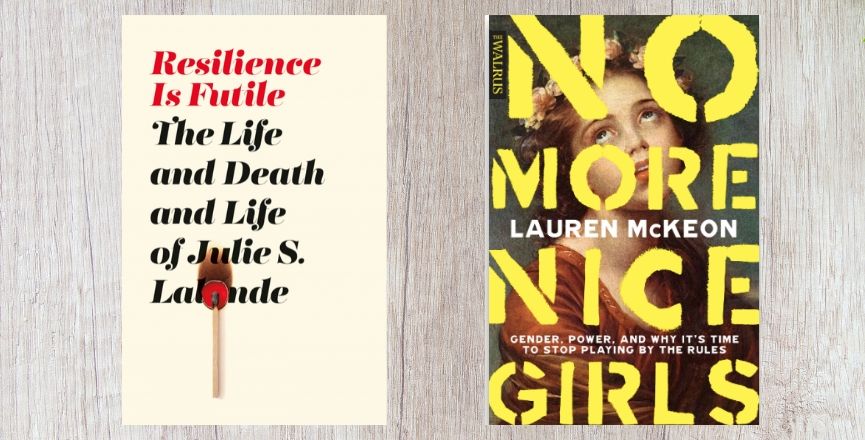

No More Nice Girls: Gender, Power, and Why It’s Time to Stop Playing By the Rules by Lauren McKeon

(House of Anansi + The Walrus Books, 2020, 22.95)

Resilience Is Futile: The Life and Death and Life of Julie S. Lalonde by Julie S. Lalonde

(Between the Lines, 2020, 23.95)

From the time we’re young, the world tells girls not to take up too much space. Be nice, we’re told. Be small. Don’t be too loud. Yet, there’s another message women and girls of recent generations have been fed on repeat: You can be whatever you want to be. But the road to leadership and achievement is one lined by institutional and systemic barriers. According to No More Nice Girls: Gender, Power, and Why It’s Time to Stop Playing By the Rules, a new book by journalist Lauren McKeon, current power structures aren’t built for women to succeed.

“Women and others who’ve been historically excluded from power are more likely to battle gargoyles, to traverse rickety bridges (if there is a bridge at all), to leap over rusty spikes in the road. And god help them if they don’t do it all while smiling,” writes McKeon, the award-winning writer, editor, and author of the previous book F-Bomb: Dispatches from the War on Feminism. Often called “too nice” for leadership herself, McKeon has written a groundbreaking book that asks women to consider “that if all women are set up to fail, it stands to reason that Indigenous women, women of colour, women with disabilities, homeless and precariously housed women, and those who are LGBTQ+ are only set up to fail more and to fall harder.”

In No More Nice Girls, McKeon argues that we’re so often fixated on smashing glass ceilings and replicating men’s visions of success and power that we fail to “examine a deeper, less considered problem: that is, what the ‘view from the top’ looks like for women once they’re there.” She questions how leadership might change if we stopped casting women and other excluded communities in roles traditionally written for affluent white men.

In doing so, she suggests we create a new definition of power and embrace many expressions of leadership, citing examples of survivor-led, community-centred social justice movements and structures that are less hierarchical. “Rather than accepting the solution of a slow, long haul to equality, we can work to divorce agency — and its corresponding qualities of aggression and competitiveness — from our definition of good leadership,” she says.

Through a wealth of examples of women and communities working to topple power structures in a variety of sectors, No More Nice Girls is a thoughtful, bold read that envisions a future in which women create new styles of leadership. It’s one of several recent books that urge readers to challenge standard toxic visions of power.

Another is Resilience Is Futile: The Life and Death and Life of Julie S. Lalonde, a memoir of trauma, strength, and one woman who uses her voice to challenge expectations and to insist on change. Written by survivor, advocate and public educator Julie S. Lalonde, Resilience is Futile is the author’s candid story of experiencing intimate partner violence and stalking by her ex-partner for over 10 years.

Like women we meet in No More Nice Girls, Lalonde herself was conditioned to be a “good girl” — the title of her book’s first chapter. “I was smart and eager and was raised to always be kind,” she writes. “That’s why he noticed me,” she says of Xavier, the abuser who tormented her until his death in 2015. “… he looked at me with the smirk that we teach young women to recognize as flirting; he teases you because he likes you,” Lalonde writes of the way we teach girls to take cruelty from boys as a compliment.

