In 1933, Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda chief, spoke at a Geneva conference. His words left the 100 delegates aghast and scared.

“Gentleman, a man’s home is his castle. We are a sovereign state. We will do want we want with our socialists, our pacifists and our Jews and we are not subject to any control whether from mankind in general or the League of Nations in particular.”

The League of Nations had been established after the First World War to promote cooperation amongst nations. One of its two wings was the International Labour Organization which was seen by the Nazis as just another international agency hindering Germany’s national aspirations. The ILO was on the Nazi hit list. So by 1940, when Switzerland was surrounded by German troops and facing a possible invasion, the ILO’s leaders were concerned about the organization’s existence. They asked to set up a centre of activity in the U.S., but were refused.

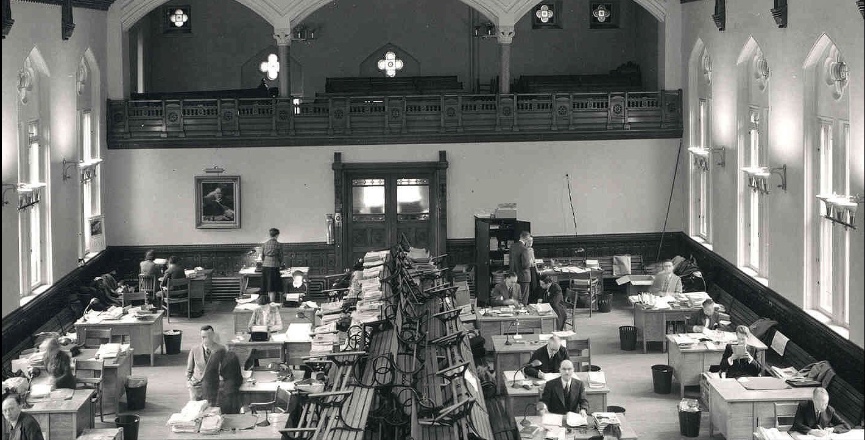

That’s when McGill University stepped in. In 1940, it offered the organization space in a disused chapel and, after a perilous journey through occupied Europe, a core group of ILO officials settled in. The ILO became the only agency of the league to survive and now, in 2019, it is celebrating its 100th anniversary.

The ILO became the first specialized agency of the United Nations when it was created in 1945. It adopted a constitution which emphasized social justice and reiterated its guiding principle, taken from the Treaty of Versailles, “…that labour should not be regarded merely as a commodity or article of commerce.” Workers are not objects to be bought and sold on the market.

Today the ILO includes 187 of the UN’s 193 states. Its primary task is to promote minimal labour standards for the world’s 3.5 billion labour force. It does this by creating international treaties called conventions which can be adopted by member states. Once adopted a convention becomes part of the country’s legal infrastructure. The organization also produces non-binding recommendations and provides technical assistance to help countries create Decent Work programs.

The ILO is operated as a tripartite organization with representatives of governments, employers and labour unions. Its director general is Guy Ryder, the first trade unionist to lead the organization. The labour union section of the ILO is the Bureau for Workers’ Activities which operates under its French acronym ACTRAV. Canadian delegates attending the ILO’s annual conference are nominated by the federal government, the Canadian Employers Council and the Canadian Labour Congress. The organization is holding its 108th conference in Geneva from June 10-21, 2019.

In 1969, 50 years after it was founded, the ILO won the Nobel Peace Prize.

The ILO has eight fundamental conventions which member states are expected to adopt. They cover topics such as freedom of association (the right to form a union), collective bargaining, the abolition of child labour and the eradication of discrimination at work.

For years Canada refused to ratify all the core conventions. But the current Liberal administration moved quickly to remedy that. In 2016, it ratified the Minimum Age Convention. In 2017, it ratified the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, C-98.

Ratification of an ILO convention has profound legal implications. In 2007, the Supreme Court ruled that Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms should be interpreted in light of the country’s international treaties while it affirmed the right to collective bargaining. In 2015, the court ruled that the right to strike is protected by ILO Convention 87 on Freedom of Association. In 2016 it restored essential bargaining rights to BC teachers citing an ILO ruling in favour of the B.C. Teachers Federation.

The most recent affirmation of the ILO’s importance for Canadian workers came with the signing of the USMCA trade agreement in September 2018. Under its predecessor NAFTA, labour conditions were relegated to a side agreement. However, in the USMCA agreement labour provisions are included in the body of the agreement and can be adjudicated by the state-to-state procedure. USMCA Chapter 23 explicitly cites the ILO’s 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work as a basis for its provisions. The declaration affirms the eight core conventions covering unionization, collective bargaining and other issues.

But as important as the ILO has become for workers in Canada there is much more to be done. Unions in Canada are lobbying for the adoption of conventions on domestic workers (C-189), migrant workers (C-143), Indigenous people (C-169) and the proposed Convention on Violence Against Women at Work.

If there is one thing you should remember about the ILO it is this: there is no way that a multinational treaty organization which has labour unions as part of the top leadership would ever be created today. We need to not only celebrate the ILO’s survival over the past 100 years, but make sure that it exists for many more years to come.

Marc Bélanger is the news producer at RadioLabour — the international labour movement’s radio service. He is a former head of the ILO’s Labour Education program in Turin, Italy.