Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporter of rabble.ca.

Two weeks ago, Stephen Harper announced he would be “giving a boost to some families trying to save money for post-secondary education” by doubling the Additional Canada Education Savings Grants (A-CESG). The A-CESG is one of three grants available through a Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP).

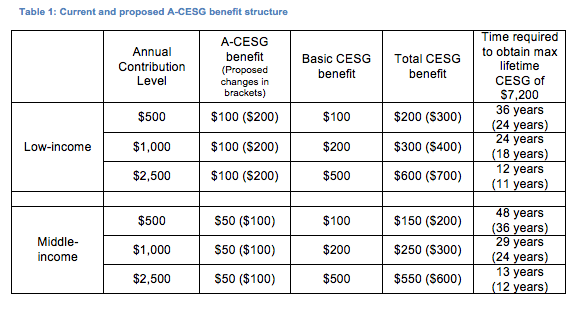

Under this promise a low-income family would receive an A-CESG of up to $200 for the first $500 they contributed to their RESP each year and a middle-income family would receive $100. This would be an increase of $100 and $50 respectively to the existing A-CESG. When you combine this new money with the basic CESG (a top-up grant of 20 per cent to a maximum of $500 annually) a qualifying low-income family could receive up to $700 in total CESG funds compared to the current $600, and a middle-income family could receive up to $600 compared to the current $550.

RESP background: how they’re structured, what’s changed

Though the A-CESG is separate from the basic CESG, it still counts towards the lifetime maximum CESG available to an RESP holder ($7,200), which is now $600 less than one year of average tuition in Ontario. Harper’s proposed “expansion” can only increase the rate at which an RESP holder reaches this maximum. Also, unlike the contribution-based top-up of the basic CESG the A-CESG must be applied for.

Do RESPs work? For whom?

C.D Howe Institute economist Kevin Milligan has found that wealthy households are three-and-a-half times more likely to have an RESP than low-income households. He had this to say about the education investment tool:

- “The RESP bill is bad tax policy and even worse education policy.”

- “It [RESP] adds needless complexity to Canada’s income tax system.”

- “CESG payments end up disproportionately in high-income households.”

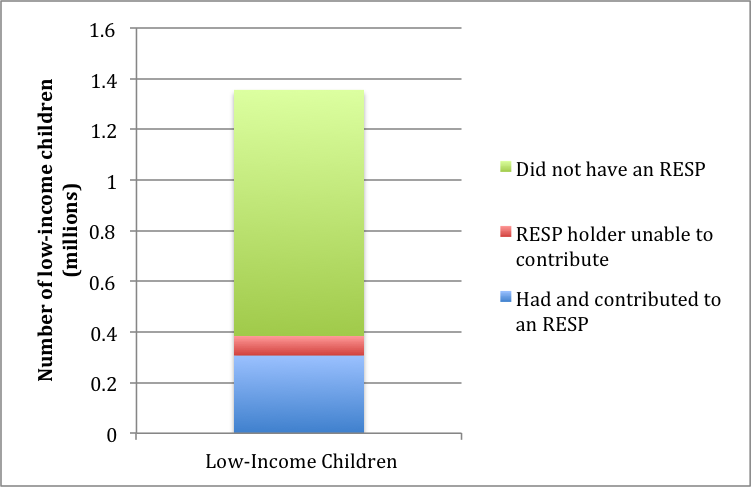

The government’s own reports on the RESP highlight just how ineffective this program is at making post-secondary education more affordable for those in need. Only 28 per cent of children identified as being from low-income households were beneficiaries of an RESP in 2013.

