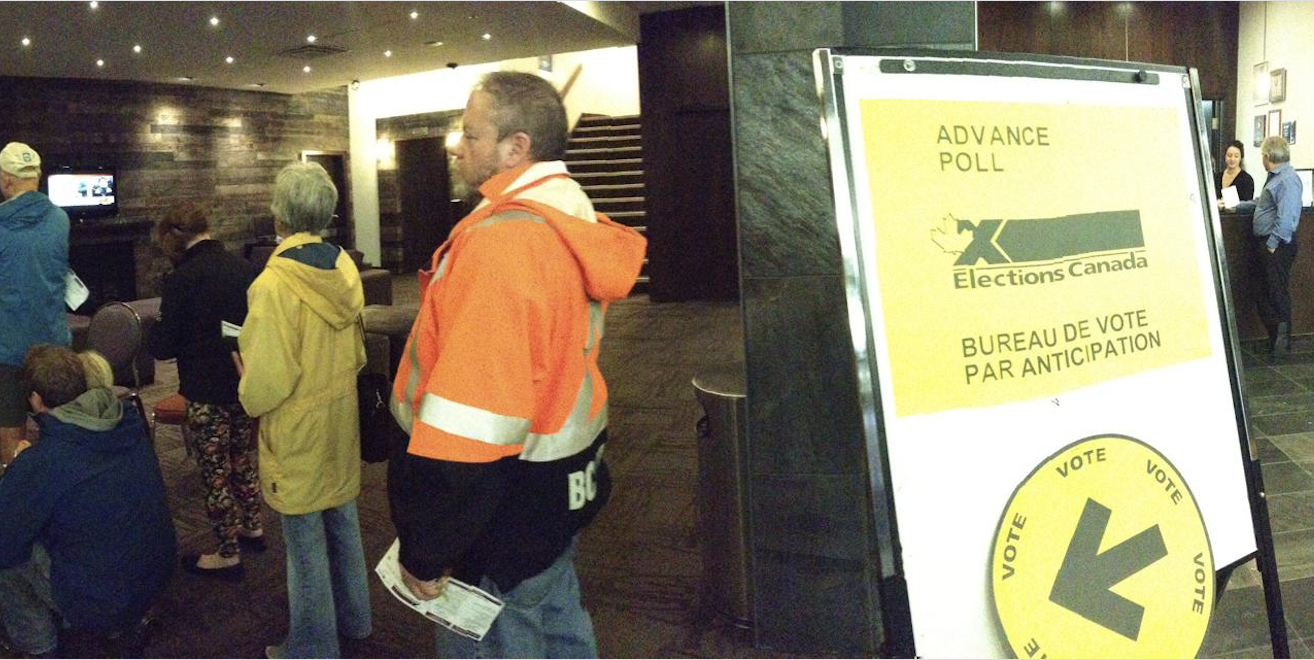

The 2015 Federal Election witnessed the highest voter turnout in over 20 years; there was a point to voting and that point was to take collective action to vote Harper and the Conservatives out of office. According to Elections Canada, historically disengaged or marginalized groups came out strong. From 2011 to 2015, the youth vote (those under 35) increased by an average of 11 per cent, Indigenous peoples — who have over and again experienced the deep and embedded systemic racism that embodies the Canadian state, not even receiving the vote until 1960, came out in droves in 2015. There was an increase in voter turnout of over 14 per cent on Reserves, with Alberta showing an increase of over 25 per cent. Presumably these numbers would be even higher if polling stations had not run out of ballots. According to a StatsCan LFS survey, the immigrant vote also spiked dramatically, over 14 per cent for those Citizens who had been in Canada under 10 years and a more modest 5 per cent for those with more than 10 years of residency.

Social media tools made it possible to organize a social movement focused on voting Harper out of office. The project revived the political arena with a renewed sense of active and participatory citizenship. When voting is part and parcel of a collective action — a defacto social movement defined by collective goals, actions and thinking, emerges and supersedes individual actions, opening the door to dramatic challenges to power.

