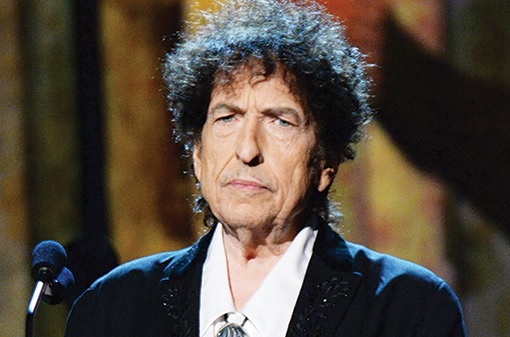

Bob Dylan’s Nobel prize for literature is richly deserved; it was an audacious and inspired choice. Some of his songs are better than others, and you can’t point to any one song and claim greatness for it. But one has to take Dylan’s entire oeuvre as one thing: a cartography of the American mythos. He has extended an enormous reach through space and time.

Some people are already making their displeasure known. They’re whinging that he’s a musician, not a poet. That he might be in contention if there were a Nobel awarded for music. Yet we know that the earliest poetry was sung. Where does the word “lyric” come from, after all? In any case, how do we want our poetry? On a page to be read? Spoken? Sung? That he sang it instead of speaking it strikes me as an unimportant, indeed a trivial, distinction.

There is also the inevitable plagiarism charge. I was unfriended on Facebook by a self-styled Shakespeare scholar for saying this, but Shakespeare himself plagiarized with abandon. All but two of his plays had borrowed plots. Othello and Romeo and Juliet were particularly egregious in this respect. Plutarch was quoted almost word for word in Antony and Cleopatra.

Today’s hypervigilance about plagiarism extends too far. A surveyor of an entire cultural milieu will inevitably find an aesthetic vocabulary that includes some work by others. If it is transformed and re-purposed, I don’t see the problem: as T.S. Eliot put it, “bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.” The Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid plagiarized considerably, but his serial collages had their own life and purpose. And the folk tradition within which Dylan worked always builds upon what has come before, re-using tunes and tropes whose origins, in many cases, are ancient and obscure.

I have not listened to much of Dylan’s later work, although I’m told that Oh Mercy contains some good material. I felt he was effectively plagiarizing himself in those years: that he was derivative of himself. But the first twenty or so albums, taken together, are more than enough to merit the Nobel.

The greatest poets get out of the way. How much about Homer do we learn from reading the Iliad or the Odyssey? What do we know of Shakespeare’s personal predilections? I won’t put Dylan in their company, of course, except to note that all of them soaked up the culture of their time like sponges, and transformed it into something at once new and yet perfectly recognizable. It’s like stumbling down a street that you think you’ve never seen before, and then you stop in front of your house, wondering.

This is why the various voices we hear in Dylan’s work, his thankfully brief Christian period, for example, are but a refraction of the cacophony in which he is immersed. Dylan himself is trying on the guises that surround him. That’s what a skilled observer does: it’s a kind of aesthetic participant-observation.

In Dylan we can see and feel the American time/space landscape, the voices, the sensibility of the time, but we can also perceive the timelessness of myth. “All Along The Watchtower” ends like that: there’s a story about to happen, but it’s a side-issue. The main theme, caught up in a frozen, timeless landscape, is the feeling of suffocation and alienation that the current world evokes. The Western theme, so central to the American narrative, is brilliantly realized in John Wesley Harding and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. The protest work reflects and transforms what was in the air.

Dylan gave the Zeitgeist a voice. Incidentally, some folks didn’t like that voice. That never concerned me: and his phrasing, in any case, was first-rate.

The effect of Dylan’s work was seismic. I couldn’t say the same for Nobel laureate Pearl S. Buck.

The Committee didn’t expand the definition of literature: it returned it to its roots. High time. This modern-day troubadour was not only a (not the) voice of his generation: he has produced a prodigious amount of work that, taken in its entirety, follows Ezra Pound’s dictum: Make it new. And it remains that way.

Kudos.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.