On September 18, after a week of choking on smoke from U.S. climate fires, Vancouver recorded the worst air quality of any major city in the world.

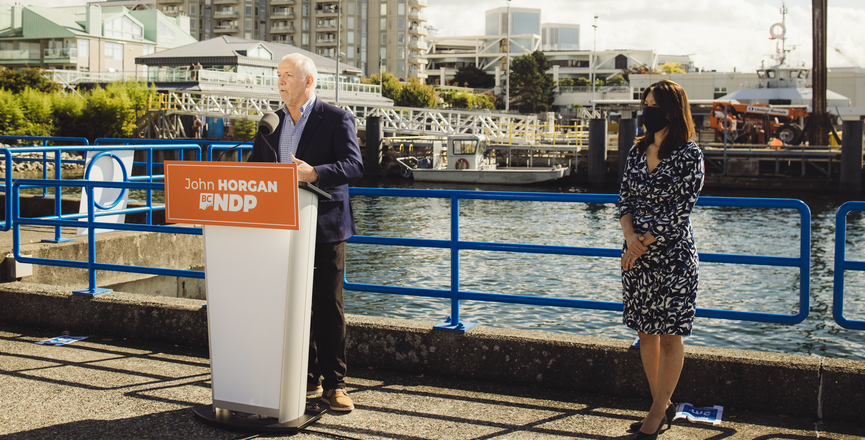

Three days later, B.C. Premier John Horgan, riding high in the polls from his NDP government’s adroit handling of the COVID-19 crisis, announced an early election, mentioning “climate” just once, briefly.

In 2019, the Globe and Mail opined that the NDP had done little to alter the previous Liberal government’s environmental path. That may overstate the case. A Liberal victory would be the worst outcome for a future that is both socially just and environmentally sustainable. Yes, the Liberals introduced North America’s first carbon tax in 2008, the product of then-premier Gordon Campbell’s ever-shifting enthusiasms, but it was modest in scale and not a springboard for further climate action.

More typically, Liberal policy cut back environmental protections and promoted export-oriented, carbon-heavy industrial mega-projects like the Site C dam and fracking-based LNG. As for social justice, as former Liberal cabinet minister George Abbott has just revealed, Campbell’s ideologically driven tax cuts right after the 2001 election decimated social services for the most vulnerable and helped kindle the current opioid crisis.

In opposition, the NDP criticized tax breaks for LNG and then promised to use “every tool in the toolbox” to stop the Trans Mountain pipeline from the Albertan bitumen sands. In 2017, the NDP formed a working alliance with the B.C. Greens and released the CleanBC strategy, with the most ambitious climate action plan of any Canadian province (admittedly an easy bar to jump).

So you’d think that for voters who want no return to the B.C. Liberals’ corporate-oriented politics, voting NDP would be a no-brainer, especially since B.C. Green votes don’t translate into many seats in our antiquated first-past-the-post electoral system.

But it’s not so simple. Many previous pro-environment NDP voters are thinking twice, and it’s not just young people or those working at NGOs.

The Narwhal’s comparison of the NDP’s 2017 campaign promises with its performance in office helps explain why.

It’s, at best, a mixed record.

There has been modest progress on banning fish farms from wild salmon migration routes and updating environmental assessment legislation. Grizzly bear trophy hunting has been banned, and big corporate and union donations removed from politics.

But the government has not yet passed promised legislation to protect endangered species. Environmentalists feel betrayed by the weak followup to the 2014 Mount Polley copper mine disaster and the mostly business-as-usual management of old-growth forests (chop, chop, export). The latest news? Approval for turning parts of an old-growth forest near Prince George into wood pellets for overseas biofuel markets — nobody’s idea of renewable energy!

Incorporating the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into B.C. legislation was courageous, although B.C. government collusion in the militarized RCMP invasion to ram a pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territories shows that colonialism is far from dead.

It’s the interlinked energy and climate files where public policy has the greatest impact on how B.C. deals with the unfolding climate catastrophe, one that will make COVID-19 look like a summer cold.

The anti-pipeline “toolbox” came down to a single long-shot reference case on jurisdiction over bitumen transport, one that the premier seemed anxious to get off his desk. The government opted not to subject Trans Mountain to a “made in B.C.” environmental assessment, even though a Supreme Court decision authorized it to do so in 2016.

However reluctantly, Horgan green-lighted the Site C dam, an expensive legacy from the previous Liberal government.

Site C’s core purpose, argues policy analyst Ben Parfitt, is to provide electricity for the LNG industry, the pipe dream of former Liberal premier Christy Clark. But the Horgan government has offered even bigger tax breaks than Clark did — never mind the environmental impacts of fracking and the dubious long-term benefits to B.C.’s economy.

The government-appointed scientific review panel indicated a “profound absence of knowledge” about relevant impacts, but the NDP leadership accepted the Liberals’ branding of LNG as a “bridge fuel” to a lower emissions future — a notion that recent scientific evidence on methane emissions from fracking has further undermined. And the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers quietly helped ensure that public health impacts were beyond the panel’s mandate.

