Let me explain B.C.’s strategy for addressing discrimination. First, we ask someone to experience it. Then we ask that person to understand a complex area of law, investigate the facts and engage in a legal proceeding against their employer/landlord/service provider to enforce their rights. We ask many people to do this without any legal help.

What would it look like if we actually acted proactively to try to avoid discrimination in the first place? Just ask the other nine provinces, which have invested in a proactive system for exposing, understanding and preventing discrimination. All of Canada’s provinces, except for B.C., have a Human Rights Commission.

B.C.’s lack of a Human Rights Commission matters.

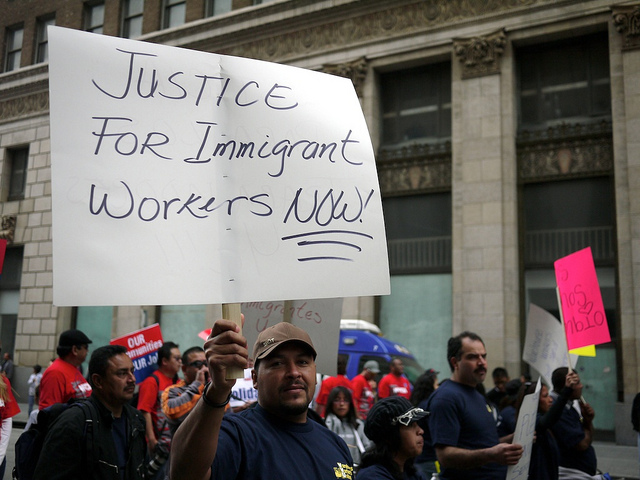

I’m a non-profit lawyer who represents and advises low-wage workers about their human rights in the workplace. Over the last year, I’ve had a growing number of calls from a group of uniquely vulnerable workers in our province: temporary foreign workers. I have received enough calls, and read enough media stories, to say confidently that these workers experience discrimination as a predictable by-product of their legislated working conditions. They are vulnerable to discrimination on a systemic level.

Most people think it’s daunting to sue their employer. But few of us can understand how truly formidable that proposition becomes when a person is reliant on their employer not only for their job, but also their immigration status, housing, and long-term prospects of being reunited with their family. The obstacles faced by temporary foreign workers to enforce their basic human right to be treated with dignity in the workplace cannot be understated. In my experience, it is the rare worker indeed who can bear this burden.

Also in my experience, the odds are that when discrimination is happening to one temporary foreign worker in the workplace, it is happening to a group of workers. This could include racial or sexual harassment, or breaching minimum standards of employment like failing to pay minimum wage. Again, this is a systemic form of discrimination.

Asking these workers to shoulder the responsibility of understanding, investigating and exposing the ways in which they are being abused, and providing the complex evidence necessary to tie their exploitation to factors like their race or gender, is too much. It ensures that systemic discrimination against temporary foreign workers remains hidden and poorly understood. It ensures that systemic discrimination against temporary foreign workers will continue.

A Human Rights Commission has the mandate to investigate and understand this type of systemic discrimination. It can create guidelines for employers to understand their obligations and workers to understand their rights. It can educate the parties, the government and the public about what makes temporary foreign workers vulnerable and what kind of treatment will be unlawful. It can help us to prevent this predictable but unacceptable discrimination.

It’s time for B.C. to catch up … again. B.C.’s low-wage workers need a Human Rights Commission. The responsibility for fighting discrimination in the workplace cannot be theirs alone.

Devyn Cousineau is a member of the Employment Standards Coalition and a CCPA–BC research associate.

—

This blog post is part of a series on human rights, based on the new report Strengthening Human Rights: Why British Columbia Needs a Human Rights Commission. Find other blogs in the series here.

Photo: Paul Bailey/flickr