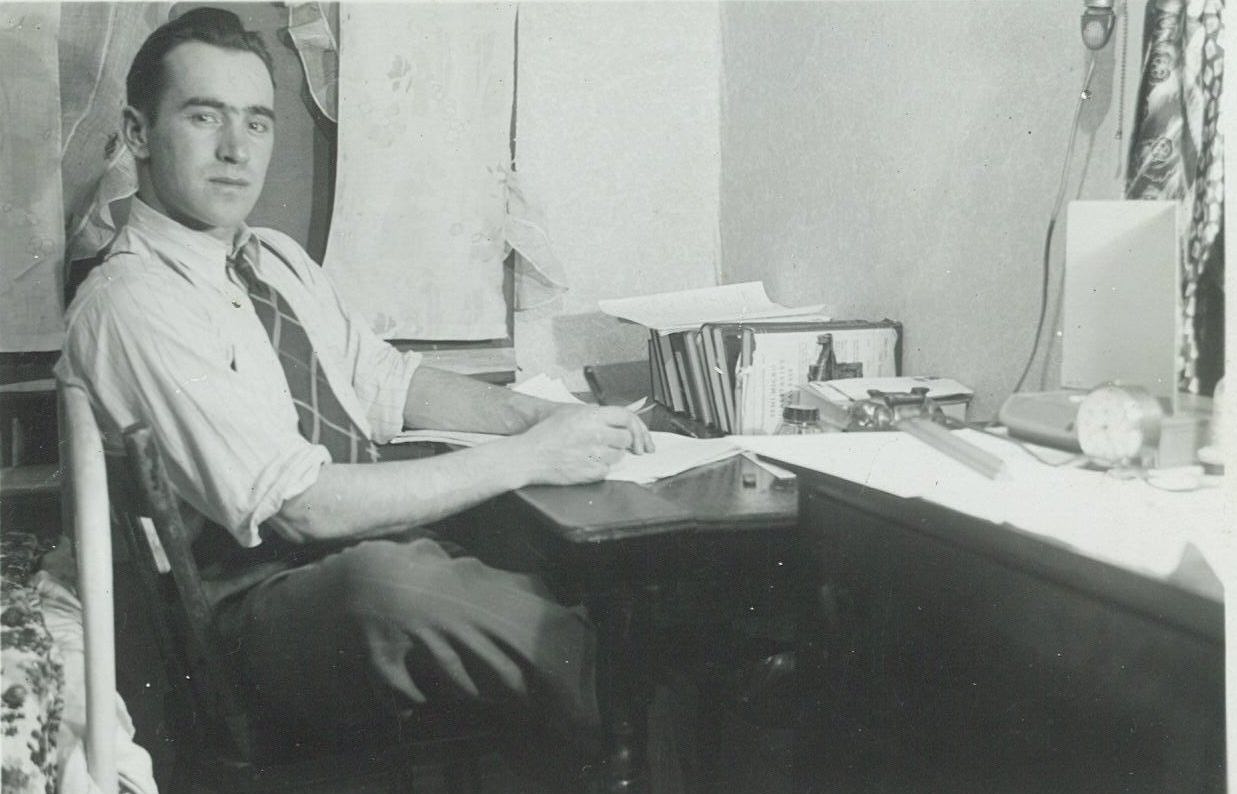

Today is the 100th anniversary of the birth of my father, Dr. John LeRoy Climenhaga.

Dad, who died in 2008, is best known as an astrophysicist, and his name is most often used nowadays in connection with the respected astronomy program at the University of Victoria, and in particular with UVic’s Climenhaga Observatory.

But my Dad’s strong belief in and support for the value of public education — and that included public post-secondary education in all fields, including the arts and pure sciences like his area of studies for which there was no obvious commercial application — is my topic for today.

We live in an era when too many people disparage university programs that do not have an immediate commercial application. My father’s research specialty within his academic field was pretty esoteric — studying through optical observation the amounts of Carbon 12 and Carbon 13 on cool carbon stars. This, as he told me frequently, was unlikely ever to make anyone wealthy, least of all us.

However, he said, it was worth the effort because it offered humanity insights into the origins of the universe and, to my dad’s way of thinking, this was a social good in itself. He was, by the way, a deeply religious person, and his studies had the effect of reinforcing his faith, rather than breaking it down.

