Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

“Indeed, much of what we learn about history in school, at the movies or on the History channel revolved around the lives of individuals with the most money and power in society, such as monarchs, capitalists, and politicians. But workers’ lives matter too; without our labour, society would cease to function. We are important agents of social transformation, and our power is magnified when we work together.”

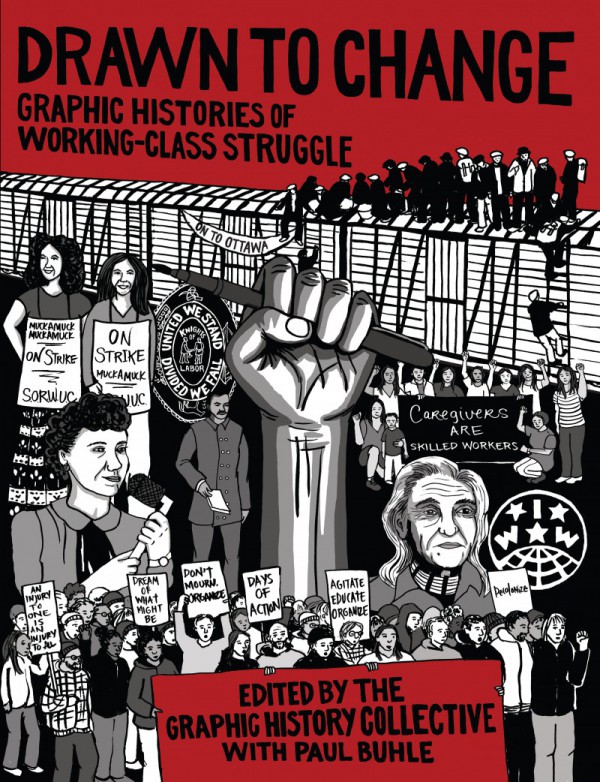

So begins the Graphic History Collective’s new collection Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working Class Struggle.

Drawn to Change has over 20 contributors with nine comics portraying different moments in Canadian labour. From 19th-century Knights of Labour to the contemporary Live-in Caregiver Program, this collection of chronological graphic histories is a feat of visual expression and storytelling and an incredible resource for Canadian labour history.

The medium is a key aspect of the collection’s importance and success. By engaging artists to create graphic histories based on the stories of their families, community members and comrades, this book opens the door to active, artistic and ongoing knowledge production about labour stories.

As a whole, Drawn to Change depicts more than just stories of labour activism. It is a resource for understanding the evolution of Canadian labour.

It starts with the roots in the late 1800s factories illustrated by”Dreaming of What Might Be: The Knights of Labor in Canada, 1880-1900″ and moves on to stories like Bill Williamson’s journeys across the country — and the world — in “Bill Williamson: Hobo, Wobbly, Communist, On-to-Ottawa Trekker, Spanish Civil War Veteran, Photographer” and eventually nears the end with stories about now-defunct labour organizations like SORWUC in “An ‘Entirely Different’ Kind of Labour Union: The Service, Office, and Retail Workers’ Union of Canada.”

This book offers an incredible insight into the ups and downs of the Canadian labour movement over the last 150 years through moving personal stories and individual accounts.

I was entirely consumed and invested in the fates of the “characters” throughout the book.

I was nervous for the divided unions during the 1990s Ontario Days of Action in “The Days of Action: The Character of Class Struggle in 1990s Ontario.” This “action-packed” story follows the rise and fall of labour organizing that was deeply connected with provincial politics of the time and exacerbated by divisions within the labour movement.

The stories are a historical — not to mention emotional — rollercoaster, even despite the fact I already knew the outcome. I was hopeful after the NDP’s 1990 election win and crushed with Bob Rae’s regressive labour legislation. I cheered for the workers during the many days of action during the 1997 teachers’ strike and was deeply disappointed when union leaders broke ranks to negotiate with Mike Harris’ Conservative government.

In the most contemporary story, “Kwentong Bayan: Labour of Love,” I sympathized with the complicated relationships experienced by long-term caregivers in Canada.

The contributors illustrated the tough questions these workers grapple with: How do you reconcile yourself with an oppressive boss when you’ve grown to love their children? How do you deal with the loneliness and isolation of having to live with at work in a foreign country and not grow bonds with your charges?

While these are only two examples, all the stories are vivid and relatable and told in earnest and with care. At some moments, I was also just struck by the beautiful graphics and their emotive power.

And more than moved by great storytelling and powerful art, I was spectacularly informed.

This book does not sweep anything under the rug and is critical of any exclusion based on race, gender or other social markers,

For example, taking labour history head on, the experience of Asian workers is addressed in “Dreaming of What Might Be: The Knights of Labor in Canada, 1880-1900.” Though the Knights of Labor were foundational activists in the Canadian labour movement, the authors credit their pioneering actions and criticize their anti-Asian stance.

They also acknowledge the different experience of racialized workers when they describe that Asian workers sometime had to take work as scabs replacing striking workers because of their “dire economic circumstances.”

Inadequate labour leaders, “pink” unions and organizational failure to follow through with community momentum — all shortcomings of the Canadian labour movement — are candidly described.

What sets this book apart is the description of the “Canadianization” of labour and how it both positions these Canadian histories on the international stage and highlights the unique aspects of our labour movement’s history.

The relationship between work and resistance by Indigenous longshorers in British Columbia in “Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet” teaches us about the development of the sawmill industry in B.C. and the indispensability of the Coastal Salish people to the work.

Despite being highly skilled workers, Squamish longshoremen faced racism and discrimination, leading them to establish their own union. At the same time as organizing to resist poor conditions in the workplace, the wages they earned provided resources for community leaders to travel to Ottawa and the United Kingdom to discuss land policy.

The only drawback of this anthology is it lacks more stories about Indigenous workers, workers of colour, queer workers, differently abled workers and other minorities.

However, this shortcoming is plainly addressed by the Graphic History Collective in the introduction: “These individual stories, though, only offer readers snapshots of a more fluid and complicated history of working-class struggle in Canada.”

They encourage readers to create more comics and tell more stories to paint a better picture of Canada’s diverse, complex and distinctive labour history. “For now, we hope these comics generate new interest in labour and working-class history and demonstrate the importance of learning from the past, as a resource, to help guide present and future struggles for social change.”

Drawn to Change is a comprehensive historical account that easily outshines other labour history texts because of its progressive self-reflection and grassroots feel.

Woven through all the pieces is a very palpable sense of hope. The stories that had union leaders breaking ranks, police violence and even war were somber at points, appropriately grave in their description of labour struggle.

This distinctly Canadian collection is an invaluable resource that should be utilized by both labour educators and history teachers. This accessible, artistic anthology has a place in the libraries of activists and organizers as well as in public school classrooms.

Haseena Manek is a freelance writer, editor, photographer and radio journalist. Co-writer and editor of Media Works: Labour Rights and Reporting Handbook. Follow her on Twitter here.