In the hyper-polarized context of Canadian energy policy debates, even suggesting that there might be a downside to the untrammeled energy boom centred in northern Alberta is enough to get you labelled a traitor or an economic illiterate — or both. Conservative political leaders in both Ottawa and Edmonton, backed by energy-friendly think-tanks and the Sun media chain, have tried to paint such thinking as idiotic and dangerous, not deserving of serious consideration. This is a distinctly McCarthyist strategy: it relies on vilifying and marginalizing opposition, rather than debating facts and arguments.

Former Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty, daunted by this firestorm, censored himself quickly after wading into the debate (even though there is no empirical evidence that what he said — namely that Ontario was suffering damage from oil-driven currency appreciation — was wrong). NDP Leader Tom Mulcair has certainly toned down his own interventions in this debate, while carefully continuing to make the (reasonable) point that more careful management of the bitumen boom would reduce its costs and enhance its net benefits (both economic and environmental). Bitumen advocates and lobbyists hope they’re successfully silencing these and other critiques through the sheer intensity of their self-righteous outrage, if nothing else.

But what do the actual facts indicate? Bitumen boosters like to pretend there is a “consensus” among hard researchers that the Dutch disease hypothesis is false. For example, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Philip Cross recently stated bluntly in the National Post that “the notion of Dutch disease … has been so discredited that even politicians shy away from its use.” [As noted, politicians may shy way from saying something, even if it’s true, for political reasons, not because of any lack of veracity.] Some reporters have echoed this theme that empirical research has somehow refuted the deindustrialization concern. For example, Shawn McCarthy wrote a very fair article in the Globe and Mail on the release of the CCPA’s recent study The Bitumen Cliff: Lessons and Challenges of Bitumen Mega-Developments (of which I was one of four co-authors); he noted that our report faced an uphill struggle to “rebut a long series of studies from business economists who dismiss the so-called Dutch disease.”

Many Canadian policy researchers have indeed weighed in on the “Dutch disease” issue over the last year or so, spurred by the loud public debate over the possible side effects of the bitumen boom. Have all these studies in fact disproved the hypothesis that surging energy exports, via their impact on the exchange rate (and perhaps through other channels), has damaged prospects for Canadian manufacturing and other non-resource export industries? An interesting part of my contribution to the Bitumen Cliff was in fact to survey the extant literature on the matter, which is summarized with annotations in Appendix 1 of the report (pp. 73-87). If I do say so myself, I think that Appendix is worth the price of admission for the whole study (actually, the study is available for free, of course … like all CCPA studies at policyalternatives.ca). In fact, the overwhelming weight of empirical evidence confirms that surging oil prices and exports have indeed contributed to the rise of the Canadian dollar, which in turn has indeed contributed to the decline of Canadian manufacturing.

First, let’s quickly shed some straw men. The fact that Canada’s experience today is very different from the Netherlands’ in the 1970s doesn’t prove or disprove anything. The hypothesis is not that Canada is suffering exactly what the Netherlands experienced. The hypothesis is that resource exports, via the exchange rate, are indirectly damaging other exports (especially manufacturing) — a chain of causation commonly known (rightly or wrongly) as “Dutch disease.” In fact, I would suggest that there are several factors which mean that this problem (if it is a problem) is likely far worse in Canada’s case, than it was in the Netherlands:

– There’s a lot more energy to export from Canada, and the energy boom is likely to last longer.

– Canada’s regional differences make it much harder to reallocate real inputs to energy production and export from manufacturing and other shrinking sectors.

– The Netherlands operated within a pre-EMS exchange rate regime (in which their central bank broadly pegged their currency to the German mark) which helped to shelter that country from some of the side effects of resource development.

There are many other countries in the world which have experienced similar pressures arising from rapid export-oriented resource developments. I would prefer to shed the term “Dutch disease,” and use the more generic moniker “resource-driven deindustrialization.”

Second, no one that I am aware of (myself certainly included) has ever claimed that oil prices were the only cause of the rising dollar, nor that the resulting appreciation has been the only problem besetting Canadian manufacturing and other tradeable sectors. There are other reasons why manufacturing employment and production have declined in Canada, including:

– The 2008-09 recession in the U.S. and other key export markets.