Specifically, Twitter conversations provide a great example of how social media helped create an online anti-Harper social movement. The Twitter #hashtag journey through the 2015 federal elections helps identify three key strategies for building a successful electoral online social movement: responding to real-time events, initiating advocacy beyond party lines, and encouraging collective action (voting).

As Twitter is my witness: A historical record of missteps and responses

Right from the onset of the election campaign, Twitter facilitated multiple public conversations on everything occurring over its course. Practically every Conservative misstep was documented through #hashtags enabling Canadians — whether they were activists or not — to join the public conversation, to poke fun, advocate and ultimately push a different agenda.

When Harper created an odd video proclaiming no tax on Netflix at the beginning of the campaign, Twitter responded with #HarperANetflixShow posting gems such as “Canadian Horror Story,” “Honey I Shrunk the Democracy,” “Better Robocall Saul,” “Orange is the New Government,” and countless others.

And there was #HairGate (mocking Conservatives for mocking Trudeau) and #PeeGate (Con Candidate, Cup, & Camera), #AngryTory and the appeal to #OldStockCanadians and Canada’s response to #BarbaricCulturalPractices with #ReportYourNeighbour. There was #HarperAGameShow, #HarperScoutBadges and #HarperBlamesAlbertans when he blamed Albertans for electing a NDP government. Every move Harper made was met with a public critique that people engaged in exponentially.

Together we are stronger: Initiating advocacy beyond party lines

During elections, advocacy is often focused on getting a candidate or party into power. Discourse that brings elections and social movements together primarily explores how social movements can help win elections by participating in specific campaigns or backing a specific candidate. But in 2015, Canadians weren’t so much about working together to support someone as they were working to oust someone, thus enabling the movement to grow outside of party lines.

Moreover, what happened outside those party lines went beyond reacting to current events to specific advocacy and organizing initiatives taken on by activists focussed on change. For example, a civil servant suspended for singing rose to instant fame across the country through his protest song, #HarperMan, which rallied people nation-wide and encouraged community sing-alongs to challenge the Harper agenda. #Ottawapiskat, a hashtag challenge to Harper alluding to financial mismanagement on reserves at the height of the Idle No More resistance was revived and turned back on to the Conservative government quickly and deftly.

In addition, while there are well known #hashtags for political conversations in Canada such as #cdnpoli and for 2015 — #elxn42 which demonstrate a vibrant digital public sphere, Canadians also created a number of #hashtags to expose Harper, some of which started during the 2011 Campaign. There was #StopHarper, #LeaveSteve and #HeaveSteve, #StevilHarper and others. Some Canadians even got creative offering #NudesForVotes and yes, let us not forget #HarperDildos too.

Voting is my jam man! From private ballot to public act of defiance

Encouraging voting was a large focus of the #hashtag conversations. #YouthVote, #RockTheIndigenousVote, #IWillVote2015, #RockTheVote and #IVoted, all encouraged people to vote but more so, the conversation as a whole really led voters to cast a ballot as part of a collective action.

By disrupting the individualized electoral space and the sense of disenfranchisement amongst so many, a new collective consciousness was built.

Even when alone — posting a Tweet sitting on the couch, poking fun at Harper, posting their #IVoted selfie or creating a funny video, for the most part my research indicates that people felt they were part of something larger — a collective movement. There was camaraderie, encouragement and a sense of the collective that shifted to the ballot box. Indeed a rich social movement of resistance and opposition and change was built on Twitter that moved the individual act of voting to a collective space by 2015.

So hey, PEI, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, B.C. NWT, and Yukon activists! Get your #Hashtag juices flowing! Let’s make elections not only sites of struggle but also definitive sites of change where we build social movements and we use our collective power for change. The people together are always stronger.

Rusa Jeremic is a professor in the Community Worker Program at George Brown College. Rusa’s PhD dissertation focuses on digital activism and social movement building during the Harper Regime. Her satirical activist alter ego, Miss Ruby Jones a.k.a HarperGirl dedicated many years to exposing Conservative Government policies and practices under Stephen Harper and ousting him from power.