Thousands of women (13,000 in Toronto) went out last week, over “pussy” related issues, officially gathered under the Women’s March on Washington label. The March had a global envergure: it took place in many cities around the world on January 21, the day after the inauguration of the new U.S. president, Donald Trump.

Yet only about 3,000 people were confirmed to attend Monday’s morning protest at the United States Consulate in Toronto, against the “Muslim ban” executively put forward by Donald Trump. The “ban” is intended to prevent citizens from seven predominantely Muslim countries (Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, Yemen and Iraq) from entering the wannabe dream-making, soon to be the wall-protected nation of the United States of America, for about 90 days (the number of days formerly allowed under the Visa Waiver Program).

The order seems to not apply to the Muslims states of Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates. We can all guess why. Yet the ban surely applies to dual citizens and residents — those already legally entitled to reside, study or conduct some sort of business in the United States. Or differently said, those legally entitled to belong to the community of value whose borders shape the American nation-state.

Migrants are foreign people entering a nation and subsequently, differentially included into, or excluded from the nation, based on who they constitute as categories of migrants and how they are imagined to fit within these categories and within the nation. We all know by now that within the recent American public rhetoric, refugees per se are not imagined to fit within the great American nation.

On the one hand, the ban will keep out asylum seekers (for about 120 days), as it places a cap on the number of new entries into the country, based on such exclusionary imaginings. On the other hand, it will also politically delineate who has the right to belong and be included into American-ness.

It is one thing to exclude the already-excluded (common praxis within policy making) or to deny entry to the ones not seen as worthy of deserving entrance (not that we should take sine qua non the deserving/non-deserving distinction from the English Elizabethan times), but trying to exclude the ones who have been de facto included (already “legally” allowed into the nation) means that the whole game of granting rights and entitlements gets re-engineered on stringent national and cultural values of belonging, while shifting the very same parameters from which legality and illegality get defined and redefined.

Premeditating expulsion of those seen as unfit to fit in, based on their cultural and/or religious characteristic of being Muslim, and extending the legal sphere over cultural prejudices of belonging and non-belonging, constructs “culture” by excellence as a site where inclusionary and exclusionary processes get to be manifested.

Concerns however, are not only with whom the state views as “illegal” within its shifting parameters of legality but also with finding illegitimate and illegal ways (Trump’s executive order was legally challenged in court by the American Civil Liberties Union) of moving legal subjects in illegality simply because they do not fit our imaginings of belonging to the great exceptional nation that constitutes the United States.

Similar was observed with the Brexit logic. Brexit was the consequential result of protecting national borders and fighting against the rights of free movement within the European Union, hence an effort to definitively exclude immigrants from Britain as a community of value, and to impose Britain as Britain, in relation to everything else.

Comparably, Trump’s “Muslim ban” is more about protecting jus sanguinis Americaness and keeping it away from the Muslims subjects that would culturally pollute it. “To protect our country and keep it safe” could ad litteram be interpreted as the state’s right to outline who is part of America and who should be part of America.

I got to the United States Consulate in Toronto at about 8:30 a.m. on January 30. The police were roaring of course and a helicopter was patrolling above; although, in anticipation of the protest, the Consulate closed its doors for the day. Numbers were difficult to estimate. Around 500, I would say, or perhaps close to 1,000. Still incomparably shorter than a week ago.

While people did gather for impromptu, ongoing protests across the United States, the overall public outcries over the “Muslim ban” did not match in magnitude those over the Women’s March. Sure, some may say, the Women’s March was organized on the election momentum and people had since November to plan and organize the event ahead of time. However, as much as I do believe that life is mostly about timing and moments, I attribute such discrepancy in numbers to ideological reasons.

In writing about violence, Hannah Arendt wrote that “In order to respond reasonably, one must first of all be ‘moved’ and the opposite of emotional is not ‘rational,’ whatever that may mean, but either the inability to be moved, usually a pathological phenomenon, or sentimentality, which is a perversion of feeling”.