– Globalization through which production from other jurisdictions (including especially China) has displaced Canadian-made output at home and abroad.

– The fact that productivity growth is faster in manufacturing than other sectors. (This helps explain why manufacturing employment might decline as a share of total employment, but not necessarily in absolute terms; it also does not explain why manufacturing output would decline in either relative or absolute terms.)

– The fact that the income elasticity of demand for most manufactures is less than unity (and hence that consumers prefer proportionately more services, and proportionately less merchandise, as their incomes grow). (This helps explain why manufacturing output might shrink as a share of total GDP — but not why it would decline in absolute terms.)

The latter two points are often invoked to explain why manufacturing has declined as a share of total employment or total GDP in virtually all countries — and so why should Canada be any different? (The prolific blogger Stephen Gordon showed a graph of this universal decline to suggest sarcastically that the problem should be called “global Dutch pandemic,” not “Dutch disease”). But neither of those structural features of manufacturing can explain the precipitous decline in absolute employment and GDP in Canadian manufacturing since 2002 — nor why the relative decline has been much worse in Canada during that time (and left our manufacturing smaller as a share of the total economy) than in virtually any other advanced economy. Real absolute value-added in Canadian manufacturing peaked in 2000, and is currently 15 per cent lower than that peak (despite a partial recovery since 2009). Absolute employment in manufacturing is down by one-third in the same period — only partly reflecting productivity growth, and mostly driven by the decline in absolute output. And Canada’s trade balance in manufactured goods went from approximate balance in 2000, to a nearly $100 billion deficit today. So this is not a problem mostly rooted in the shrinking relative importance of manufacturing in general over time. It is mostly a problem of consumers (both at home and abroad) not wishing to buy Canadian-made manufactures, and in that context the issue of the loonie’s decade-long appreciation (beginning in 2002) is clearly relevant.

For my work on Bitumen Cliff’s Appendix 1, I surveyed 9 previously published studies and reports, from a range of governmental and non-governmental sources, that touched on the issue of the side effects of the bitumen boom on the rest of Canada’s economy (and in particular on other tradeable industries — including manufacturing, but also including other non-energy merchandise, tourism, and tradeable services, all of which have also declined, relatively and in many cases absolutely, during the course of the bitumen boom). Since the Bitumen Cliff came out two weeks ago, one more study can be included in that set: the IMF’s annual report on Canada’s economic prospects, the so-called “Article IV” consultation, available here. (I am grateful to David Crane for drawing that one to my attention: this report should have received a lot of media coverage in Canada, but was largely ignored.)

To argue that overexpansion of resource exports has squeezed out non-resource tradeable industries (especially but not solely manufacturing) via the exchange rate, two distinct sub-hypotheses must be sustained:

1. The rapid current and expected expansion of energy exports (associated with, and driven by, high commodity prices for those exports) must explain (at least in part) the appreciation of the Canadian dollar.

2. The appreciation of the Canadian dollar must explain (again, at least in part) the contraction (in relative and often absolute terms) of production, employment, and exports of non-resource tradeable industries.

Once again, energy exports and prices don’t need to explain all of the appreciation of the dollar, which in turn does not need to explain all of the decline in other export sectors, for the hypothesis of resource-driven deindustrialization to be supported by the data. Now, in my day-to-day experience as a policy economist, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone from the Canadian financial community who would disagree with sub-hypothesis No. 1 (namely, that oil has at least something to do with the loonie’s rise since 2002). And I don’t think I’ve met anyone from the manufacturing sector who would disagree with No. 2 (namely, that the 60 per cent appreciation of the Canadian dollar since 2002 has at least something to do with the dramatic downturn in Canadian manufacturing during that same time). Put those two fairly self-evident propositions together, and you have a case for the existence of resource-driven deindustrialization. But the uncomfortable political consequences of that seemingly obvious conclusion have led defenders of the bitumen industry to claim, in loud and self-righteous voices, that this argument is somehow ridiculous.

