Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Imagine going to a school that is broken. A school that sits on a toxic field of noxious fumes that makes you and your classmates sick.

Then, the government continually breaks its promise to build a new school and you and your classmates are left to sit in makeshift portables in 40 below weather, where the doors and windows don’t shut properly.

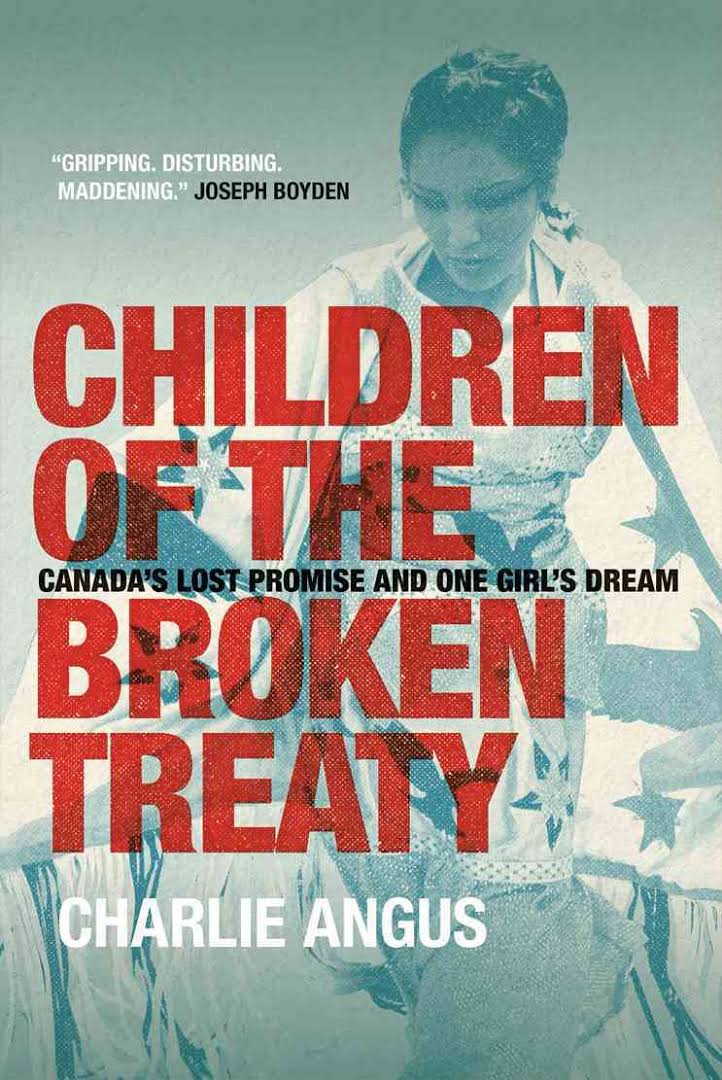

This was the reality for students of J.R. Nakogee Primary School in the village of Attawapiskat in Ontario, which is expertly detailed in Children of the Broken Treaty: Canada’s Lost Promise and One Girl’s Dream by Charlie Angus.

Angus addresses the legacy of Shannen Koostachin and the trail of broken promises left by the government beginning with the assimilationist policies of John A MacDonald up to the neglectful policies of today.

A history of neglect in Attawapiskat

In 1976, the J.R. Nakogee Primary School opened to great hope for change in the Treaty 9 territory. Families were excited about the primary school because it meant they could be involved in their children’s development.

From the beginning, the J.R. Nakogee school was bare bones compared to other schools being constructed in the rest of Ontario. However, to the parents in Attawapiskat — who had suffered through the notorious St. Anne’s Residential School — it was everything they could wish for because it meant that their children could stay in their community and not be taken away like they had been during the residential school era.

During the early 1980s students and teachers began to complain about headaches, nausea and other ailments. It was found that while digging to make an extension to the school that leaked fuel was discovered.

In 1984, the Department of Indian Affairs sent in a team to assess the situation. Band-aid solutions were made but 12 years later in 1996, the damage was done — diesel fuel heavily saturated the grounds in which J.R. Nakogee School sat.

On May 1, 2000, the band council of Attawapiskat condemned the school and ordered it closed. Pressured to act, the Department of Indian Affairs agreed to set up seven duplex portables with another portable complex for band administration. However, they were set up adjacent to the contaminated site and “dust from the contaminated site blew into the portables and surrounding playing field.”

Soon after the school closed, Minister of Indian Affairs, Robert Nault attended a meeting with the chiefs of the Mushkegowuk Tribal Council which represented the James Bay communities. The council was told “There will be a new school built. It will go ahead and we will do everything to make it happen.”

But that promise fell through. The regional director of Indian Affairs at the time said “despite Nault’s promise, it would take at least 10 years for Attawapiskat to see a school.”

Hence, the waiting began. The school that had brought much hope to the community was now abandoned and it posed serious health concerns for the children being educated in its shadow.

Koostachin and Angus bring hope and real change

In 2004, Angus was elected as Member of Parliament in the riding of Timmins-James Bay. “At the time, I knew very little of the history of Treaty 9 which covers the vast majority of the constituency,” he writes.

“On my first trips to James Bay, I realized how development in the region was being hampered by a series of interrelated crises in infrastructure. Not only were housing, water treatment and education badly underfunded, but also there were no enforceable standards for ensuring public safety,” writes Angus.

“Unlike provincial jurisdictions, the reserves are under the Indian Act, and there are no legal benchmarks for ensuring safe water, adequate building construction, fire protection, health services, child welfare and of course, educational outcomes.”

Shannen Koostachin, a grade 8 student at the time, realized the chronic underfunding of First Nations schools by the government and in response helped launch the Students Helping Students campaign aimed at standing up against Canada’s entrenched system of “educational apartheid” and getting a school built in Attawapiskat. She found a powerful ally in Angus, whose life she would change indelibly.

The campaign gained momentum and raised awareness about the systemic inequalities faced by the children in Attawapiskat and First Nations communities in Canada.

And, in December 2009, it was announced that a new school would be build.

A must-read for all Canadians

Koostachin wanted the decent education that she deserved and she fought hard for it. Her fight shined a light on the many injustices suffered by many generations of children.

Koostachin was killed in a car accident in 2010, not long after the government announced the building of a new school in Attawapiskat. Her death had a huge impact on her community and also galvanized the resolve of a larger activist movement that had seen her as an emerging youth leader.

To carry on Koostachin’s fight and legacy, the Shannen’s Dream campaign was launched to fight for equity for all First Nations youth.

The Children of the Broken Treaty is an incredibly important book. At times it is difficult to read — it really makes your blood boil at the injustices the Treaty 9 people have had to endure.

If you think that all Canadians are treated equally, Angus’ excellent job in detailing the history of the Treaty 9 area makes you see otherwise.

Canada should be ashamed of the way it has treated the children of Attawapiskat, the people of Treaty Number 9 and Indigenous people.

.

Christine Smith (McFarlane) is a Saulteaux First Nations woman, who hails from Peguis First Nation. She is a published writer and freelance writer for Anishinabek News on a regular basis. She has also contributed to other newspapers such as the Native Canadian,The Native Journal, Windspeaker, New Tribe Magazine, and FNH Magazine. She is a contributing editor with Shameless Magazine, and a contributing writer for the Toronto Review of Books.