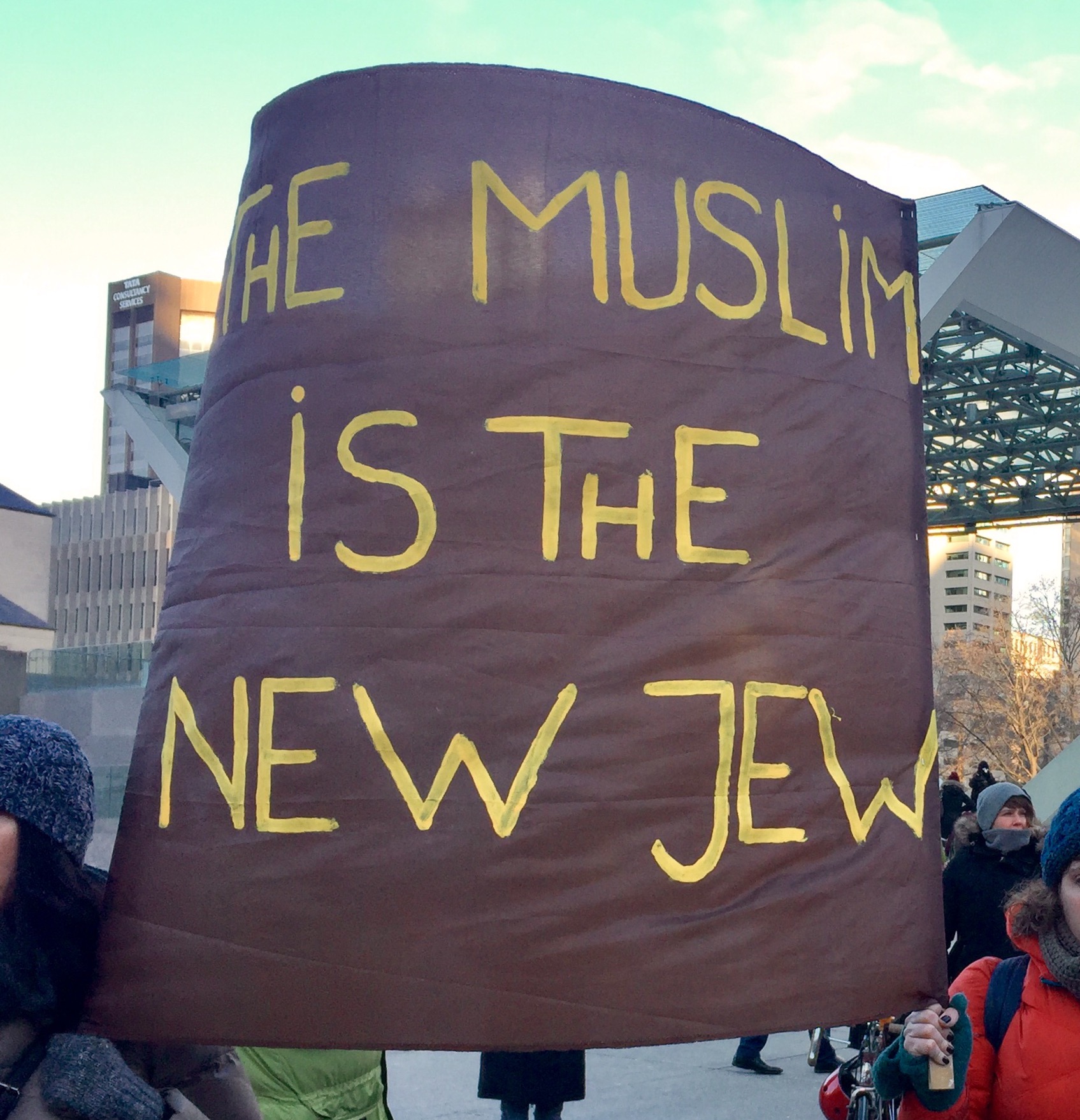

And in terms of values and ideas, the Muslim as the new Jew, does not move us the same way as abstract “pussy” issues do. Because women are better off making their 100k, supplementary buying pink cashmere thread to knit pink pussy hats, and symbolically and diligently marching over abstract, non-institutionalized pussy-grabbing issues. They are better off posting photos of the Marches on Facebook, taking pride on having some Vogue coverage, and continually morning the lost legacy of Obama’s presidency.

All while failing to responsibly acknowledge that Trump’s ban could not have been almost-institutionalized if Obama had not signed initial restrictions on these seven countries in December 2015, right after the Paris attacks, making it harder for their citizens or travelers from within the region to enter the United States.

As angry as we are with Trump, he is only a symptom. A consequence of the hyper-neoliberal, drone-infused system that culminated in the American racist state and the holy blessed land of imperial America.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Photo credit Andreea-Iorga Curpan