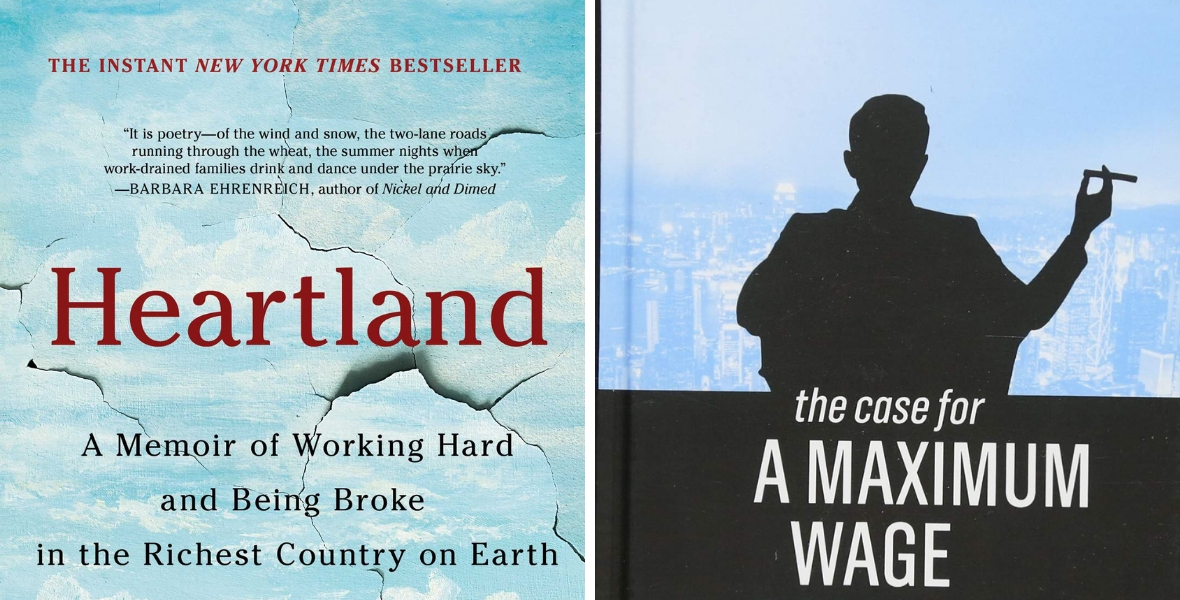

The Case for a Maximum Wage, by Sam Pizzigati (Polity Press, 2018).

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, by Sarah Smarsh (Scribner, 2018).

This past September, the media revealed that online retail billionaire Yusaku Maezawa had ponied up for a ticket to ride a SPACEX rocket around the moon. Although the sticker price is unknown — and really, if you have to ask, etcetera — it’s rumoured Maezawa will pay tens of millions for his trip.

Space tourism with one of many competing egotists — Branson, Bezos or Musk — is only the latest example of conspicuous consumption by the ultrarich, a group that author Sam Pizzigati says we simply can no longer afford.

In his small and cheerful book The Case for a Maximum Wage, Pizzigati explains: “We would prosper, in every sense, without them. Their presence coarsens our culture, erodes our economic future and diminishes our democracy.” And since a great deal of wealth is built on ruinous extractive industries, he concludes, “the wealthy may pose our single biggest obstacle to environmental progress.”

What to do? In a few short chapters, Pizzigati lays out a handful of what he calls “predistributive” measures to reduce corrosive inequality by preventing the concentration of wealth in the first place.

Despite what the book’s title implies, Pizzigati is talking about income, not wages. For a start, he proposes setting a maximum income level, at some multiple of the minimum wage, and taxing personal income above this level at as much as 100%.

Absurd, no? But not unprecedented. The author points out that during World War II, the United States imposed a tax of 94% on income over $200,000. The taxes were quickly reduced once the troops came home and government returned to its peacetime job of representing millionaires.

