It took the mass murder of six Asian women in Atlanta by a 21-year-old white man to draw attention to anti-Asian racism. But this tragedy is the latest in a long-standing history of unrecognized anti-Asian racism, misogyny, and murder across Turtle Island.

U.S. history is fraught with anti-Asian violence dating back 150 years: the mass lynching of 19 Chinese individuals in 1871; the Rock Springs massacre of 28 Chinese people in 1885; the killing of Chinese people who were mistaken for being Japanese. Furthermore, there was the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and the Page Act (1857), which were rooted in the fear of Chinese women being potential sex workers.

The Atlanta murderer claims he isn’t a racist but a sex addict, and yet, he targeted these six Asian women. In fact, it is precisely at this intersection of racism and sexism that the white man’s insolence towards Asian women takes form.

Anti-Asian racism is embedded in U.S. foreign policy designed to terrorize and destabilize Southeast-Asian countries. Blaming China as a threat fuels nativist discrimination against Asians. The true history of Asian Americans is distorted by the media, absent in textbooks, and extravagantly tokenized in Hollywood war films and popular culture.

Inspired by the 1904 opera Madame Butterfly, Schönberg and Boublil’s 1989 Broadway musical Miss Saigon portrays Asian women who would choose white men over Asians, deny themselves happiness, and willingly die for white men.

Scantily clothed Asian women are splashed across the screen in suggestive gestures, underbidding themselves to white soldiers. Submissive and self-sacrificing Asian women are depicted as white men’s loyal romantic partners, fitting the white male-gaze stereotype of what Asian women should be.

A similarly malignant orientalist fantasy is perpetuated in countless Hollywood war films, ranging from The Deer Hunter to We Were Soldiers, alongside numerous TV shows.

The film that personifies this anti-Asian attitude most dangerously is Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 film, Full Metal Jacket, in which a Vietnamese sex worker lures Marines with “me so horny.” It inspired the hip-hop hit by 2 Live Crew, which included the line “me love you long time” — which would fuel the fetishization of subsequent generations of Asian women.

In this film, a teenage Vietnamese girl, a sexual temptation a moment ago, is shot in a gang-type killing by Marines conditioned to march holding rifles and clutching genitals, shaping white male attitudes towards Asian women.

These films liberally portray Vietnamese people as passive sex workers (in a depiction fraught with a double-edged demonization/victimization of sex work), or enemy collaborators — and Vietnamese guerillas as heartless torturers. What is absent in these films is any semblance of actual Asian representation and admission of willful American atrocities.

Broadway and Hollywood’s legacies of fetishization are re-lived on Canadian stages by Quebec’s renowned Robert Lepage in The Dragons’ Trilogy and The Blue Dragon — large-scale Asian-themed productions by a white man, in which the real Asian is absent.

The generational repercussions of Chinese labourers who built the Canadian Pacific Railways, and the Chinese head tax that segregated men from their wives into bachelor communities (which are the precursors of today’s Chinatowns), are entirely overlooked. Instead, Asians are portrayed as a device to tell the stories of white Canadian cousins.

Lepage’s The Seven Streams of River Ota uses Hiroshima as a metaphor for the Holocaust and AIDS, once again told by white men. Asians have a reductive presence, hardly uttering any dialogue, though the productions run for nine hours. While these “Asian plays” commodified Lepage’s global reputation, Asian-Canadian artists struggle to tell their stories in their own voice.

Asians are further subdued through the “model minority” rhetoric, making them desirable, diligent and exotic objects who keep quiet. They serve as a model minority not because of who they are, but because of who they are not: Arab, Muslim or Black.

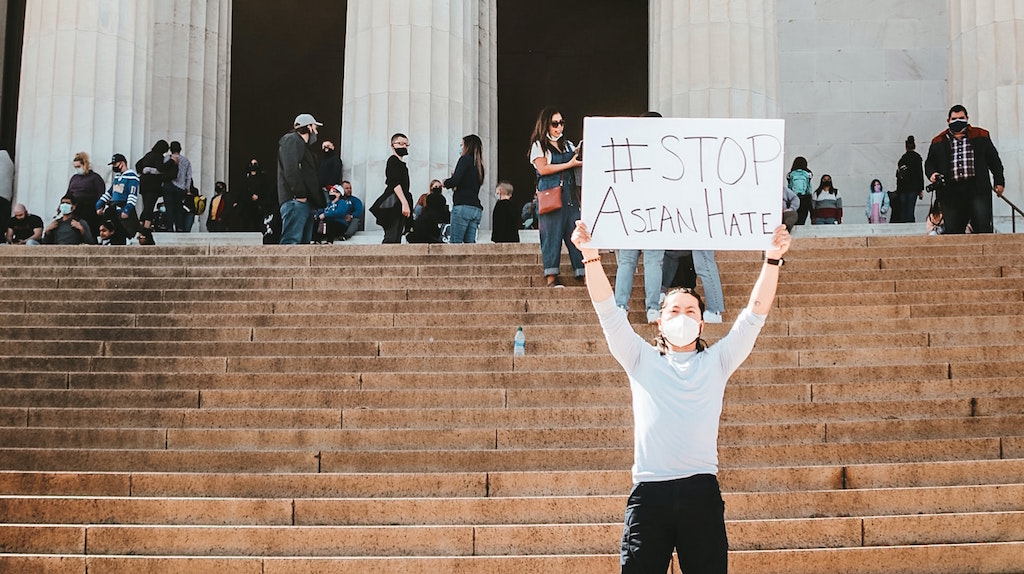

The national conversation about diversity, inclusion and equity has not eliminated racism. The Atlanta mass murder has renewed national attention to racism, and centralizes the country’s urgent discussions on race, colonialism, and culture.

Rahul Varma is artistic director of Teesri Duniya Theatre.

Summer Mahmud is a recent graduate of McGill University’s Department of English Drama and Theatre Studies.

Image credit: Viviana Rishe/Unsplash