In the prelude to the 2015 federal election, NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair is talking job creation in southwestern Ontario.

He’s promising more small business tax cuts and credits as his entry point. It’s the political norm these days to promote low business taxes, but the reality is small business tax cuts are already old hat. Here’s why:

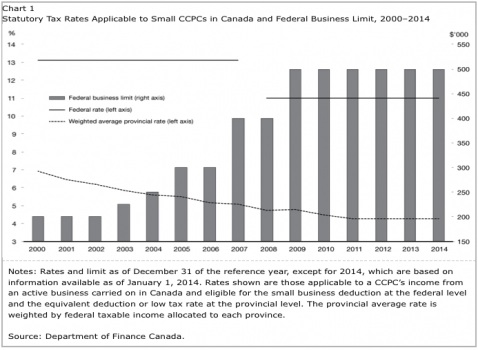

About a year ago, Canada’s Department of Finance released a report outlining the changes in effective tax rates for small businesses, or Canadian controlled private corporations (CCPCs) as they are called in tax language, between 2000 and 2011.

The verdict: taxes paid by small businesses, at both the federal and provincial level, have decreased dramatically since 2000: a small business with $500,000 in taxable income pays less than half the combined federal and weighted average provincial corporate income tax it paid just 13 years ago. (Provincial tax savings are calculated based on the weighted average provincial small business tax rate and the federal business limit.)

That’s right, small businesses in Canada now contribute less than half in taxes than they did at the turn of the century.

This dramatic decrease is the result of two changes.

First, the business limit — the ceiling on the corporate income eligible for the small business deduction — has increased from $200,000 in 2000 to $500,000 in 2009. As a result, higher earning businesses, and more of them, are eligible for the small business deduction than was the case in 2000.

Second, the increase in this ceiling has been accompanied by decreases in the tax rate applied to small businesses. Across Canada, the weighted average provincial and territorial tax rate applied to small businesses has decreased from 6.9 per cent in 2000 to 4.3 per cent by January 1, 2014.

The federal small business tax rate currently sits at 11 per cent; it was 13 per cent in 2000.

During that same time period, Ontario’s small business tax rate dropped from 7 per cent to 4.5 per cent. B.C.’s dropped from 5.13 per cent to 2.5 per cent. Saskatchewan from 8 per cent to 2 per cent. Over the 13-year period, Manitoba’s small businesses went from paying a 7 per cent provincial tax rate to paying nothing at all at the provincial level.

And it doesn’t stop there: the federal New Democrats want to lower the small business tax rate even further — to 10 per cent immediately and to 9 per cent as soon as finances permit.

It’s a promise that echoes one made during last year’s Ontario election when the provincial NDP vowed to lower the small business tax from 4 per cent to 3 per cent if they were elected (they weren’t). I wrote about the ill-advised nature of that political promise back during the spring 2014 provincial election.

What is the combined effect of this race to the bottom for small business and corporate taxes?

Small business tax cuts are promoted as an incentive for small businesses to reinvest their earnings and create jobs. The data suggest it’s a dubious claim.

Data from Statistics Canada* reveal that between 2000 and 2013 the number of incorporated self-employed individuals in Ontario increased by more than 40 per cent. That means incorporated self-employment now makes up 43 per cent of all self-employed individuals in the country. Furthermore, the share of self-employed individuals with no employees has increased from 12 per cent to 20 per cent over the same time period.

Construction, professional, scientific and technical services, finance, insurance, real estate, and health care, and social assistance make up a significant portion of this change, representing more than 50 per cent of all incorporated small businesses with no employees.

It appears the combination of business tax changes are inducing self-employed, high-income earners — such as doctors, lawyers, accountants, and small consultancies — to incorporate and take advantage of lower tax rates.

As Hugh Mackenzie pointed out in a recent blog post: They’re not what one typically imagines when one thinks of a small business. But these small business owners face a marginal tax rate that is much lower than the top federal-provincial marginal income tax rate that is paid by people who are wage earners. This difference makes it attractive to incorporate for tax planning purposes. It provides a way for high-earning individuals and families to reduce their taxes as well as their contribution to public services that build equity and fairness into the economy.

This tax policy is one among many factors contributing to income and wealth inequality in Canada. It is also undermining fiscal health and the government’s ability to pay for the services Canadians benefit from.

And, after 14 years of the same old pattern, it is worth noting that more could be achieved through investing in public services than can be achieved through tax cuts that don’t deliver their intended results.

* Statistics Canada. Table 282-0011 — Labour force survey estimates (LFS), employment by class of worker, North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) and sex, unadjusted for seasonality, annual (persons). Accessed: March 4, 2014.

Kaylie Tiessen is an economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Ontario Office. Follow her on Twitter: @KaylieTiessen

Image: Flickr/dumfstar