Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

I can remember back clearly to an Indigenous Day rally in the early 2000s — that would be June 21 on the calendar every year, even though it was not celebrated publicly every year.

This was a long time ago from the festivus we have now at Dundas Square, where there is good entertainment and enthusiasm and poor vendors — for the most part the dream-catchers are made in China.

My point here is that National Indigenous Day used to be powerful, political and meaningful; the way Pride used to be political and is now more like picking up the annual T-shirt to prove you were there.

Now the ritual as protest — and the brave coming out together as a group for the ritual — is lost in the numbing commercialism that makes everything shine like it could be gold, but without the necessary alchemy to make it so.

Back in early 2000s, a crowd of thousands gathered in front of Hart House at the University of Toronto on June 21.

I was with my friends when a familiar scent filled the air, the sharp smell of Breakbone Sage (male sage).

We pretty much just followed our noses to the source.

First, there was one woman handing out headband/bandanas to wear, screenprinted with a fist superimposed over a medicine wheel.

Then there was the police who were standing beside her in not quite a line but more like an audience formation and they were just staring. No talking, maybe a quick crackle of their radios but not talking, shouting, swearing… or harassing, beating and arresting.

At first I thought they were glaring at the bandana vendor but there still was the smell of sage.

And following the eyes of the police down I could see what they were all staring at.

A rather large group of demonstrators were gathered around a smudge bowl, patiently waiting their turn to smudge.

What sit-ins and occupations couldn’t do — bring the police to a complete standstill — ceremony could.

If you are curious as to greater detail of what “smudging” is, I can quickly note that it is form of prayer and purification with sacred medicines with are herbs like sage. For a deeper teaching, I suggest contacting your local native friendship centre or health centre if you’re near a reservation.

There was such power in that action, that ceremony, that the moment literally became timeless.

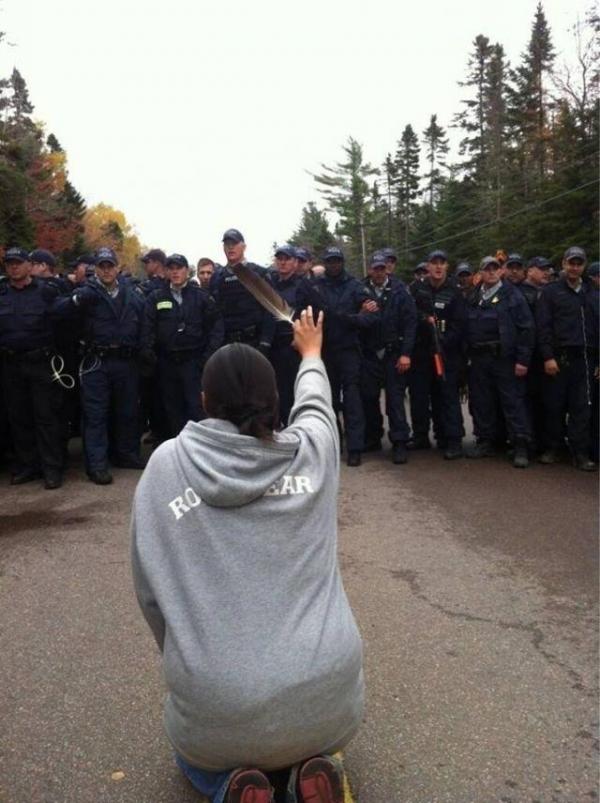

For newer activists, you can feel the same phenomenal power emanating off the infamous photo of a woman holding an Eagle Feather, taken at the Elsipogtog resistance camp in New Brunswick by Ossie Michelin for the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. (I want to give credit where credit is due since the image has now gone viral and has been manipulated. You can read the story about the photo here).

Of the Mi’kmaq and Elsipogtog Nations blockade at the time, I wrote:

“In the photo, she is kneeling in front of a line of armed Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers, holding an eagle feather.

Eagles are one of the most — if not the most — important bird for Indigenous people. It can fly the highest so it is closest to Creator. That is where the eagle and its feathers get their reverence.

So no, she didn’t have a gun or a sword.

Perhaps arming yourself with a feather in the face of extreme police repression — the RCMP had an attachment of snipers in camouflage when they raided the blockade Thursday morning — seems useless.

But with that Eagle Feather, she was protecting her people.”

I revisit my words today because this is the section of the Medicine Wheel that remains the most unbalanced when it comes to activism.

Activists — mostly white men — still lead the movement with their jaw. The involvement in physical, the anger is emotional, the discourse is intellectual… but as for the spiritual…

Sometimes I think it’s because most people are devoid of a spiritual life in their everyday lives, so of course it’s missing in our resistance.

I also think there is trepidation to speak about spirituality since it reflects so much of a person’s inner self and their vulnerable heart which cannot always be safely worn on their sleeve.

Idle No More has helped and is continuing to help open people up to considering songs as resistance, Sacred Fires, Bundles, Drums and teachings from elders.

There is an awesome power in a round dance.

The easy part of the round dance is listening to the drummers and singers. Hearing the voices of the singers — even if in an Indigenous language you don’t understand — rise and dive like Kingfishers and move between the realms of earth and sky is beautiful.

The slightly difficult part is building trust between individuals who are just standing around listening to the drum, and convincing them to reach out and take each other’s hand and start round-dancing.

That’s when the magic happens, when two strangers reach out their hands and connect to form a giant circle which spins around, made up of hundreds of new relationships of trust — and then suddenly the group of dancers are now all connected to one another. And I hope that it is this connection between Indigenous Canadians and mainstream Canadians that lasts well beyond this day of action. No justice. No peace.

The language of human touch carries with it many lessons and instantly breaks down any social-political barriers between the Canadian nation and First Nations across Canada. Aided through the communication of the drum — the thundering power of the human heart — one hand grabs another and a new understanding is built. New alliances. New allies.

This said, tomorrow there is an opportunity to explore how ritual and ceremony provide the space-aside — sacred literally means to be placed aside in an act of reverence — to discuss such topics and I look forward to receiving even more blessing in my life.

There already seems an unspoken protocol that allows First Nation drummers, singers and standard-barrers walk at the front of the march to show respect for the original people and the calling out in recognition of the nations that dwelt on this territory.

I know these are baby steps — and small moments compared to 1999 when First Nations demonstrations occupied Toronto’s Gardiner Expressway or the reaction to the death of Dudley George — but hopefully our hearts can open little by little — to show that we are not ashamed that we actually have a heart.

*Original photo by Ossie Michelin.

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.