A colleague of mine pointed out a relatively new paper about the distributional impacts of B.C.’s carbon tax. In my work, we look at actual energy expenditures by different household groups, and because lower-income groups spend a greater share of their income on (carbon-intensive) energy, any carbon tax is regressive. But that regressivity ultimately depends on what you do with the revenues, and can be compensated with a credit. In B.C.’s case, when the carbon tax was instituted, there was a decent low-income credit that made the overall regime progressive, but as the tax increased from $10 to $30 per tonne, the credit did not keep up, and the current regime is regressive. Not massively so, but it is important to get the details right before scaling up.

The authors take issue with my work in the area for only looking at the direct effect of the carbon tax, and not a range of economy-wide impacts that then feed back into distribution:

Recent research in other contexts, however, has found that the incidence of energy and carbon taxes is dictated by general equilibrium responses and not well approximated by partial equilibrium studies such as Lee (2011) and Lee and Sanger (2008), which only consider the distributional effects resulting from households’ consumption of the taxed fuels and other carbon-intensive products.

It’s certainly an interesting argument, and they come up with a startling finding:

Using the model, we find that the existing BC carbon tax is highly progressive even prior to consideration of the revenue recycling scheme, such that the negative impact of the carbon tax on households with below-median income are smaller than that on households with above-median income. We show that our finding is a result of welfare effects of a carbon tax being determined primarily by the source of a households’ income rather than by the destination of its expenditures.

The model in question is a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model, which should raise some alarm bells. To assess the impact of trade agreements and tax changes, some economists have used CGE models, which develop a system of equations to model the economy, then shock it with a policy change to look at impacts once everything settles. Unfortunately, CGE is a deeply flawed approach that incorporates all of the market fundamentalism of neoclassical economics. Moreover, they give the appearance of making empirical estimates when really what is being generated is a function of the assumptions being made. Here’s The Economist magazine on problems with CGE models:

[T]he results of CGE models flow from the presuppositions of their authors. Most empirical exercises confront theory with numbers — they test theories against the data; sometimes they even reject them. CGE models, by contrast, put numbers to theory. If the modeller believes that trade raises productivity and growth, for example, then the model’s results will mechanically confirm this. They cannot do otherwise. In another context, Robert Solow, a Nobel prize-winner, has noted the tendency of economists to congratulate themselves for retrieving juicy plums that they themselves planted in the pudding.

In this particular paper, what assumptions are notable? “The model is based on the principles of general equilibrium theory. It combines microeconomic detail to project agents’ behaviour with the requirement of market clearing” and “Markets for all factors are assumed to clear perfectly (i.e., there is no friction in any of the factor markets). Labour is treated as mobile between sectors in each region but immobile between regions, as is conventional.” Also: “For each region and each sector, nested constant elasticity of substitution (CES) cost functions describe the price-dependent use of capital, labour, energy and materials for the production of commodities other than primary fossil fuels. Producers choose to substitute between different inputs (labour, capital, different types of energy and materials) to maximize profits.”

With those whoppers as starting points, they shock the model with a simulated carbon tax, then conclude on distribution: “To sum up, the progressive character of the carbon tax is mainly caused by the greater decline in real wages compared to the relative increase in real capital earnings. Households in the higher-income deciles are more dependent on labour income than households in the lower deciles, which means they are hit harder by the drop in real wages.”

So higher energy prices cause diminished economic activity and associated wage reductions, which disproportionately affect high-income earners, according to the model. For such a change in prices, however, it may also be the case that other low-carbon sectors are stimulated. Indeed, we know that capital investment in renewables generates more jobs per dollar as that invested in fossil fuels. And as a general note, there are both income and substitution effects for any price change, and these move in opposite directions. So it’s not obvious that the overall impact of a carbon tax is being modeled properly — there is a lot we do not know. But I suspect these results are an artifact of the assumptions in the model.

On the breakdown of income, transfer income is relatively more important to low-income households, capital income is relatively more important higher up the distribution. Some of the gain is attributed to transfer income being indexed to the CPI, compensating for higher energy costs. While this may be true for federal transfers like OAS and CCTB, it certainly is not the case for social assistance in B.C., a transfer most relevant to this analysis.

But the real distributional problem is on the expenditure side: it’s hard to get around the prima facie empirical case that low-income households spend a greater share of their income on energy, and therefore get hit with a higher share paid in carbon tax. This paper seems like a lot of hand-waving to me. Given the track record of CGE models, a quasi-empirical approach that is highly driven by the assumptions being made, I suggest some skepticism. And such a paper can be problematic to the extent that it endorses carbon-pricing initiatives that allow proponents to ignore distributional impacts.

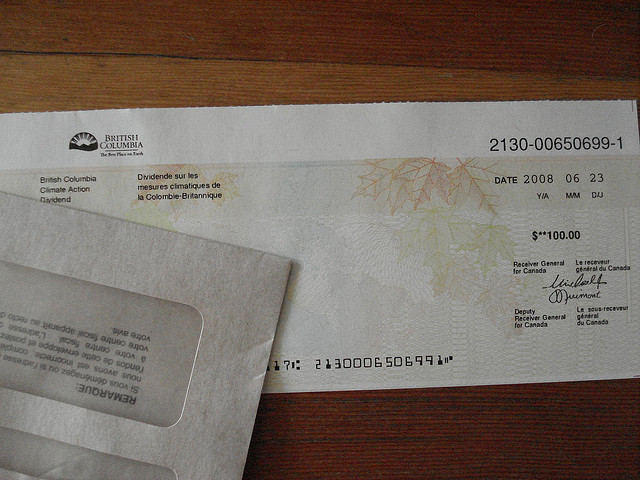

Photo: Rick Eh?/flickr