Literature has often described the student-teacher relationship as an electrifying affair, a misunderstood romance, and even a rite of passage.

The trope takes place across genres and forms, in coming-of-age stories, paperback erotica, and young adult fiction. It usually involves a young female student with an older male professor. It’s possible to reverse the relationship or make it same-sex, but the pattern that usually presents itself in literature is a bright, ambitious, and extremely beautiful young woman becoming interested in her instructor. They flirt until the tension is too much to bear, sending them into a passionate and secret affair where he risks his career, reputation, and often his marriage to be with her. He is usually framed as helpless, hopeless, or downright pathetic for her affections.

We’re supposed to believe he’s too pitiful to be predatory.

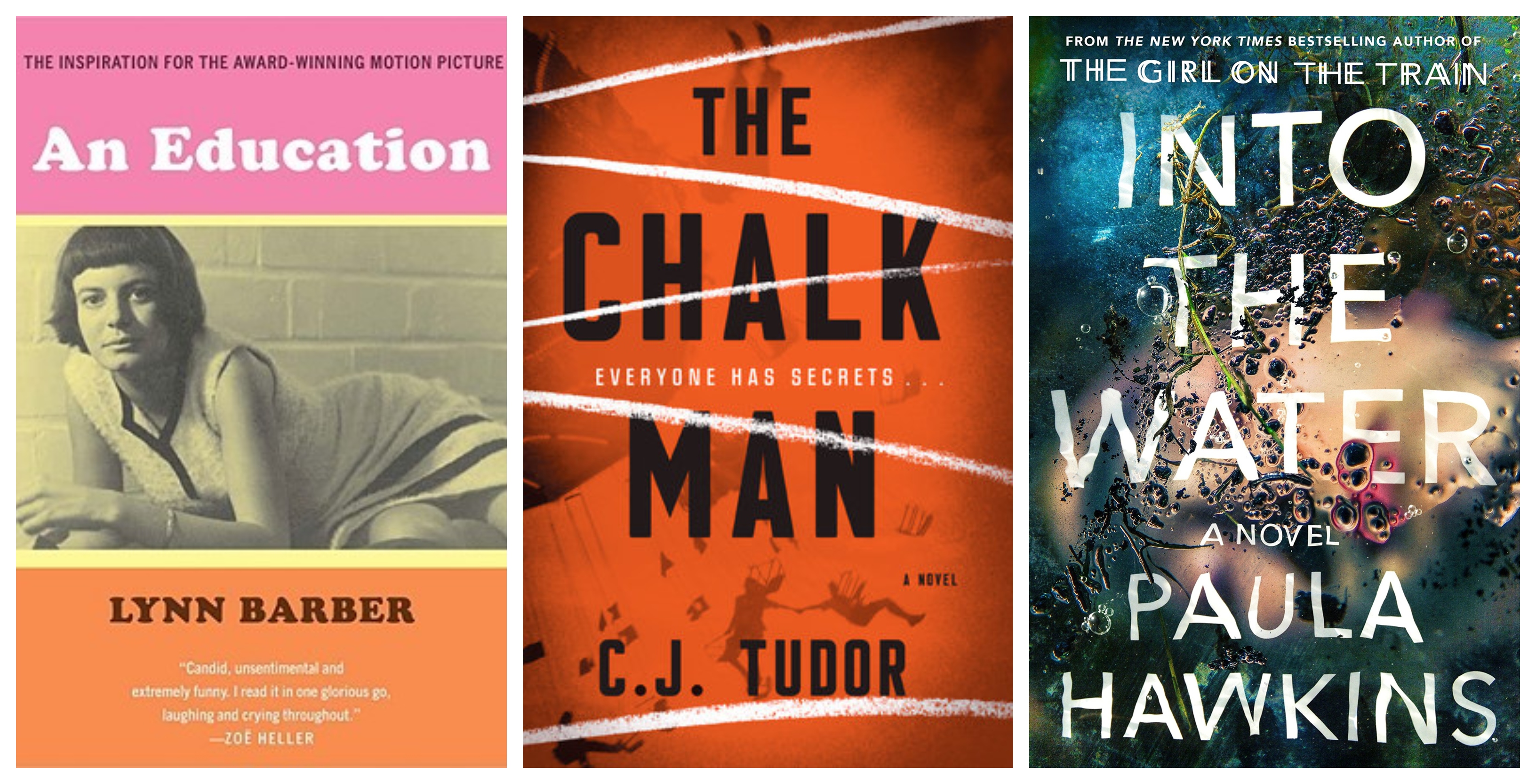

In C.J. Tudor’s thriller The Chalk Man, the teacher Mr. Halloran is made to resign from school after his relationship with a 17-year-old girl (Elisa) comes to light. The young narrator Eddie describes the community being outraged by this news, spreading rumours about Mr. Halloran’s perversion. Eddie frames it as if the parents and children are painting Mr. Halloran with the wrong brush. Mr. Halloran explains to Eddie that the relationship wasn’t salacious. He had fallen in love.

“Elisa is a very special girl, Eddie. I didn’t mean for this to happen. I just wanted to help her, to be a friend.”

“So why couldn’t you just be her friend?”

“When you’re older, you’ll understand better. We can’t choose who we fall in love with, who will make us happy.”