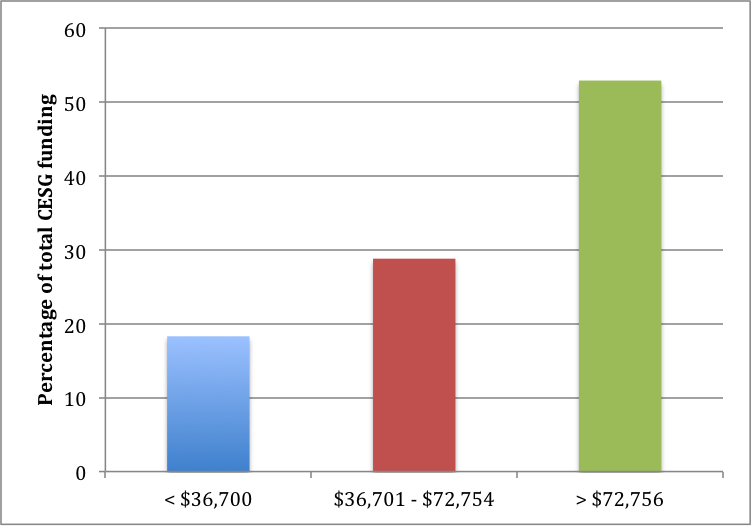

The disproportionate participation rates among higher-income families means that the majority of total funding through the CESG ends up going to wealthier families.

The main driver of the disproportionate CESG spending is that the more one can afford to save, the greater the benefit. This inherently favours wealthier households with greater discretionary income.

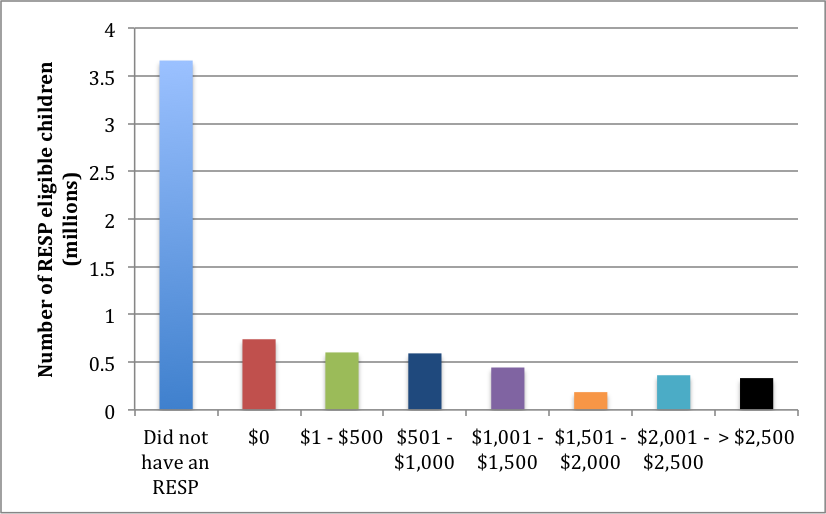

Putting aside the sums of money required to obtain maximum CESG benefits is impossible for many Canadians. Examining average annual RESP contributions showcases this.

Over half (59 per cent) of RESPs received contributions of $1,000 or less in 2013; 41 per cent received $500 or less. Only 10 per cent of RESPs had the contributions required ($2,500 or more) to receive the full CESG benefit of $500.

As Table 1 shows, under the proposed changes to the A-CESG, it would take a qualifying low-income family contributing $1,000 annually 18 years to receive the maximum lifetime CESG benefit, and 24 years for a middle-income family. However, the average age of a child when an RESP is first opened is over three years old. This fact alone makes it very unlikely that low- or middle-income families will be able to save enough to receive the maximum benefit under either the current, or the proposed benefit levels by the time a child is ready to attend university or college.

How much does the program cost, and how could that money be better spent?

At an estimated $1.05 billion in 2014, the RESP as it is currently structured is one of the federal government’s largest expenditures on student financial aid. Despite this significant expenditure, as of 2013 only 47 per cent of all children eligible for CESG had received any money. The proposed changes to the A-CESG are estimated to cost the government an additional $45 million.

The RESP is an expensive program that delivers the largest benefits to those who need the least help. When combined with the ineffective back-end education tax credits, RESPs cost taxpayers an estimated $2.97 billion in 2014.

If this funding was redirected to the Canada Student Grants Program (CSGP), all federal student loans could be replaced with up-front need-based grants within 15 years – without spending an additional penny of federal money. This approach would provide students with immediate and significant debt relief, making post-secondary education far more affordable. It only requires the political will to make this happen.

Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporter of rabble.ca.