Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Right now there are a handful of ways to get our ideas out of our heads and into our computers. We can type, record audio, take pictures or videos, dictate for text conversion, send emoji, or make notes and diagrams with styli.

Our input methods have improved remarkably over the decades. Our first interactions with computers were via patch cables and switches. Then we moved to close-to-the-metal machine language codes, punch cards and text-only terminals.

But it wasn’t until the mid-’80s that the average computer enthusiast could start toying with voice input, styli and touch pads, and crude, low-resolution images. Back then, even MIDI, a now-ubiquitous way of controlling digital instruments, was a hobbyist’s pastime.

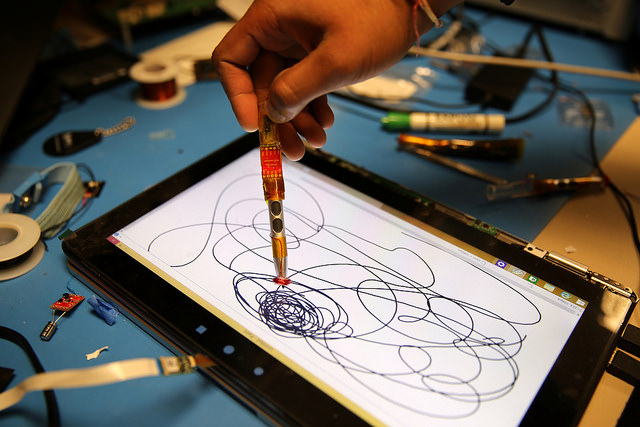

But in the last decade, the floodgates have opened. Voice recognition, a formerly frustrating hit-and-miss affair, has gotten so good so fast we are starting to take it for granted. Stylus input on tablets and smartphones is reliable. Smooth handwritten notes and diagrams are as fast and accurate as ink on paper using pressure-sensitive devices like the Microsoft Surface tablet and the most current iPads.

And, it is an odd mobile device indeed that can’t record stills, audio and video, and insert them into all manner of documents or send them wireless.

There is, of course, room for improvement and innovation. For example, we still don’t have seamless interaction between the different ways we interact with our devices. We can’t point to, or look at, something on a screen and say, “put that here” or “define this.” We can’t have real, idiomatic conversations with autonomous software agents.

The tactile feedback we get from our screens is just a notch above a joy buzzer. 3-D gestural input for virtual and augmented reality is in its infancy and the research into controlling computers or even the servos in artificial limbs with our minds is embryonic.

But still, the rate of input development is outstripping the implementation, research into it and the interfaces that make use of it. 3D Touch on the iPhone is a great example of this. The “pop” and “peek” gestures it enables have been unevenly adopted by software developers and have elicited confusion in users. Virtual keyboards on most mobile devices sport a bewildering variety of key arrangements and input methods — swipe, autocorrect, typing, emoji input, etc. Even the responsiveness to stylus input varies not only from device to device but from app to app on the same device.

And, as a recent study by two researchers at Princeton suggests, academics are still creating an artificial divide between analog and digital input. The study compared the information retention of students who took handwritten notes compared to those who took notes on a computer via typing. However, a lot of students are now taking handwritten notes on tablets. The false dichotomy of input on paper vs. input on keyboards highlights how fast the landscape is changing.

We don’t really know the best way to interact with our machines, nor the best ways for them to interact with us. We are in the “uncanny valley” where we are close to engaging with our devices more organically, but still fall back on the typewriter, the pointed charcoal stick and a screen the size of a sheet of paper. These are, of course, the limitations of our hands, our imaginations and our devices. There will have to be better ways soon, not because we will demand them, but because our machines will become impatient of our scrawlings, gestures and our words crawling towards them one character at a time.

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a long-time writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.

Listen to an audio version of this column, read by the author.

Photo: Intel Free Press/flickr

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.