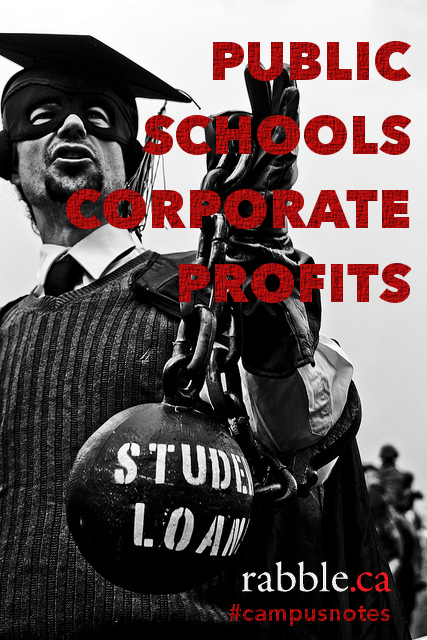

The firing of outspoken University of Saskatchewan Dean Robert Buckingham this May raised questions not only of academic freedom, but of the ongoing transformation of Canadian post-secondary institutions as sites of private profit rather than public education. rabble.ca is proud to launch this special summer series on the corporatization of Canadian universities, by USask Professors Sandy Ervin and Howard Woodhouse. See their previous entries here, here and here.

Universities in the Western world have been important cultural centres since the middle ages. Libraries, rare book collections, archives, art galleries, museums, and art collections are touchstones to the past and the present. Without them, universities today would be impoverished and the process of learning undermined. They are central to the teaching, learning and research which are the distinctive core missions of any university.

As universities are systematically defunded by governments they look for other sources of revenue. Among these are cuts to the funding of libraries as well as their closure. The embargo of books and periodicals in buildings to which there is little or no access is now commonplace. Despite the importance of digital materials, it is difficult to see how scholarship and research could thrive in a university without books. And yet, the former provost of the University of Saskatchewan recently declared without a trace of irony, “Step inside any library where students are gathered, and what they have in front of them are laptop computers, not books.” The fact that an academic vice-president could publicly express such feelings indicates the extent to which the ideas of the corporate media cave pervade the thinking of some senior administrators. (The provost later resigned for having issued a letter of dismissal to Dr. Robert Buckingham, Director of the School of Public Health, and ordering him off campus for having written publicly about the muzzling of deans — see our first article in this series.)

This same disregard for books is mirrored in policies which aim to dispose of cultural artifacts for monetary purposes. For example, senior administrators at the University of Saskatchewan sold 69 pieces of Aboriginal art in an online auction in Calgary in March 2014. Levis Online Auctions placed an estimated price on all the artifacts ranging from $20,570 to $28,084. The total sale price was only $7,176. Careful scrutiny shows that all 69 pieces of art were sold for far less than the lowest estimated price — a bargain basement sale for anyone in the art market.

When asked about the sale at the annual General Academic Assembly in April, then-president Ilene Busch Vishniac denied any knowledge. When prompted by her “trusty assistant” later in the meeting, she declared that the art pieces belonged to a private owner, not the University. This turned out to be false. A month earlier, the owner of Levis Online Auctions had confirmed that “the works came from the University of Saskatchewan.” In May, Busch Vishniac was dismissed for her part in the Buckingham affair.

In a subsequent email, the executive assistant to the president admitted that a private donor had “signed over ownership of the pieces to the University to ‘do with what they will.” In other words, the University did own all 69 artifacts, and the senior administration had decided to sell them off at a fraction of their worth.

An alumna of the University, herself an artist, was shocked by the administration’s “cultural insensitivity and financial ineptitude.” She sent a letter to the editor of the Saskatoon StarPhoenix in May which was never printed. It is worth quoting in part:

“The sale makes a mockery of the University of Saskatchewan’s TransformUS Action Plan, which identifies ‘the creation of a framework for engaging with Aboriginal communities…as foundational to our future success.’ How can Aboriginal peoples put their trust in the University’s engagement plans when it shows so little respect for their cultural artifacts?

“Furthermore, how much faith can the general public have in the capacity of senior administrators to handle and accurately report the millions of dollars of tax payers’ money making up the University budget? When they are so inept as to sell Aboriginal art for a considerable loss, how can their claims of a $44.5 million deficit be trusted?”

Bear in mind that the alleged deficit was the main reason for TransformUS, the plan to restructure the University, close four libraries, “amalgamate” several humanities departments, and “downsize” 160 staff.

In comparison with the suffering involved when people lose their jobs and are marched off campus, the sale of 69 pieces of Aboriginal art might seem insignificant. But the University has a responsibility to act as a repository for artifacts that have been donated, especially Indigenous pieces.

Who made the initial decision to sell the art? The answer lies in the labyrinthine committee structure involving senior administrators. But final approval was in the hands of the Board of Governors (BOG) as the body responsible for fiscal oversight and the administration and management of property, revenues, and finances. As indicated in our third article, the BOG at the University of Saskatchewan overwhelmingly reflects resource, property development, and financial sectors. There are no artists, cultural sector workers or officials from First Nations or multicultural organizations. And the Chancellor, who is First Nations, owns an oil company. This bias in the composition of the BOG may account for the fact that they were only too willing to sell off 69 pieces of Aboriginal art at a loss. The amount of money involved probably seemed trivial to those members of the BOG used to handling millions of dollars, and by using an online auction in Calgary, there was a chance the local Aboriginal community would not find out about the sale.

As chair of the BOG, Susan Milburn was also a member of the powerful Human Resources and Governance and Executive committees. Did she play a part in deciding to sell the Aboriginal art? As a financial adviser, did she and others miscalculate the equilibrium point at which the market would give a fair price? Whatever the answer to these questions, she is stepping down as chair of the BOG, following a protracted dispute over her eligibility to continue in the position. According to a July 19 article in The StarPhoenix, some members of the University believe that Milburn is “a central figure in the deepening controversies plaguing the university, including the decision to hand tenure veto power to the president.”

This decision enacted by the BOG in 2012, which gives presidential veto over any faculty member approved for tenure by established procedures, seems in violation of the University Act.

In order to prevent universities from selling off pieces from their art collections, whether for profit or loss, we suggest the following measures:

- Broaden the membership on BOGs to include artists, cultural workers, and officials from First Nations and multicultural organizations, who understand the non-monetary value of art owned by universities.

- Ensure that Aboriginal art and artifacts are protected from sale as part of the cultural heritage of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit societies.

- Enable public scrutiny and accounting of all private donations — whether artistic or financial — by the entire university community.

- Hold BOGs publicly accountable for all financial decisions.

- Restrict the number of corporate representatives on BOGS to no more than one.

Howard Woodhouse is Professor of Educational Foundations, co-director of the University of Saskatchewan Process Philosophy Research Unit, and author of Selling Out: Academic Freedom and the Corporate Market (McGill-Queen’s University Press 2009); Alexander (“Sandy”) Ervin is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Saskatchewan and a long-time board member of CCPA (Saskatchewan). His most recent book Transformations and Globalization: Theory, Development, and Social Change is in press with Paradigm (2015).