rabble is expanding our Parliamentary Bureau and we need your help! Support us on Patreon today!

For the better part of the summer, Beirut has been consumed by a garbage crisis. Trash and household waste have been piling up unfettered in city streets. Despite massive protests, the sectarian government has been intransigent in the face of a swelling health and environmental catastrophe.

Meanwhile, in Paris, governments and corporations have been preparing for the COP 21 UN climate summit. Each of its 20 previous iterations has not failed to deliver dismay and heartbreak to scientists and climate activists. With the symbolic one percent global warming threshold passed this year, it’s no exaggeration to call the Paris talks the most important climate summit in history. And yet, we should expect nothing more than weak targets, equivocation and inaction interspersed with gladhanding and photo ops.

On November 12, 43 civilians were murdered and hundreds more injured by two suicide bombers on motorcycles in southern Beirut, the worst attack since the end of Lebanon’s civil war in 1990. The next day, 139 people were murdered by coordinated gun and grenade attacks in downtown Paris, the worst attack on French soil since the end of the Second World War. ISIL has claimed responsibility for both attacks.

One attack barely registered on the pages of the mainstream western press. The other inspired an unprecedented outpouring of compassion and prayers, alongside the kind of thing that passes as solidarity nowadays: sharing paintings of Eiffel Towers reimagined as peace signs and replacing our social media profile pictures with images of the rouge, blanc et bleu.

It’s hard not to see an allegory in Beirut’s spurned dead and rising tide of waste while the tragedy of Paris is comforted by global sentiment and political spectacle. But more to the point, we can see the ways in which Lebanon’s interminable human tragedy is converted into so much rubbish through the decisions made in the conference rooms of the Beirut of the North.

The histories of Beirut and Paris have been intertwined for almost two centuries. On October 6, 1918, as the victors of the First World War scrambled for control of the widening horizons of the new, Salim Ali Salam convinced the Ottoman governor to leave Beirut and declared it the capital of a new independent Arab state.

The next day, the French navy seized control of the harbour and the following morning a British contingent entered the city. Three days later, the British transferred control of the city to the French who immediately ordered the Arab flag replaced with the tricolor. Not even a week old, and Beirut’s reign as the capital of an independent Arab state was quashed.

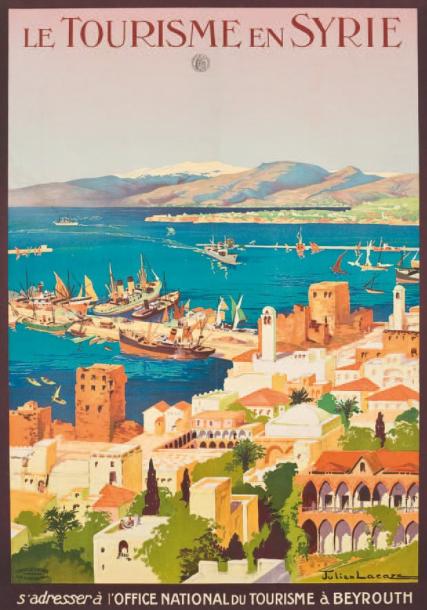

Instead, Beirut became ruling seat of the French Mandate. Its stunning cosmopolitan architecture and world-class cuisine earned it the title “Paris of the Middle East” — an honorific heavy with far more bitterness over what might have been than with the admiration it was meant to denote.

No one calls Beirut the Paris of the Orient anymore. Decades of civil war and political strife have hollowed out the Lebanese capital while Paris continues to hold the western world’s imagination as the city of light, romance and fashion.

Much ink — but much more blood — has been spilled over the question of which lives count and which don’t; which corpses are mournable and which aren’t; which bodies are welcomed into the commonwealth of humanity and which are shunned, cast out, pulverized and ignored. This distinction is not accidental: it is a direct consequence of that morning in 1918 — and the colonial powers of the west continue to protect and cultivate it.

Within a few hours of the attacks, French president François Hollande declared that France would be “relentless” and engage in “pitiless war” against terrorism. Few details are available as to what, precisely, Hollande means — but we can guess. And we can safely predict that none of it will make the former seat of French colonial power in the Middle East any safer.

The attacks will serve to justify an increased security crackdown on the incoming climate activists and advocates, quieting the urgency of the best chance we have at halting the imminent two-degree warming of global atmospheric temperatures. Beirut, a coastal city with few fresh water reserves, will look upon its trash-strewn streets as a minor inconvenience in comparison.

The anti-immigrant right is already marshalling its forces to cast blame for the attacks on refugees, who will now find even more closed doors, more police harassment, more racism and more misery. France will provide cover for this racism by turning its surveillance and security apparatus against the unmournable bodies already inside its periphery: immigrants, French citizens of colour and any other bodies whose sheer existence stand as a rebuke to the national myth of liberty, fraternity and solidarity.

There are almost 315,000 registered Syrian refugees in Beirut and 1.1 million in Lebanon — 25 per cent of its total population. As of September, there were 6,700 in all of France.

And, of course, the reactionary battle cry will increase pressure for all western governments to bring their war machines to bear upon a region that has seen far more than its share over the past two centuries. “Vos guerres, nos morts” was one slogan circulating after the Paris attacks. Yesterday, Ottawa Citizen columnist Terry Glavin literally called for “ceaseless war” in response to the attacks.

Beirut’s garbage crisis, its political paralysis, its influx of refugees and its unmournable bodies are all corollaries of that morning in 1918 when Arab voices in Beirut and across the Levant were ignored in favour of western imperial interests. The west will continue to laud the cosmopolitanism of Paris without asking if its worldliness is the consequence of a drawing-in or a forcing-out.

To one city: wealth, esteem, power and romance; to the other: war, strife, corruption and resilience.

Yes, it would be nice if, for a start, we would mourn Beirut bodies as we do Parisian ones. But far more urgent is a real reckoning of why this distinction was made in the first place — and why we allow it to endure.

rabble is expanding our Parliamentary Bureau and we need your help! Support us on Patreon today!