Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

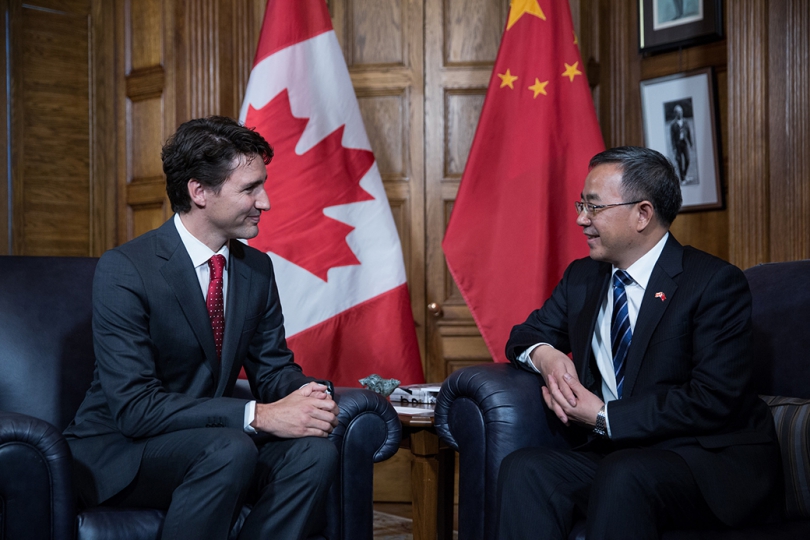

Prime Minister Trudeau leads a big entourage to China this week, in hopes of expanding Canada’s foothold in that huge economy. A couple of interesting media stories set the stage for the visit: an overview of China’s evolving diplomatic and economic strategies by Andy Blatchford of Canadian Press, and a review of China’s growing emphasis on migrant labour provisions in trade deals by Jeremy Nuttall in The Tyee.

I recently compiled some data on Canada’s present highly lopsided economic relationship with China. Here are the main features of our current, unbalanced relationship.

Canada’s trade with China is lopsided: Quantitatively and qualitatively.

Whenever someone says we should “trade more” with China, we have to ask: “What kind of trade? And going in which direction?” Achieving “more trade” hardly helps Canada, if that trade consists mostly of imports. And that has been increasingly the case in recent years.

The bilateral trade flow was broadly balanced until the mid-1990s, with a modest flow going in each direction. But then China’s export-led industrialization strategy kicked into gear, and China’s exports then took off: first with a heavy reliance on simple labour-intensive manufactures (rooted in China’s abundant, then-low-cost labour force). Close state oversight of trade flows meant that imports did not respond accordingly, and China began to generate very large, sustained trade surpluses.

Canada developed a large and chronic trade deficit with China, that really exploded after the turn of the century: quintupling between 1999 and 2008, reaching over $30 billion. It paused for a few years after the global financial crisis.

But since 2013 the deficit has surged once again. From 2012 through 2015 Canada’s exports to China grew hardly at all: by less than $1 billion. But imports from China grew by $15 billion. The bilateral trade deficit has thus swollen by half in three years, reaching $45 billion last year — an all-time record, and Canada’s largest bilateral imbalance. (Mexico is next biggest, at barely half that: a deficit of $24.6 billion.)

Canada-China bilateral merchandise trade balance

Services trade between the two countries is much smaller, and almost perfectly balanced: just over $2 billion going each way. That’s better than the huge lopsided deficit in merchandise trade. But the idea that services exports by Canadian firms can somehow make up for the flood of merchandise imports coming in from China is not credible. The scale of merchandise imports, and its one-way nature, is a completely different order of magnitude than our relatively balanced and modest services trade.

In sum, Canada imports about $3.25 from China for every dollar worth of exports we sell there.

Our resources for their manufactures

Canada’s imports from China consist almost entirely of manufactured goods. Our exports to China are roughly half manufactured goods, and half resource products. And of the manufactured goods we export, there is a heavy concentration on basic industrial goods (like basic metal ores, which show up in the data as a “manufactured” product, but are still clearly resource products).

Canada’s top five exports to China (at the four-digit product code level) in 2015 were (in order): pulp, canola, lumber, copper and potash.

Our top five imports were telephones, data processors, automotive parts, toys and seats.

In essence, we export raw materials to China, which are manufactured into value-added products, and sold back to us — and in much greater quantity, to boot. So the structural underdevelopment which characterizes our general global trade, being increasingly pigeon-holed as a resource supplier, also describes our relationship with China. Since China is an emerging economy, and we are supposedly “high-skill and capital-intensive,” this is both surprising and worrisome.

Moreover, the stereotype of China as an exporter of cheap labour-intensive goods is increasingly inaccurate. The Chinese industrial development strategy is focused heavily on moving “up the value chain.” Through a range of policy measures, including state-directed investment, requirements for technology transfer on the part of incoming foreign investment, an aggressive and well-funded higher education and research agenda, and the promotion of concentrated “national champion” companies with a global focus, the government is successfully transforming the country’s role in international trade into one that is increasingly high-technology and innovation-based. At the same time, the steady rise in Chinese wages and living standards (also part of the state strategy) means China is not especially “cheap” anymore from a labour cost perspective. Indeed, wages in Mexico in most sectors are lower than in the industrial areas of China.

