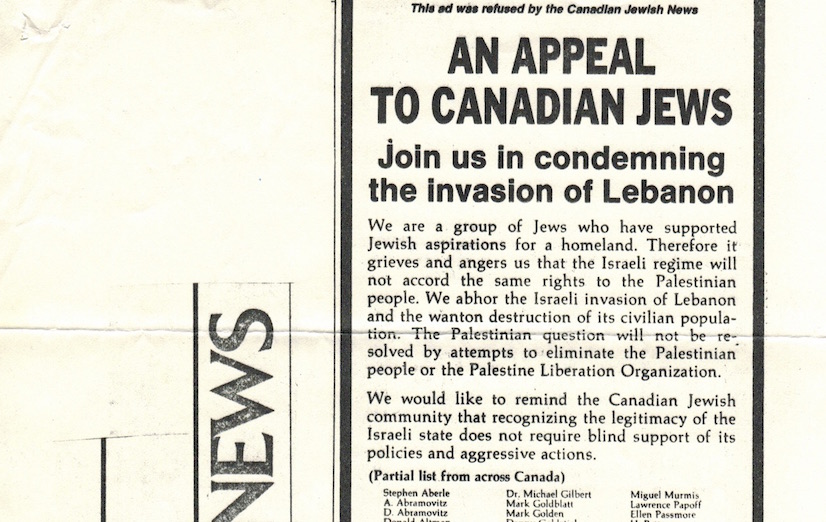

An Appeal to Canadian Jews: Join us in condemning the invasion of Lebanon

We are a group of Jews who have supported Jewish aspirations for a homeland. Therefore, it grieves and angers us that the Israeli regime will not accord the same rights to the Palestinian people. We abhor the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the wanton destruction of its civilian population. The Palestinian question will not be resolved by attempts to eliminate the Palestinian people or the Palestinian Liberation Organization. We would like to remind the Canadian Jewish community that recognizing the legitimacy of the Israeli state does not require blind support of its policies and aggressive actions.

– An August 22, 1982 newspaper ad in the Toronto Star containing about 100 names of Canadian Jews. The Canadian Jewish News refused to carry this appeal, so it was published in the Star instead.

Sometime in the summer of 1982, Jews in their 20s and 30s in Toronto, including myself, came out in droves to meetings of the new Committee of Concerned Canadian Jews (CCCJ). (Yes, our name was a bit awkward and wordy.)

“It brought people, the fence sitters. We were a strong movement. Meetings attended by 50 or more people,” recalls Richard Lee, a University of Toronto professor of anthropology.

One of our first acts was to negotiate among ourselves the appropriate wording for our ad. Among the signatories were writer and journalist Rick Salutin, academic and NDP organizer Gerald Caplan, and dissident Rabbi Reuben Slonim — the latter had been fired by his Toronto synagogue. What stood out about our ad was that it emphasized the plight of the Palestinian people and the efforts to neutralize or kill them instead of coming to terms with their historic claims and grievances.

Any open criticism of Israel was strictly taboo in the tightly knit postwar Canadian Jewish community, which included many refugees and Nazi death camp survivors. Many community members, including my parents, viewed the founding of a Jewish state in 1948 as a miracle and central to their identity and existence, and a place of refuge from antisemitism.

Fissures started to develop following the opportunistic invasion launched by Israeli defence minister Ariel Sharon. Then came the horror of the mid-September massacre of more than 1,300 Palestinian and Lebanese men, women and children in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut. Members of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) stood by as their allied Lebanese Christian Phalangist militia men went about their rampage.

The tough words in our newspaper ad made us a target. One letter compared us to Jews who had collaborated with the Nazis. Ester Reiter, listed as CCCJ chair in the ad, had her own unsettling experience.

“My youngest son, who was 16, was home alone. He got a hate phone call threatening to hurt him. He was so scared and I was away for the weekend. He stayed away from the house at an all-night café for four nights. He was afraid to go home.”

Our second high-profile action was to picket the Israeli consulate on Bloor Street. This upset former Ontario NDP leader Stephen Lewis, who hurled some rhetorical thunderbolts in our direction from the perch of his private radio commentary. Some of this may have been due to the historic ties between the NDP and the Labour Zionists who founded the State of Israel.

Author and historian Erna Paris covered what she called a “trauma” among Jews in Canada over Lebanon, in her April 1983 Quest Magazine article, “Aftermath: Canada’s Jews and the Summer of Lebanon — The Debate is Painful but It Could Bring Canada ‘s Jewish Community Closer Together.”

Paris wrote that in addition to the CCCJ, the other significant dissenting voices in our community with regard to Israel were Rabbi Slonim, Friends of Pioneering Israel (a small socialist Zionist organization) and surprise — Irwin Cotler. Forty years later, the now retired McGill University law professor is Mr. IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance) in Ottawa. (More on that later.)

In 1982, Cotler was more dovish to a certain degree, based on what Paris describes as his “convictions.” In adoring sentences, Paris explained that Cotler was willing to risk censure from his community and his own wife by echoing international calls for an independent inquiry on the part of the Israeli government of Menachem Begin into the Sabra-Shatila massacre: “Cotler is a man passionately concerned with questions of human rights — including Palestinian rights.”

