The idea that empowering “wealth creators” should be the goal of economic policy has been sold to the public by social democratic and conservative leaders alike. But promoting private investment through corporate tax breaks and income tax reductions for the wealthy has increased inequality, not promoted wide prosperity.

With government assistance, enormous financial wealth has been created, much of it accumulated by the top 1%.

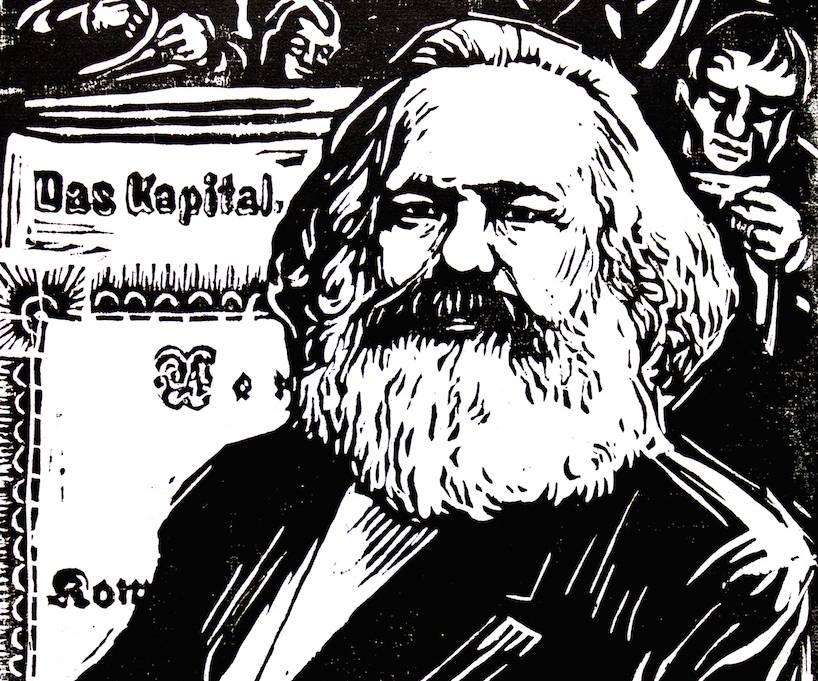

For those who have studied the ideas of Karl Marx, the economic thinker and political activist born 200 years ago on May 5, 1818 in Triers, Germany, the idea that increased wealth accumulation by the few goes hand in hand with the difficulty of earning a living wage for the many, hardly comes as a surprise.

Additional capitalist income is created when workers are paid less than they produce. Therefore the incentive to pay your own workers only as much as they need to stay alive is germane to profit seeking.

As revenue increases faster than the wage bill, the difference — profit — is pocketed by the owners (most often corporations) who employ the workers.

In the 19th century, both John Stuart Mill — the most famous English liberal — and Karl Marx — the most esteemed socialist — agreed that it was labour that produced value for owners.

It remains true today that what workers can produce is sold for more than they earn.

The source of income growth and financial accumulation is the continued exploitation of labour, and not the farsighted entrepreneur still given legitimacy by economics textbooks.

Many working people see living standards pressured by the struggle to pay back student debts or consumer loans, or meet mortgage payments, all to enrich financial capital.

In Canada and other wealthy societies, a growing “precariat” fends for itself to pay the bills. This mass of people struggles to keep body and soul together through part-time work for low wages.

Precarious work represents profits for the buyer of workers’ labour and also for giant employment firms that arrange for contract labour to be hired out by the hour.

A recent biography of Karl Marx suggests he is more relevant today than he was in his own time or even in the 20th century when his impact was so widespread.

Why? Because the appropriation of Marx by political parties, beginning with the German Social Democrats in the 19th century and continuing throughout the 20th century with the various tyrannical communist states, associated “Marxism” with the state as actor and creator of new societies, while Marx worked most of life to explain the historical, worldwide expansion of capital.

Social science research must build from a solid foundation. Rather than organize his work to answer a question, or elaborate a model or framework of analysis, or to plan for revolutionary regimes, Marx made economic history the basis for his analysis of capital accumulation.

When Volume I of Capital was published in 1867, no one would have confused it with a how-to-govern-a-state manual.

The subject of the greatest work of Karl Marx was the production and reproduction of material life in pursuit of capital accumulation.

There is much to be learned from Capital about free trade, the expansion of capital, the exploitation of former colonial lands and demeaning of Indigenous peoples, and about how to think about the world.

The ahistorical nature of much academic research, especially in economics, reduces its ability to teach people much worth knowing about their lives.

Interestingly, feminist economists have brought a deeper perspective to understanding how economies work by building on the Marxist idea of social reproduction of material life.

Rather than focus on how prices regulate supply and demand, Marxist social science offers insights into how culture, laws and institutions develop out of material existence in everyday life.

Working from Ancient Greek and Latin sources, filtered through German philosophy, Marx developed a theory of history, perhaps his most lasting legacy.

Social classes in conflict drive history through the opposing roles each played in producing and reproducing material life. Serfs tied to the land owned by aristocrats produced a feudal type of society; workers selling their days to owners produced a society organized around capital accumulation.

Anglo-American sociology, and, especially, economics, may have banished social classes from their analysis, but social classes themselves keep intruding into political life.

Unhappily those who have become “alienated” (as the young Marx put it) and angry in a society depriving them of a reasonable livelihood — while seeing others with outrageously large fortunes — can become hostile to immigrants, reject mainstream politics, and vote for a Doug Ford or Jason Kenney-led party in order to “get even.”

The rise of extreme right parties in Europe, the election of U.S. President Trump, and Brexit are what an economy failing to deliver for its citizens produces.

Marx co-wrote the Communist Manifesto (with Friedrich Engels), but it is his entire corpus of work, including journalism and essays, as well as Capital that inspires contemporary seekers of justice for working people, as they challenge the legitimacy of the capitalist class, organize to de-commodify labour and take back public space for debate, and kindle discussion of an alternative, better, lifeworld.

Duncan Cameron is president emeritus of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.