Environmental activists, climate justice organizers and Indigenous people are preparing the Defend Our Coast rally on Monday (Oct. 22) in Victoria, B.C. But as people voice their opposition to oil sands, pipelines and tankers on the coast, why have decades of struggle to protect the Earth not succeeded in changing the growth-based economy?

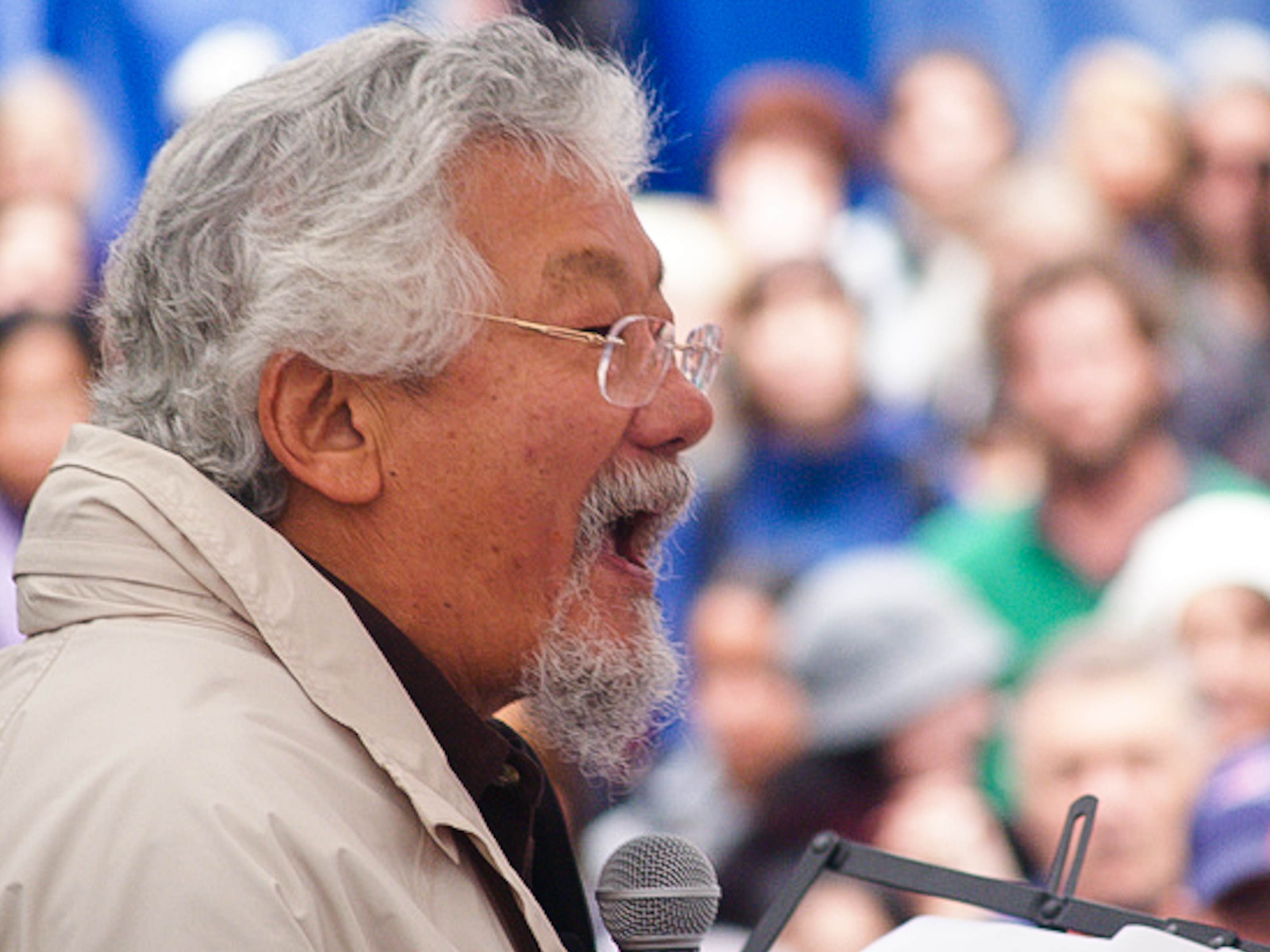

The Left Coast Post brings you a conversation between renowned broadcaster and scientist David Suzuki, and Media Mornings on Vancouver Co-op Radio – hosted by David P. Ball and Anushka Nagji.