What influence this Canadian had in the eventual decision by the Begin government to hold an independent inquiry is not clear. Suffice it to say that a 1983 report came out and there were resignations inside the Israeli government and military. However, Ariel Sharon’s political career did recover, and Israelis had to wait until 2012 for new documents to reveal the full extent of the sinister collaboration between the Israeli military in Lebanon and the Phalangist killers in the move to uproot the Palestinian refugee camps. (More information can be found in the very readable The Hundred Years War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017, by Rashid Khalidi.)

Erna Paris had little time for the CCCJ, calling us a “dupe for anti-Israel propaganda,” which was complete nonsense. In reality, the CCCJ favoured a two-state solution but had not taken a position on Zionism. Our intent was to build bridges between the left and the Jewish community.

This was also before a weakened Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in a post-Lebanon war stage negotiated a bad deal with Israel in the 1993 Oslo Accords, which turned the newly established Palestinian Authority into the security subcontractor for the ongoing Israeli military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

To paraphrase a dated romance novel, the left is a many-splintered thing. And so, the desire to stake out a clear position on Israel within the CCCJ led to the unavoidable fracture.

Some members of the organization thought that left-leaning people either did not understand antisemitism or were antisemitic themselves for their opposition to the Jewish state and the right of Israel to exist. (Erna Paris alluded to the latter in her discussion of the far left’s support of the 1975 UN “Zionism is racism” resolution.)

The late York University professor Howard Buchbinder took a different tack within the CCCJ. Originally an American, he had moved to Israel in his youth, served in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), and met his first wife in Israel. Both became thoroughly disillusioned with the direction of the state, and viewed the emphasis on antisemitism on the left as a distraction from the larger issues in the Middle East.

Richard Lee caused a kerfuffle within the CCCJ when he wrote an academic paper comparing the treatment of the Black and brown population in South Africa under apartheid to the system of segregation and discrimination directed against Palestinians in Israel and the occupied territories.

He was hopeful that the latter would not last because of “the deep tradition of humanism and ethics” inside Israel. In contrast, for Lee the South African apartheid system under a fascist regime was a harder nut to crack. It turned out that apartheid would end 12 years later in South Africa, while matters continued to go from bad to worse for the Palestinians.

Meanwhile, Ester Reiter says that today in 2021 she has no difficulty agreeing with the apartheid description applied to Israel, but didn’t feel this way in 1982 when that position was considered extreme within the CCCJ.

Reiter also notes that the CCCJ fumbled the ball by inviting Palestinian scholar Sami Hadawi, the author of Bitter Harvest: A Modern History of Palestine, to address an assembled audience of aging Jewish leftists and Holocaust survivors at the Winchevsky Centre in Toronto. A young woman rose to challenge the reference to “the so-called six million” (the number of Jews murdered in the Holocaust) among the speaker’s writings on the literature table. This set off an uproar that effectively ended the evening.

Richard Lee was not at this dreadful meeting, and says he personally knew a better candidate from the local Palestinian community who would have been less inflammatory and more intelligent for such an event.

Flash forward to 2021 and things look a lot chillier than they did 40 years ago in Israel and elsewhere. White nationalism is on the rise in the U.S., Canada and Europe, and along with this has returned what is referred to as the old antisemitism, with its age-old offensive stereotypes and tropes about Jews.

But this is not the priority for Irwin Colter, a former minister of justice and highly regarded human rights icon who has advised both Nelson Mandela and Soviet dissidents.

Cotler is the Canadian government special envoy on antisemitism, appointed to promote the adoption by governments and institutions of the IHRA definition of antisemitism. It was established to target “the new antisemitism” — primarily criticism of Israel, ranging from benign political commentary to the tougher words used by so-called “anti-Israel” folks, such as settler colonialism, racism, Jewish supremacy and pogroms, to characterize apartheid in Israel and the occupied territories.

Today we also have Independent Jewish Voices Canada (IJV), which has developed a public profile for Palestinian rights. It is hard to compare or contrast it with the CCCJ, since the latter was an organization of its time. One similarity is that IJV has to grapple with and discourage potential activist allies from using political signage and rhetoric containing antisemitic words, says sociologist and active IJV member Sheryl Nestel.

But what about the offensive language directed against Palestinians, as witnessed in Jerusalem with Jewish settlers marching with the slogan “Death to the Arabs”?

Nestel says she has heard of an effort to define anti-Palestinian racism, much as has been done with antisemitism. But she is not sure that is a good idea, while affirming the need to combat such racism. “I think there has to be a recognition or realization of anti-Palestinian racism having a specific form, but I wouldn’t want to codify it,” she adds.

This phenomenon was not discussed in 1982 within the CCCJ. We came together appalled by the events in Lebanon, but quickly became absorbed in the travails of the Canadian Jewish community. I don’t think we discussed the Nakba either.

In writing about the CCCJ, I wanted to demonstrate how the issues of Israel-Palestine have evolved among activists, especially among progressive Jews of my baby-boom generation.

Paul Weinberg is an author, independent journalist, and longtime contributor to rabble. He is also a member of Independent Jewish Voices Canada.

Image courtesy of author