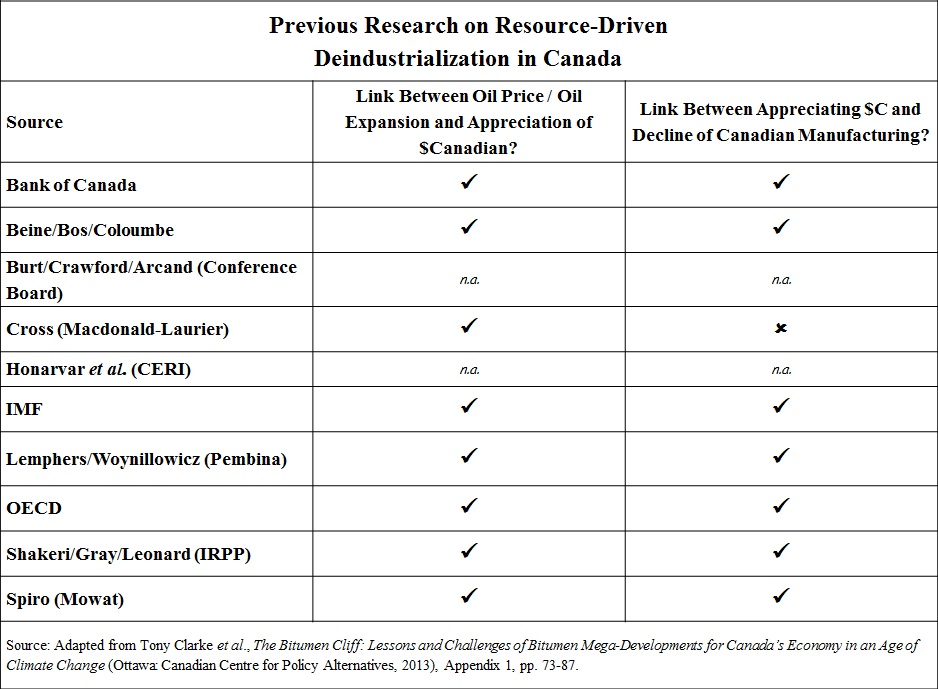

The above chart summarizes the analysis provided by each of these 10 studies, regarding each of those two links in the logical chain required to sustain a resource-driven deindustrialization hypothesis.

Two of the oft-cited reports (from CERI and the Conference Board) are silent on both components of the deindustrialization hypothesis. They rely on input-out data (from 2006 for CERI, and 2008 for the Conference Board) to estimate the economic spillovers from bitumen developments to other provinces. Both assume a constant exchange rate (and hence do not even consider whether “Dutch disease” exists, never mind refuting it). Both find that spillovers to other provinces are actually very small (relative to ex-Alberta Canadian GDP and employment, and also relative to the much-larger spillover benefits that both studies report are captured by the U.S. economy); however, if you add up small effects over many years, you get numbers that “seem” large, and that’s what coverage of these findings has focused on. See Appendix 1 of The Bitumen Cliff for more details on the methodology and findings of these two reports. I have assigned them “n.a.” in the table above, since neither report actually addresses the twin issues at stake.

Seven other studies listed in the table provide original empirical analysis confirming both that the run-up in oil prices (and associated expansion of Canada’s petroleum industry) is indeed significantly associated with the post-2002 appreciation of the Canadian dollar, and that that appreciation was a significant factor in the erosion of Canada’s manufacturing sector (variously measured — in absolute terms, as a share of Canadian GDP, as a share of U.S. manufactured imports, and so on). This includes the twin speeches last year by Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney — which were widely interpreted as refuting “Dutch disease,” even though the empirical analysis he cited confirms that it exists. (See my previous post on this “spinning” of Mr. Carney’s remarks.) It also includes official reports from both the OECD and the IMF: both agencies viewed both sub-hypotheses as largely non-controversial, and confirmed them with their own analysis. The IMF report contains an intriguing reference (in paragraph 21, page 16) to efforts by Canadian officials (sensitive to the politics of these findings) to dissuade the IMF from their view. Other research that has confirmed that oil helps explain the dollar, and the dollar helps explain the decline of manufacturing, include reports by Serge Coulombe and colleagues, the IRPP, and the Pembina Institute. Not listed in the chart above, of course, are the findings of The Bitumen Cliff itself, which also confirmed a strong link between oil prices/exports and the Canadian dollar, and a strong link between the overvalued currency and Canadian deindustrialization. (Counting our own study, then, there are at least 8 reports supporting both sub-hypotheses with original analysis.)