He certainly disapproved of the trend among governments and their ideological supporters in his lifetime to disparage and mock academic fields that didn’t offer immediate moneymaking potential for a small group of businesses already established in their industries — often thanks to the help of previous generations of researchers.

Although I don’t recall him feeling the need to make this argument, inevitably when research is done into esoteric scientific fields, and critical work carried out in the arts and philosophy as well, new ideas and approaches emerge, often with revolutionary potential for the improvement of society.

My dad joined the tiny faculty of Victoria College in 1949 as a physics teacher educated at the University of Saskatchewan. He started working on his PhD from the University of Michigan in 1954 and received the degree in 1960.

Dad became the first head of the Physics Department at the new University of Victoria in 1963, the year the university was founded. As his title suggests, it was an unpretentious age compared to the present. He would serve as department head till 1969, when he became UVic’s dean of arts and sciences.

Throughout his teaching career — which continued as Professor Emeritus for a dozen years after his formal retirement — he advocated strongly for the value of publicly supported post-secondary education and the creation of opportunities for students from all backgrounds to pursue high-level academic studies.

This was the reason for his determined support for the creation of a university in Victoria — which, as strange as this might sound to some of us now, was controversial at that time, with a group of academics and administrators at the University of British Columbia certain that establishing new universities in the province could not be a good thing.

As head of physics, he was a major contributor to the creation of what is today one of the finest physics research programs in Canada. He also advocated forcefully for the creation of the university’s astronomy program, which became a reality in 1965. That program too had its opponents, something to keep in mind when we hear the accolades nowadays about the quality of astronomy studies at UVic.

In the 1970s, dad championed UVic’s participation in TRIUMF, the Tri-University Meson Facility located at UBC — another example of esoteric pure research that nevertheless yields commercial value and helps solve human problems.

But it is also worth mentioning one of the great professional disappointments in his life, the failure of the Government of Canada to complete the Queen Elizabeth II Observatory on Mount Kobau near Osoyoos in British Columbia’s Okanagan region. Penny pinching and a mindset of austerity in Ottawa and at some universities led the federal government in 1968 to abandon this project, which would have made Canada the site of the second-largest optical telescope on the planet and a powerhouse in the field.

Having grown up on a farm in Saskatchewan during the Great Depression, dad understood that for many Canadians like him the opportunities of post-secondary study would simply not be available to students from modest backgrounds without a strong public commitment to education. He also understood the huge benefits to all Canadians from public post-secondary education that provides any student with the talent and the drive to have the opportunity to complete post-graduate degrees. This, of course, improved the lives of the student beneficiaries — but it also improved the lives of all Canadians and, indeed, all citizens of the world.

Canada’s strong commitment to public post-secondary education in the postwar period certainly helped make possible my dad’s contributions, from which many Canadians have benefited. Canada would be a better place today, it is said here, if we re-adopted the attitudes held even by conservative governments in the 1960s about the obvious value of public, post-secondary education, and the essential role of governments in that great enterprise!

On dad’s retirement in 1982, the observatory on the roof of the Elliott Building at UVic was named the Climenhaga Observatory in gratitude for his work. On his 70th birthday, he was honoured by the International Astrophysical Union when it assigned the name Climenhaga to an eight-kilometre-long asteroid that orbits the sun between Mars and Jupiter.

Dad was only the second Canadian to be so honoured by the IAU. It is interesting to note that the asteroid now known as Climenhaga — which was discovered in 1917, the year after dad’s birth — was discovered in 2009 to have its own moon!

Dad’s work lives on in the form of a scholarship established in his name in 1984 to assist a senior UVic student in physics or astronomy.

Since my dad’s death, it has our hope in his family that funding for the John L. Climenhaga Scholarship can be made fully sustainable and that scholarships can be granted to additional deserving UVic students in physics and astronomy each year.

Friends, colleagues and family members — or, indeed, anyone so moved — are encouraged to contribute to the John L. Climenhaga Scholarship specifically, or to support of the University of Victoria’s scholarship programs generally.

A donation page devoted to the John L. Climenhaga Scholarship can be found on UVic’s website.

Readers interested in supporting scholarship programs at UVic can also contact the university’s Development Office at 250-721-7624 or 1-877-721-7624, or by postal mail at PO Box 3060, Victoria, B.C., V8W 3R4.

This post also appears on David Climenhaga’s blog, AlbertaPolitics.ca.

Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

![]()