The heavy role of active state policy in setting the course of China’s economy means it’s a misnomer to speak about “free trade” in this context. Government policy there will continue to effectively limit imports except in areas where they want and need imports. That includes high-tech machinery and equipment (which they buy in large quantities from Germany, the U.S., and a few other countries — but hardly at all from Canada) and natural resources (in cases where their domestic supply, always their first-best option, is inadequate).

Incredible as it may seem, therefore, Canada is playing an increasingly subservient role in trade with China: supplying them with resources, accepting their imports without limit, and accepting increasing amounts of Chinese FDI (mostly in resource industries).

Statistics Canada data does not seem to report the two-way flow of FDI between Canada and China, but it is certainly true that China has much more FDI here than Canadian firms have invested in China. This also reflects the structural reversal of China’s role in the world economy in the last 5 years. China is now one of the world’s largest sources of outgoing FDI, and they are clearly weaning themselves off dependence on incoming FDI (whether for financial or technological reasons). China’s mercantilist policies — deliberately running large ongoing balance of payments surpluses — have generated enormous resources to support their outward global expansion. Of course, when they do accept incoming FDI, they attach powerful conditions to it: including compulsory joint venture arrangements with domestic firms, and technology transfer protocols.

The consequences of the bilateral deficit

Canada’s total current account balance last year was a large $63 billion deficit (equal to over 3 percent of GDP). The China deficit accounted for almost three-quarters of that.

I find it odd that we pay so much attention in Canada to the federal government deficit (which is financed mostly with money we borrow from ourselves, in the form of bonds), and almost no public attention to the much larger deficit with the rest of the world (including China).

Based on the average shipments per worker recorded in Canada’s manufacturing sector, I estimate that the bilateral trade deficit with China is equivalent to the loss of 125,000 Canadian manufacturing jobs. So the emergence of that deficit since the turn of the century has been an important reason (though not the only reason) for the loss of manufacturing jobs in Canada in the same period. (Total manufacturing employment has declined in Canada by 500,000 positions since 2000.)

Options for Canadian trade policy with China

Given China’s importance in the global economy, we want to be engaged with China, no doubt about that. But we need a more nuanced and strategic approach than simply saying we need to promote “more trade.” And we certainly need to preserve more capacity to manage the bilateral relationship, than would be permissible under a standard NAFTA-style free trade deal.

After all, we’ve had a lot more trade with China since 2000 — and it’s been disastrous for Canada. Our total two-way trade exploded by over $70 billion between 2000 and 2015, but three-quarters of that growth was imports. In the last three years, our “trade” with China grew by $16 billion — 95 per cent of which was new imports!

Instead of blithely pursuing trade for its own sake (no matter which way it goes), our trade approach to China must involve establishing mechanisms to ensure that trade is more balanced, both quantitatively (reducing the large, job-destroying deficit) and qualitatively (ensuring that China buys more from us than just resources). This will require a much more interventionist approach to managing the two-way relationship, than is implied in a standard FTA. Instead, we need to use active policy levers to boost exports to China (especially of value-added merchandise and services), limit the size of the bilateral imbalance, and attach conditions to FDI to ensure that it is enhancing Canadian long-run capabilities in key areas.

In other words, to successfully trade with China, we had better start emulating the Chinese.

The Australian example

Australia has recently implemented a new FTA with China, negotiated by the right-wing Liberal-National Coalition government there, and coming into effect on December 20 last year. The Australia-China relationship is a bit different than Canada’s quantitatively, but quite similar qualitatively. Some FTA proponents are advocating the Australian deal as a precedent that Canada should follow.

Australia has a trade surplus with China, based solely on enormous exports of resources (especially iron ore and coal). But that foundation is crumbling, in the face of low global prices for resources and China’s industrial pivot (moving toward a less resource-intensive, consumer-driven growth path).

Another important export from Australia to China is higher education: there are hundreds of thousands of Chinese students in Australia, paying expensive, deregulated tuition fees. They are allowed to work in Australia, typically for very low wages (and thus Aussie employers like the system). That strategy, too, is time-limited: in part because China is rapidly developing its own world-class universities, and will become less enamoured of expensive foreign schooling.

In terms of imports, Australia buys the same sorts of things from China as we do: an increasingly complex and value-added slate of manufactures.

The Australia-China deal (along with parallel FTAs with Japan and Korea) were negotiated by the government in Australia just as the resource boom was collapsing. So Australia’s bilateral surplus with China (which has helped offset its big trade deficits with most other countries) is shrinking rapidly: the surplus declined by 60 per cent between 2013 and 2015 (from $A47 billion to under $A20 billion last year). Australia’s overall current account deficit is even bigger than Canada’s (approaching 5 per cent of GDP), so the erosion of this surplus with China will have implications for aggregate demand, the growth of Australia’s large foreign debt, and other macroeconomic variables.

Another problematic aspect of the Australia-China FTA is its far-reaching provisions allowing for the importation of Chinese workers to work on projects involving Chinese firms. The precedent for this provision was set in the Australia-Korea FTA a year earlier. Strong public pressure forced the Australian government to attach a labour market test to the labour mobility provisions of the China deal. But the deal will nevertheless facilitate a greater inflow of Chinese workers to Australia, adding further to the over 1 million foreign guest workers already in Australia (including students, “backpackers,” and 457 visa workers — similar to the Temporary Foreign Worker program in Canada).

In short, the Australia-China FTA is certainly no role model for how to improve Canada’s relationship with China: to the contrary, an FTA would certainly exacerbate the existing bilateral imbalance, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Jim Stanford is the Harold Innis industry professor of economics at McMaster University.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.