Is capitalism compatible with environmental reform? How do we achieve a “paradigm shift”?

Listen to the Media Mornings show featuring this interview, plus information on Monday’s protest and an interview with Greenpeace co-founder Rex Weyler. Here is a transcript:

DAVID P. BALL: This Monday, there’s a big environmental action in Victoria organized by many environmental groups – kind of modelled after the Keystone protests in Texas and around the White House, Canada’s contribution if you will. What is your take on whether the issues joining tankers, pipelines and climate change can move the public to take action on these things?

DAVID SUZUKI: The polls have indicated that British Columbians, certainly overwhelmingly, do not support the idea of the Northern Gateway pipeline or tankers going along our coast. We’ve had a moratorium on tankers for 30 years – that’s because British Columbians recognize very clearly the threat that this poses to our coast, that we value very much.

DB: One thing I was hoping to talk with you about today, for our listeners, is to look beyond the individual pipelines – you knock one down, but another just seems to pop up. It seems […] the economy itself is structured to increase consumption. We have this ideology of endless growth. What is your take on that? What needs to be done about it?

DS: The reality is the environmental movement, despite its enormous success in the first 30 years of its existence after 1962, has been failing miserably in the last 20 years. Battles that we fought 30 to 35 years ago are now coming back — we’re fighting the same battles. We stopped supertankers along the coast of B.C. We stopped the proposal to drill for oil in the Hecate Strait. We stopped a dam proposed at Site C on the Peace River. We stopped a dam at Altamira in Brazil. But all these issues are coming back, which means we haven’t shifted the way that we see the world around us.

I hope that perhaps the tar sands issue now will let us look at the bigger picture, which is that we face a major crisis with the atmosphere, and we can’t have an economy that is based on constant, endless growth. I’m touring right now across Canada with an economist – he used to be the senior economist with the CIBC, Jeff Rubin – who has just published a book called ‘The End of Growth.’ To have an economist now echoing what the Club of Rome wrote years ago – ‘Limits to Growth‘ – to have an economist saying the economy cannot grow indefinitely – it’s coming to an end – is a very important moment for us to sit down and say, “Where the hell are we going? How do we design a truly sustainable future?”

ANUSHKA NAGJI: So where can this dialogue happen? We’re trying to not go back and reconsider the issue again and again of climate change and the pipelines. What are the underlying narratives that we can access? We’re talking about Indigenous self-determination, and other issues that come up with these pipelines.

DS: The thing that British Columbians should be very grateful for is the 100 per cent opposition of coastal First Nations to these pipelines. We should be grateful that they’re raising this issue. I’ve gone into every one of the communities along the coast – they’re desperate for jobs; they’re desperate for economic development. And yet, despite the offers of millions of dollars from Enbridge, they are 100 per cent opposed to the pipeline in their territory. Why? They’re telling us there are things more important than money. They’re telling us that culture, history and the future are all tied up in the threat from the supertankers that will come through. We have to be listening to that. These communities want jobs, they want economic development, and yet they are telling us, ‘Look at what really matters in our lives.’ And I thank them for that.

DB: You’ve touched on what you call a failure or challenge that environmentalism has had over the years. In fact, in May you published ‘The Fundamental Failure of Environmentalism‘ as a column. In there, you speak very clearly about the economic system, in particular the financial crisis. I want to quote from that:

“Aided by recessions, popped financial bubbles, and tens of millions of dollars from corporations and wealthy neoconservatives to support a cacophony of denial from rightwing pundits and think tanks, environmental protection came to be portrayed as an impediment to economic expansion.”

Could you talk a bit about that? Those are some very uncompromising words.

DS: Well, I mean, that says it all! Our current government has had an omnibus bill in which they’ve undermined 50 years of hard-won legislation to protect the environment, because it’s seen as an impediment to the development of the tar sands and other things like mining and fracking – all of these economic “opportunities” – are now being pushed. And environmental legislation is seen, really, as a pain in the neck.

AN: Going back to the civil disobedience action happening on Monday, is that a chance to start calling the government out on these sorts of things? What happens next?