Overall, according to a Stand.earth report, Horgan has increased subsidies to fossil fuel industries by 79 per cent over the B.C. Liberal government’s level, the province’s $1 billion being second only to Alberta in generosity extended to corporate polluters.

The current NDP program makes no mention of fossil fuel subsidies — promising only to review oil and natural gas royalty credits.

What about investment in renewable energy? According to The Narwhal‘s overview, faced with a glut of energy in B.C., the government has “shut the door” on most new wind and solar projects and has not renewed contracts with independent, small-scale green and clean power projects.

So, the CleanBC climate action plan has praiseworthy goals, including reducing B.C.’s greenhouse gas emissions by 40 per cent by 2030 (from 2007 levels) and 80 per cent by 2050. But as Seth Klein points out in A Good War, those targets are not backed by budgetary allocations, are not actually being met and, unfortunately, are inadequate in light of the latest science. Above all, the LNG project alone will make the targets impossible to meet without devastating the rest of the economy.

Overall, this pattern is what Klein calls the “new climate denialism” — verbally accepting climate scientists’ warnings while avoiding the public policy implications. There are some creditable initiatives, but they amount to using buckets to douse a forest fire. Where is the COVID-level sense of urgency? The apparent strategy: Pick low-hanging fruit to dangle before soft green voters, but don’t tread on the toes of corporate carbon capital. Even if that precludes developing a just and sustainable economy.

What accounts for this pattern?

Climate action is difficult for any government because of the long time range, disruptive changes and indirect benefits.

But B.C. governments face the additional challenge of the disproportionate power of the petrobloc — major fossil fuel corporations and their allies in finance, the media, the government bureaucracy and elsewhere. They can withhold investment, hold hostage whole communities currently dependent on resource extraction jobs (no matter how temporary and unequally distributed) and constantly lobby B.C. public office holders (an average of 14 contacts per workday, according to a Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives study).

Policy elites’ acceptance of neo-liberalism, the ideology of free-market fundamentalism, since the 1980s is another factor. In Canada, neo-liberalism comes marinated in oil and a wilful blindness to the dependence of fossil fuel industries on massive public subsidies. Except for the much-slandered Jeremy Corbyn, former leader of Britain’s Labour party, social democratic parties like the NDP have generally offered little robust resistance or few systemic alternatives to rapacious global capitalism. Many social democrats have internalized the inaccurate neo-liberal dogma that only the private sector can lead growth and create real jobs.

For its part, the civil society environmental movement has attracted thousands of young people, but it has not yet built a broad coalition, which must include a swath of working people and their unions needed to offset the petrobloc’s power.

The B.C. NDP itself has both “green” and “brown” (resource extractivist) wings. Today, the “browns” are in charge, led by Horgan, key senior cabinet ministers and party insiders who are bullish on extractivist overdevelopment.

Yet for all that, the NDP is a big tent that brings together diverse progressive British Columbians, including labour, ecological and Indigenous activists. It has been more willing than other parties to use public policy to offset market failures — and climate change is the biggest ever. (Disclosure: I have been a member for much of the past 49 years.)

What is to be done?

Given the will, how could the B.C. NDP leadership restore its environmental credentials? It could suspend Site C, given massive cost overruns and recently discovered geological hazards.

Similarly, it could suspend support for LNG fracking pending a public health review, proper answers to the questions raised by the earlier scientific review and a reconsideration of its economic prospects.

It could give substance to CleanBC by translating its greenhouse gas reduction goals into budgetary allocations and legally binding benchmarks along the way. As part of a post-COVID recovery, the government could expand investment in green jobs that use the skills of construction and trades workers, and ensure that resource communities are involved in planning for the transition to a sustainable economy.

Part of the reason for the snap election might be the “brown” New Democrats’ wish to govern without the B.C. Greens constraining their extractivist ambitions. Former critics of extractivism too often change their tune or fall silent once they become candidates or MLAs.

An emerging generation of leaders who really get the climate emergency could help change that, backed by a grassroots membership demanding a greater say in making policy. Amongst members who don’t want to be reduced to campaign fodder, and even amongst the heavily whipped caucus, there may be a critical mass of discontent with the party’s “command and control” governance — including bureaucratic obstacles to horizontal communication between riding associations, and to members in some ridings who were blocked from challenging “establishment” favourites for nominations.

Finally, what are the options for the 30 per cent of B.C. voters who see climate change and environment as one of their top three issues but who don’t want a return to regressive Liberal policies? The polls indicate an NDP landslide, so they may feel freer than in previous elections to vote for a candidate they like, rather than against a party they fear.

Progressive advocacy group Dogwood BC is encouraging voters to press candidates for a public commitment to end fossil fuel subsidies, even if it means standing against their own party. Out of that process may come a greener, younger, more climate-savvy legislative body. It’s a long shot, but better than none at all. And it’s no substitute for continuing to build progressive social movements in civil society.

Robert Hackett is a professor emeritus at Simon Fraser University, and co-author of Journalism and Climate Crisis: Public Engagement, Media Alternatives. He is also a member of the NDP and of the non-partisan Burnaby Residents Opposing Kinder Morgan Expansion (BROKE). This article originally appeared in the National Observer.

Image: John Horgan/Twitter