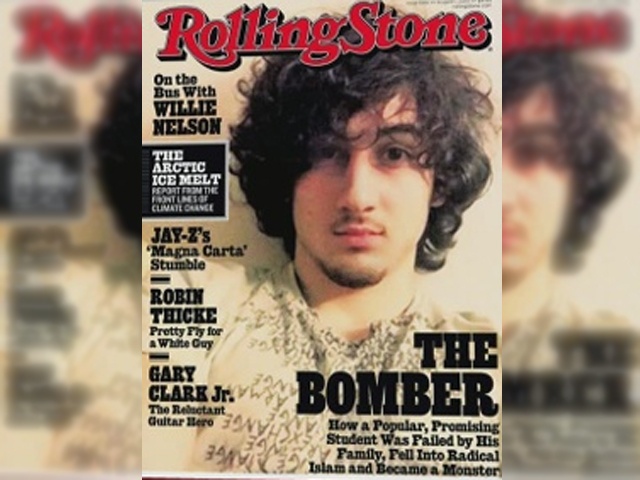

I am probably an exception, but seeing Dzhokhar (Jahar) Tsarnaev on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine does not outrage me. I’m not a regular reader, but the heated debate around the publication of a profile on “The Bomber” caught my interest.

Once I read the feature accompanying the hazy, stylized cover photo — reminiscent of young rock star (eliciting strong reactions) on the brink of stardom — I was convinced it was an important story to tell. This was accompanied by the familiar sinking feeling that I need to retract anything that could be misinterpreted as “terrorist sympathy.”

I am tired of feeling apologetic for wanting broader stories told in the media and for a more empathetic look that subverts our understanding of the “Other.” I do not see any harm done in placing young Jahar on the cover of a major publication. Until now, his motivations have remained largely a mystery, and his actions are surmised to be the outcome of vengeful and maladjusted behaviour. We can’t gain all our insight from a profile, written by Janet Reitman, of the young man involved in a contemptuous infringement on American national security, but we have started asking questions. I applaud Rolling Stone for the move.

At the same time, the speculation can continue. Jahar cannot speak for himself, which allows him to be presented through many different narratives at once. The cover photo gives a glimpse of his coy, boyish naivety. It depicts his White skin, and a sort of teenage aloofness that has reportedly made him the subject of female adoration. Yet, it also asserts his difference — his immigrant roots, his Muslim background, his terrorist affiliations and points to “the monster he would become.” Numerous accounts confirm the Tsarnaev brothers acted of their own will in executing the Boston Marathon bombings, without connections to terrorist organizations. This prompted a strong “unease” within the city at how local this act was, and at just how many Jahars could be bred in Cambridge.

From most angles, Jahar’s could have been the ideal American story, embracing all the glory of opportunity. His coach tells Reitman, “This was the quintessential kid from the war zone, who made total use of everything that we offer so that we could remake his life.” Instead, for the American psyche, he manifested the opposite: a failed experiment of integration. This is easier to digest rather than to reflect on what differentiated Dzhokhar from Jahar — the “Americanized” name he used around his peers.

The article touches on the pain and trauma that an immigrant arriving from a country rife with conflict may feel — the sudden dispossession, and the constant split of two worlds. “There are many things about Jahar that his friends and teachers didn’t know, something not altogether unusual for immigrant children, who can live highly bifurcated lives, toggling back and forth between their ethnic and American selves.” It also mentions, in passing, the pricing out of low-income families in Cambridge. The expensive standard of living tends to be racialized and inevitably contributes to heightened segregation — something experienced by Tsaernaev’s family.

The piece reveals a boy searching for something bigger than himself, frustrated at the opportunities he feels he was denied and desperate for an escape. His family’s income troubles, his parents’ failed marriage, increased class divisions in his hometown and probable unresolved trauma from migrating to America at a young age all contribute to this sense of displacement. By all indicators, his older brother’s embrace of radical Islamic ideology fed — and exploited — Jahar’s “need to belong.”

These are some of the conclusions drawn from months of Reitman’s interviews with Jahar’s peers, teachers, neighbours and classmates. It’s an outsiders perspective, but it’s one of the few that reveals the troubling way in which men like Tsaernaev and his brother engage in terrorist activity, finding an horrific and murderous outlet for their personal feelings of isolation and identity formation.

In Jahar’s case, these feelings seem not to have been externalized — countless interviewees expressed there were simply no “cracks” to show he’d fallen off track. Seemingly, there was nothing explicit to hint at the troubling turn his life would take, nor at the deep void he felt within.

We spend countless TV hours obsessed with portrayals of serial killers, rapists and mass killers and why they do what they do, but when anomalies like Jahar emerge, we’re reluctant to open a conversation. Are we more likely to want to know what motivates those who look more like us, but diverge so inexplicably? Is this why Jahar, who is an immigrant like myself, and his story is of interest to me?

America is uncomfortable questioning its sense of self and its identity. The sentiment goes: those on the outside should make a greater effort to join the ranks. So, the disproportionate responsibility falls on immigrants to quietly sweep away their stresses and not speak about their situation, unless it fits into a certain paradigm of success.

The Rolling Stone piece is in no way a sympathetic account. It simply provides an opening on a story left untold. Rather than reflect on why this is so, the reaction has been that we are glorifying a monster’s tactics and potentially encouraging copycats.

These are familiar, but unfounded, reactions. The magazine generated more publicity than it has in twenty years through this publication. It also showed, in some small way, that “monsters” hiding in our realm might come from a place not too unfamiliar.

Image: www.policymic.com