Noopiming, the Anishinaabemowin word for “in the bush,” isn’t the bush 19th-cenutry white settler author Susanna Moodie was roughing it in. Or maybe it is, and she just wasn’t able to see it through an Anishinaabe worldview that is highlighted in Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s response to Moodie’s 1852 memoir Roughing it in the Bush.

Simpson is an award-winning Nishnaabeg storyteller who hails from Alderville First Nation, which is located in Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg territory, also known as the Kawartha Lakes. In her new novel, she transports you into a world filled with spirits, animals, humans and ancestors who are all in relationship to one another. Here, you will meet an old man fighting the changing times to share ceremony with a new generation. A recovering alcoholic walking the red road and relearning the joys of a sober life. You will also find a hoarder who loves a good deal and an old friend who finds peace in the bush amongst the spirits. Each character has their own story, voice and world view, different and similar all at the same time.

The book starts with the narrator, Mashkawaji, frozen and suspended in a lake. Through song and thoughts, the reader is taken through the feelings of being frozen beneath a lake’s surface. Though they are restrained, there is a sense of freedom in their words that convey their circumstance isn’t as unfortunate as you may have believed. The chapter ends with the introduction of six more main figures in the novel, each connected to the being frozen in the ice: Akiwenzii, Ninaatig, Mindimooyenh, Sabe, Adik, Asin and Lucy. Their stories are seen as absolute truth, as it is repeated over and over again that the narrator will believe everything these seven say. Very rarely throughout the book will you find a page filled from top to bottom. Instead, Simpson uses short passages to convey the feelings and actions of each character.

Mindimooyenh is quick-lipped and ready to tell you how it is, never holding back their opinion or two cents. Throughout the novel they pose as an eccentric hoarder, advice-giver and unofficial pharmacist for Black and Indigenous peoples in need of medical supplies. The narrator also discusses the effects that the United States’ violent detention of migrants and their children is having on Mindimooyenh: “Every time ICE rips another family apart, their body produces slightly less melatonin because there is slightly less light.” Mindimooyenh is also passionate about Palestine, repeating that Palestinians are their “cherished relatives.”

Ninaatig and Akiwenzii are old friends connected through childhood memories and adventures, while Asin and Lucy are trying to learn the traditional ways of the Anishinaabe, through ceremony, songs and land-based learning. Sabe is on a journey of healing after getting back on the wagon, though they’re not the only one. Each character goes through their own form of healing by themselves and through and their relationships with each other.

The novel is cleverly written in a way that leaves the reader unsure of who is a human, an animal or a spirit. Each character could be one of the three or a combination of all. Simpson’s use of Anishinaabemowin throughout the novel both through the names of the characters and conversational pieces helps to elevate this mystery. For a reader who is not familiar with the language, one would not know that Adik means reindeer or Asin means stone. Even with knowledge of the Anishinaabemowin language and storytelling, it is on the reader to find out just who everyone is or could be.

Set in Toronto, Peterborough and the Kawartha Lakes, the novel connected me back to all three places but in particular the Kawarthas. I have spent time on the water in places like Pigeon Lake, so Simpson’s novel easily transported me back to my childhood. Much like Mindimooyenh, I spent nights dreaming of houseboats as they sailed along the water. While away at university in Peterborough, like Lucy I escaped to the big city on the Go Train or Greyhound. The chapters about Mandaminaakook and Shkaabewis remind me of stories and teachings of the geese that I learned from my Elders.

While Moodie’s Roughing it in the Bush leaves a bad taste in your mouth with her racist interpretations of the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg, Simpson expands your palate to include a more holistic understanding of kinship to all beings and relationships to land. This is not the rough and unforgiving landscape from the colonial memoir you might remember but instead is a place filled with life, love, anger and healing.

Noopiming is exactly what its subtitle says it is supposed to be: The Cure for White Ladies. It is a healing journey of Indigenous futurism through poetry, song and storytelling. The novel makes commentary on real world issues and humanitarian crises. Taking traditional Anishinaabe teachings and weaving them through contemporary forms of understanding. Simpson brings the reader into not a new world, but a world already existing, one that breaks through the colonial bars that try to cage it.

Shanese Indoowaaboo Steele is an Afro-Indigenous writer and activist and can be found on Twitter at @gagiibaaikwe or on Instagram @shaneseanne.

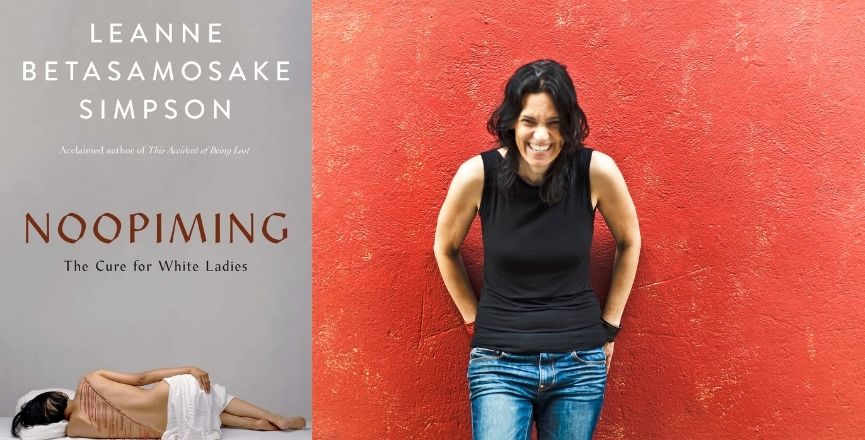

Author image: Nadya Kwandibens/Red Works Photography