But he didn’t look happy. Not like people in love were supposed to. He looked sad and sort of lost.

Soon after, Elisa’s body is found in the forest. The cops suspect that Mr. Halloran murdered her, and he commits suicide. Similarly, in Paula Hawkins’s small-town mystery Into The Water, 15-year-old Katie is believed to have jumped to her death into the town’s famed Drowning Pool. It’s eventually revealed that one of the high school teachers, Mark Henderson, was having a secret relationship with her. When confronted by her best friend Lena, he vehemently defends his affections as genuine. The heartbreak causes him to unravel and act wildly, going as far as to kidnap Lena.

Over and over, it’s the emotional torture of the teacher the reader sees.

Even when an author tries to describe a teacher who crossed the line and committed an act of sexual predation, readers are tempted to see the good in them. In an interview in Room with Rachel Thompson, author Zoe Whittall describes fans hoping that George from her novel The Best Kind of People was unfairly accused:

There are so many older women and men who just want to empathize with George, and his “plight,” which is dizzying to me. You can’t ever control how your narrative is read, but I truly find it odd that anyone would get to the end of the book and still relate to him or feel for him. He’s so clearly guilty, and I make that clear in the book, yet readers still want to believe that isn’t true.

The common trope encourages readers to believe in the teacher’s goodness or, at least, their pitifulness. When an author presents a less compassionate point of view, it is met with resistance.

The defenses for these imaginary characters are strikingly similar to the responses that people have to real stories of sexual misconduct in school settings. You can see this in comment sections of news articles, where people brush the blame away from teachers and claim that the students actually wanted the relationships. At times, they point fingers of anger and shame at the students over their superiors.

Under the story about Alexandria Vera, a 25-year-old middle school teacher who faced jail time for manipulating and sexually abusing a 13-year-old boy, was one comment that read, “Defrock this mad old judge and throw out the case. What a complete and utter nonsense. People being punished for having fun — medieval.”

A Washington Post story about the pervasive history of sexual abuse at a Maryland private school during the ’60s and ’70s drew this response: “In this case, the women, possibly with the exception of one, voluntarily chose to engage in sexual relations. Even these accusers do not insinuate that their ‘family, friends, dog’ were threatened. They had sexual relations at the time because they enjoyed it on some level. However, now they regret it.”

The reactions get worse as the students get older. University professors, assistants, and instructors are not seen as predatory because their students are over the age of 18. Under another Washington Post piece about academia’s #MeToo movement and how women are coming forward about sexual misconduct enacted by professors, there were comments like: “All it takes is one false accusation from women [sic] who has a grudge against you and your career is finished. There is no due process. I would never see a women [sic] in my office with just the two of us anymore.”

Scholars receive support from more powerful forces than comment sections and Twitter feeds. They are backed by the academic community, industry figures, and the media. When it comes to the notorious University of British Columbia case, the professor in question had many of Canada’s most successful writers come to his defense in an open letter calling the accusations unsubstantiated.

Avital Ronell, a professor of German and Comparative Literature at New York University, was recently accused of repeated sexual harassment of a former graduate student. An internal investigation resulted in her being suspended for the next academic year. Prominent scholars like Judith Butler and Slavoj Žižek sent a letter to the university to defend Ronell. A segment of the letter reads:

We wish to communicate first in the clearest terms our profound an [sic] enduring admiration for Professor Ronell whose mentorship of students has been no less than remarkable over many years. We deplore the damage that this legal proceeding causes her, and seek to register in clear terms our objection to any judgment against her. We hold that the allegations against her do not constitute actual evidence, but rather support the view that malicious intention has animated and sustained this legal nightmare.

The scenario is all too familiar to anyone who has followed UBC Accountable. The letter signed by Butler and Žižek describes the allegations as untrue and malicious, and the legal proceedings as unfair and harmful to Ronell. In their world, it’s the professor who’s the real victim.

It’s easy to fall for the idea of a student-teacher relationship. It feels special that someone with that much influence and experience would pick you. Just like the students in those stories, you were interesting, attractive or unique enough to sway them. You compel them to cross boundaries. This fantasy tries to convince you that the student has control over their teacher, when in reality, the teacher always wields the power.

When the student is a teenager or preteen, the age gap is a major component of the power dynamic. The divide in age and experience makes any romantic or sexual interaction non-consensual in nature, which is why staff members who violate this are often fired and charged with criminal offenses.

What is more difficult to accept is that the power dynamic between student and teacher is not equal when they are both adults. In university, the influence of a professor can be far-reaching, helping your academic career flourish or trampling it before it starts. A lover should not be able to give you failing marks, end positions, or blacklist you from an industry if you displease them. A romantic partner should not be able to dangle career opportunities in front of your face and yank them away at a whim. These are not hypothetical scenarios or exaggerations. There are countless stories of scholars using the promise of success as a reward for accepting their advances, and the threat of punishment for refusing them.

It’s the beginning of the fall semester and hallways are filled with students making their way to and from class. There are staff members who look at these new faces and see potential dates, lovers, or prey. We may not be able to prevent these relationships from ever happening, but we can stop encouraging them, dismissing them, or romanticizing them, either in our fiction or in our everyday lives.

Dana Ewachow is a copywriter working in Toronto. She is a regular contributor to the literary blog The Town Crier.

This piece originally appeared on The Town Crier.

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!