Pizzigati argues government action should focus on corporations. He calls for sunshine laws to reveal ratios between the highest paid executive and the lowest paid worker. And he proposes governments tie subsidies, tax breaks and contracts to having rational pay ratios.

As he points out, “Tax dollars, Americans have come to believe, should not subsidize enterprises that increase racial or gender inequality … they should also not subsidize enterprises that widen economic inequality.”

Pizzigati reassures readers that the elites — the economists, politicians, political organizations through Europe, the Middle East and the United States — are articulating some of the same solutions. His examples are as diverse as French Presidential candidate Jean Luc Mélenchon, writers in Foreign Policy, and Cairo’s Arab Spring rebels. Administrations as different as the Mondragon commune and the State of Rhode Island have put some of these measures in place.

Some will dismiss all this as naïve. Pizzigati himself acknowledges how fiercely the wealthy have pushed back over the past 50 years against even modest tax increases and social welfare programs. Others will object that these measures prop up capitalism rather than dismantling it. And there is a further issue of how to build broad support for reining in the super-rich since, as PIzzigati points out, most citizens have never met any.

This is certainly the case for the families featured in Heartland, by Sarah Smarsh. Her extended Kansas family of working and rural poor defined wealthy as anyone who could shop every weekend at the Wichita mall.

In her book, subtitled “A memoir of working hard and being broke in the richest country on earth,” Smarsh documents the hard scrabble existence of families in what is casually dismissed in American politics as “fly-over country.”

Heartland is a multigenerational study of the lives and disappointments of America’s underemployed and underpaid, those who labour in the Piggly Wigglys, the KFCs, the small farms and trucking companies, the chicken processing plants.

It’s also, in part, Smarsh’s answer to the questions, “What’s the matter with Kansas?” and “Why does small- town white working class America vote against its own best interests and return Republicans instead of Democrats?”

For Smarsh, part of the answer is the American dream — the belief that if you work hard, you can make good. Failure to prosper results in shame, because in America poverty implies bad choices, laziness, and moral failure, “a failure of the soul.”

Political confusion ensues, as “society’s contempt for the poor becomes the poor person’s contempt for herself. For this reason, in many cases no one loathed the concept of ‘handouts’ more than the people who needed them.”

And thanks to what Smarsh describes as the vitriol of cable TV and conservative talk radio, the Democrats are firmly established in proud rural communities as the party of handouts. Republicans win out as the party of “helping people help themselves.”

For those completely unaware of the lives of the white working class, Heartland is the detailed field guide to Middle America you’ve been looking for. But the lives of Jeannie, Theresa, Chic, Betty, Arnie and many, many others who populate the memoir are presented in excessive, overwhelming detail.

Heartland is also marred by an introduction, conclusion, and periodic asides addressed to a never-conceived daughter — half imaginary friend, and half moral and spiritual compass who was part of the author’s internal life from her childhood until her thirties.

This jarring quirkiness is unfortunate, because Smarsh has a gift for crafting vibrant images and stating overarching truths. For example, on the absence of class awareness, she writes:

That we could live on a patch of Kansas dirt with a tub of Crisco lard and a $1 rebate coupon in an envelope on the kitchen counter and call ourselves middle class was at once a triumph of contentedness and a sad comment on our country’s lack of awareness about its own economic structure. Class didn’t exist … you got what you worked for, we believed.

Now neither Smarsh or any of her small town family would ever meet a towering billionaire like astronaut Maezawa. And even if they did (both Smarsh and Pizzigati agree), most people would be entirely unlikely to connect their misfortunes to the existence of the super rich. But Kansas, and the rest of the “fly-over” world could be a lot better off if, on Maezawa’s return, he was greeted with a hefty tax bill instead of champagne.

Mary Rowles worked in the Canadian labour movement for 33 years. She resides on B.C.’s Saltspring Island and qualifies as one of Alberta premier Rachel Notley’s “unicorn jockeys.”

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!