International trade started out simple enough. Countries exchanged various goods they couldn’t make themselves like silks, spices, sugar, and black people. But with the rise of huge multinational corporations, trade agreements have become incredibly complex, and also incredibly boring. Reading them is like staring at a magic eye puzzle made of words like “accordance” and “subcommittee,” and when it comes into focus you see Henry Kissinger’s face.

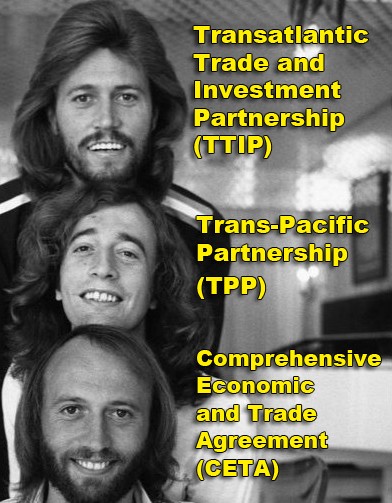

As a result they don’t get much play in the media (an exception being Glitter magazine’s “Which NAFTA Intellectual Property Clause Are You Crushing On?”) But it turns out these agreements have a powerful influence on our lives, so they’re worth understanding. Ones being negotiated now include:

These agreements have a couple of things in common:

First, they’re secret. Not to the hundreds of lobbyists and corporate lawyers helping to draft them, just to the normals. However, some drafts have been published by notorious internet prankster Wikileaks, who you might remember from the time they totally punked the U.S. military with this video. Come on MTV, give these guys a show already!

Second, each agreement contains a mechanism called “investor-state dispute settlement” (ISDS) which allows corporations to sue governments over laws that reduce their expected profits. Think of ISDS as an insurance policy that protects companies from catastrophes like floods of democracy.

To demonstrate exactly how messed up ISDS is, take the case of Philip Morris v. Australia. The company is suing the government for requiring cigarettes to be sold in plain packaging. If they win, that means brands legally trump votes. From there it’s a short, slippery slope to Emperor For Life Crunch.

Philip Morris tried to challenge these regulations in an Australian court and lost. But ISDS lets companies bypass domestic courts (notoriously biased towards laws and constitutions) and effectively turns a country’s justice system into the referee at a Harlem Globetrotters game.

The original aim of ISDS was to shield companies if a country seized their assets, like factories. But they’ve mutated into redefining regulations as theft. So now ISDS is used as a shield in the same sense that you use brass knuckles to shield your knuckles.

- Energy company Vattenfall is suing Germany for $5 billion after the government decided to phase out nuclear energy.

- Eli Lilly is suing Canada for $500 million for refusing to grant it a couple of drug patents, and oil and gas company Lone Pine is suing them for $250 million for Quebec’s fracking ban.

- Pacific Rim is suing El Salvador for $315 million for stopping a gold mine that threatened to contaminate water supplies.

- The Veolia group is suing Egypt for $110 million for increasing the minimum wage.

- Occidental Petroleum won a $1.8 billion settlement from Ecuador because they cancelled a contract Occidental breached.

- The Renco Group is suing Peru for $800 million for shutting down their metal smelter — among the most polluted sites in the world — and wants Peru to pay any damages due to 700 children poisoned by it.

Since 2000 the total number of ISDS cases has increased from 50 to over 500. It’s a growth industry created and fueled by corporate lawyers who help write the agreements, then use those same agreements to sue governments. They’ve basically designed their own Wheel of Fortune for their corporate clients to spin, and host the game like a soulless Pat Sajak (i.e. Pat Sajak).

Instead of slumming it in seedy courthouses, ISDS cases are presented before a posh, exclusive tribunal of three high-paid lawyers. And if citizens affected by the decisions try to testify or appeal, the bouncer will inform them they’re not on the list (but then let in like three hot corporations who say they know the DJ, which is such bullshit).

One tribunal judge said:

“When I wake up at night and think about arbitration, it never ceases to amaze me that sovereign states have agreed to investment arbitration at all.”

And then he shrugs and goes back to sleep on his gold-plated, Evian-filled waterbed, which he can afford with his $400 -$700 per hour wage. And at those rates, they have every incentive to drag cases out. For $700 per hour, a professional human centipedist would be begging for overtime. Unfortunately though, The United Human Centipede Workers union is suffering from historically low wages after many failed attempts at sit-down strikes.

Often just the threat of lawsuits is enough to make countries change course. A former Canadian government official had this to say about the effects of ISDS in NAFTA:

“I’ve seen the letters from the New York and DC law firms coming up to the Canadian government on virtually every new environmental regulation and proposition in the last five years. They involved dry-cleaning chemicals, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, patent law. Virtually all of the new initiatives were targeted and most of them never saw the light of day.”

To be fair, one of those environmental regulations was the infamous “Stand Your Soil” law that would have made it legal for trees to fire a gun in self-defense. Probably dodged a few literal bullets on that one.

For centuries people have fought and died to win basic human rights from their governments, but those governments are now falling over themselves to give away rights that aren’t basic or human, rights like “the right to a regulatory framework that conforms to a corporation’s expectations.” How is that a right?! No person has the right to have everything work out the way they expected. We wouldn’t grant newlyweds “the right to a marriage full of constant porn sex and no compromises.”

International trade isn’t an inherently bad thing. Most of us are cool with off-season fruit and Doctors Without Borders. But that’s not what all those WTO protestors are so angry about. What they and many others are against is turning corporations into a kind of super-citizen with rights beyond any mere mortal, who leaps domestic legal systems in a single bound and shoots streams of money and lawyers out of their nipples.

Because just like fictional superheroes, these very real super-citizens have expanded into a huge franchise, and as long as we tolerate them we can expect decades of shitty reboots.

This article first appeared on Medium.