Lalonde, like many women fleeing violence, found herself navigating a misogynistic system, or rather systems, that silence survivors, among them a police force that failed to take her complaints seriously and a justice system that seemingly favours defendants. Eventually, she became an award-winning advocate for women’s rights and a public educator working to end violence against women. In one especially difficult-to-read chapter, Lalonde describes the hostile experience of hosting workshops for cadets focused on reducing sexual assault at the Royal Military College in 2014. Here she was met with cat-calls, other harassment, and eventually complaints by men who attended.

Lalonde’s upsetting anecdote resonates with an observation made by McKeon in No More Nice Girls: that too often it is women who are tasked with rewriting gender roles and dismantling the very power structures that oppress them. “As tempting as it may be to put the responsibility for finding solutions in the hands of women and other equity seeking minorities, I wondered how much faster change would happen if men were included in the process,” McKeon writes. “More than that, I worried that any solutions that excluded them would only further entrench the idea of us-versus-them — a binary division that seemed ultimately unhelpful and also utterly beside the point …What if men also had a stake in reimagining power?”

Both No More Nice Girls and Resilience is Futile are about the often-contradictory expectations placed upon women and how #MeToo and similar movements have “restored power to those who have felt robbed of it.” McKeon argues that “perhaps, this volatile, angry time offers an opportunity, too: a chance to create a new definition of power, and with it, a new vision for equity.” But in order to do so, we can’t expect women to be perfect leaders, perfect victims or perfect humans.

“If the world generally expects women to be perfect, it expects women in leadership to be superhuman,” writes McKeon. Lalonde, for example, was expected to be the perfect victim. “Society warns women about the dangers of domestic violence, but it’s all thinly veiled victim blaming — bad men exist, but only stupid women love them and even dumber women stay,” Lalonde writes.

“To overcome hurdles on our paths to power, we’re told to play within the system, but better, smarter. To use it to our advantage. To get to the top of a company, to win public office, to report our assaults, to put ourselves out there,” writes McKeon. “And if we somehow manage to do all these things, and balance all the impossible, contradictory expectations of the perfect boss/survivor/public figure, and find the semblance of success, then the bullshit will stop, or so the promise goes.”

Yet much of Lalonde’s memoir is example upon example of the bullshit not stopping. Told mostly chronologically, Resilience is Futile recounts the many ways Lalonde adapted to protect herself and those around her. “I wanted so badly to seem brave and unbothered,” she writes. Often feeling like a burden, she shielded her family from the truth about Xavier’s abuse, and writes candidly about how she suffered mentally and physically.

When Lalonde felt abandoned by the legal system, she swore off it completely. One might argue women in leadership suffer a similar fate in hyper-masculine spaces not designed for them to thrive. “Throughout much of the modern feminist movement, women have spent substantial time, resources, and energy putting everything we have into replicating men’s visions of success and power, only to discover that things look more unequal than ever once we do,” writes McKeon.

Both books will make readers uncomfortable — and really, they should. Yet despite their fierce takedowns of gender inequalities, both offer optimism and concrete examples of how speaking one’s truth can itself be a form of power. When reading Resilience is Futile, you can’t help but be motivated by Lalonde’s ability to regain control of her own life while improving the lives of countless other women, and No More Nice Girls is groundbreaking in its ability to encourage all women to rethink, reclaim, and overturn power whether they uphold a leadership position or not.

McKeon summarizes the book best in the following line: “The is not about demanding a seat at the table at all. It’s about building our own fucking table, and making it look completely different,” she writes.

Let’s build that fucking table.

Jessica Rose is a writer, editor, and reviewer who has written for publications across Canada. Her book reviews have appeared in magazines including Quill and Quire, Room, Ricepaper, This, and the Humber Literary Review. She also covers Hamilton’s literary scene in Hamilton Magazine. Jessica is a senior editor at the Hamilton Review of Books and a founding editor of The Inlet. She recently took over the role of books editor at This magazine. When she’s not writing, she is the social media coordinator at YWCA Hamilton.

Background image: Lukas Blazek/Unsplash