DS: To get a large number people on the lawns of the Legislature to raise these issues – civil disobedience is simply one of those things about attracting attention. The number of people that are going to be there – really demanding a deeper discussion about our energy future, about our economic system – that’s the important thing.

We need something like the Quebecois had, for weeks and weeks, when they had tens of thousands of people, night after night, demonstrating. Those are learning moments when we can raise these other issues. The problem is the political agenda is driven by a very, very short-term vision – it’s about the next election. The corporate agenda is all about profits and quarterly reports. But no one’s looking ahead and asking the question, “Where the hell are we going?”

AN: The Legislature’s not in session on Monday. So we’re all getting together in Victoria, [but] what’s the civil disobedience part of this – where does that go?

DS: I don’t know […]. I signed the letter because I think we should be ready to put our bodies on the line if it’s imperative to really make a demonstration about how urgently we feel about this. We’ve got to be ready to put our bodies on the line.

DB: […] In the same column, you talked about of a “paradigm shift.” I know people have been talking about this for decades. You even mention economists like Jeff Rubin – I just saw him being read on the bus this morning, coming in here at 6 a.m. Why isn’t that taking root within the capitalist system? It seems like the actual system itself may be including some externalities – what they call environmental externalities – and they all have corporate social responsibility [policies]. But, at root, it’s still about growth. How do we shift that paradigm?

DS: The problem is the way we see our place in the world is what shapes the way we act. If you look at our history as a species, for 95 per cent of our existence, we were nomadic hunter-gatherers. And as a hunter-gatherer, you know damn well that you’re absolutely embedded in, and utterly dependent on, nature for your survival and well-being. 10,000 years ago – the last five per cent of our existence – we discovered agriculture; if you’re a farmer, you know very well that the seasons, weather, climate directly affect your ability to survive or not. They know that winter snow is directly related to how much moisture you have in the soil in the summer; that insects – yes, some are pests – but they’re absolutely crucial for pollinating flowering plants; that certain trees and plant species can take nitrogen and fix it as fertilizer in the soil. Farmers know that we are part of nature.

What’s happened is a fundamental shift in the last 100 years that now blinds us from being able to see our place on the planet. 85 per cent of us in Canada now live in big cities. We’ve been utterly transformed in 100 years from being a farming animal to a big city dweller. And in the big city, people think, “As long as we have parks out there, where we can go camping and playing in, well who needs nature? My important thing is my job; I need a job in order to be able to go out and buy the things I want.”

So, from an urban perspective, then, the economy becomes the source of everything that matters to us. And when you’re living in that world – where the economy is elevated above everything else – then of course you’ll say, “We can’t stop clear-cutting – it’ll destroy the economy. We can’t stop dragging huge nets across the bottom of the ocean, because it’s bad for the fisheries. And we can’t stop injecting carbon into the atmosphere, because that’ll shut down the fossil fuel industry.” The economy, then, trumps everything else because that’s our highest priority in the city. It becomes very, very difficult to see the real world. And it’s becoming increasingly more difficult as children spend less and less time outside.

DB: As a final question, Dr. Suzuki, could you reflect on the importance of independent media – not just community radio stations, but places like DeSmogBlog, the Vancouver Observer and the Tyee? These places seem to be offering some of the few refuges in a world with a narrowing discourse, where economics seems to trump all.

DS: You have concentration of power and control in the media. Even the CBC, our national broadcaster, is now heavily dependent on advertizing. That shifts, then, the kind of reporting and way you present things. We, at The Nature of Things, argued against ads for years and years. When they came in, we knew it would influence the way that we present stories. So far, thank goodness, we haven’t actually been censored. But you can bet that our programs are heavily vetted by lawyers, who are constantly worried about whether we’ll get sued and all that stuff.

The media become, in a way, hostages of the corporate agenda. Thank God for the independents like you and like the various blog sites – but again, when you look at social media, it’s just awash in garbage. The problem now is, if you want to believe that climate change is junk science, well guess what? You go on the internet, there are dozens of blog sites that say just that: that this is a conspiracy of scientists to get more money, that this is a natural cycle. The skeptics are all out there, and it becomes very, very difficult for people to manoeuvre their way through this stuff, which of course is being heavily funded by vested interests.