There is only one “X” in the entirety of the research summarized in the table above, relating to Philip Cross’s report for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. First Mr. Cross reviews previous research on the determinants of the Canadian dollar’s appreciation (including other studies listed in the table above), and argues these studies find that commodity prices are a “secondary factor” in the dollar’s strength. I do not think that is a correct summary of those studies: in fact, they ascribe as much or more importance to commodity prices as any other single factor. (Just because an explanatory variable explains less than 50 per cent of the change in a dependent variable, does not make it a “secondary” factor; so long as there are more than 2 explanatory variables, it could indeed still be the most important causal factor.) Mr. Cross concludes that “it is erroneous to attribute all of the decade-long strength of the Canadian dollar to higher commodity prices.” Yet that extreme view which he refutes is both a straw man, and unnecessary to sustain the deindustrialization hypothesis. You merely need to conclude (as Mr. Cross himself does) that energy prices have been a measurable cause of the dollar’s strength, to then go on to test the second sub-hypothesis in the logical chain.

On that second sub-hypothesis, Mr. Cross breaks from the rest of the research and denies that the strong dollar is associated with the decline of Canadian manufacturing. In fact, he goes further to deny that any such decline has in fact occurred. He measures the well-being of the overall manufacturing sector by its nominal sales; overall nominal shipments in 2011 were about the same as they were in 2002, and there are several sectors which have experienced growing nominal sales during this time, in addition to those which have experienced falling nominal sales (exactly what you would expect in a heterogenous category with statgnant overall nominal sales). On this basis he concludes that Canadian manufacturers have successfully adapted to the high dollar — in part, he suggests, by reducing exports and increasing their imports of imported intermediates. This analysis is novel: most analysts would measure the success of manufacturing not by nominal sales but by real output and/or employment (both of which have declined sharply during the last decade), and most analysts would interpret falling exports and growing imports as symptoms of weakness in manufacturing (not signs of successful adaptation).

The key point here is not to refute Mr. Cross’s conclusions (see Appendix 1 of The Bitumen Cliff for more detail on that), but rather to point out that with that one exception, there isn’t a single piece of published research I am aware of that has empirically refuted either of the two sub-hypotheses defined above. Far from being “discredited” by empirical research, the resource-driven deindustrialization hypothesis is almost universally supported by it.

Now, agreeing that strong oil prices and oil exports explain at least some of the rise in the Canadian dollar, which in turn explains at least some of the contraction in Canadian manufacturing, does not mean there is nothing left to debate. Far from it. Additional points of controversy, on which there is clearly no consensus in the above literature, would include:

1. How important has resource-driven deindustrialization been relative to other factors affecting manufacturing and the overall Canadian economy?

2. Have the economic benefits of resource extraction and export outweighed the costs of resource-driven deindustrialization?

3. What, if anything, should policy-makers do to offset or reverse resource-driven deindustrialization?

In this context, the debate is not over whether resource-driven deindustrialization exists, but over how important it has been, whether its costs are offset by the benefits of resource expansion, and whether government and the Bank of Canada should do anything about it. That’s a far more nuanced, interesting, and productive set of questions to consider (I have my own views on each point, of course), compared to the sarcastic McCarthyism which typifies so much previous commentary on these matters.

Jack Mintz (U of C School of Public Policy and a Director of Imperial Oil) is hosting an interesting session in Toronto later this week on Dutch disease issues. One panel is titled “The Myth of the Resource Curse,” which gives a little advance sense of where the event’s planners are coming from. The list of speakers includes prominent Dutch-disease deniers like Mr. Cross and Mr. Gordon; but it also includes Mr. Coulombe, whose research clearly proves that resource-driven deindustrialization has occurred. The concluding panel has a more neutral title: “Potential Policy Responses: What Are They, and Are They Necessary.” Hopefully this indicates a willingness to engage in debate over the issues, rather than an attempt to squelch it. I have registered to attend, in hopes of pursuing a more genuine dialogue on these matters than has prevailed so far.

Jim Stanford in an economist with CAW.