•U.S. unity restored? There was much media rhapsodizing about a post-inaugural TV set piece between three U.S. ex-presidents from opposing parties — Clinton, Bush and Obama — on a “classical” background and actually getting along! It evoked James Garner, Jack Lemmon and Dan Aykroyd in the silly film My Fellow Americans having a seriocomic adventure as three ex-prezzes.

The trouble is, there’s never been a lack of unity among U.S. political and economic elites. They’ve always got along; they agree on basics, if not details. The trick’s been dragging enough of the rest of their nation with them. Trump managed to cleave off a sizable section of “non-college educated working-class whites,” thus blowing up the superficial unity that earlier presidents relied on.

That’s the essence of his right-wing populism — an appeal to bigots and ignoramuses, plus former factory workers still shattered over losing everything to free trade. Their degradation into shock troops for a racist wannabe autocrat is the tragedy of what used to be called the American working class. Canadian poet Milton Acorn said, “I have always treated the working class as kings in exile.” Trump treated them as chumps to advance his interests.

Now there’s unity again, among the elites. But it won’t end populism. Other Trumps — not the bloated, deflated one struggling to salvage the golf clubs and hotels that few of the followers he “loves” could afford — are already planning a renewed push. What’s the point of unity if it doesn’t do anything (aside from going to the moon and other one-offs) to improve people’s lives?

That type of unity in its U.S. version at most benefits individuals, like Amanda Gorman, the precocious young poet hailed after the ceremony. The individual, like her, Obama or Kamala Harris, takes precedence over the social unit. Changing that would require programs like health care or debt relief on a broad scale, simultaneously obviating the need or expectation for another populist saviour. It’s not unthinkable. It’s readily found in other “advanced” nations. If you wanted, you could call it left populism, if it existed in the U.S.

I wonder if that was on Bernie’s mind as he sat alone in the bleachers after the big show, gazing into his mittens.

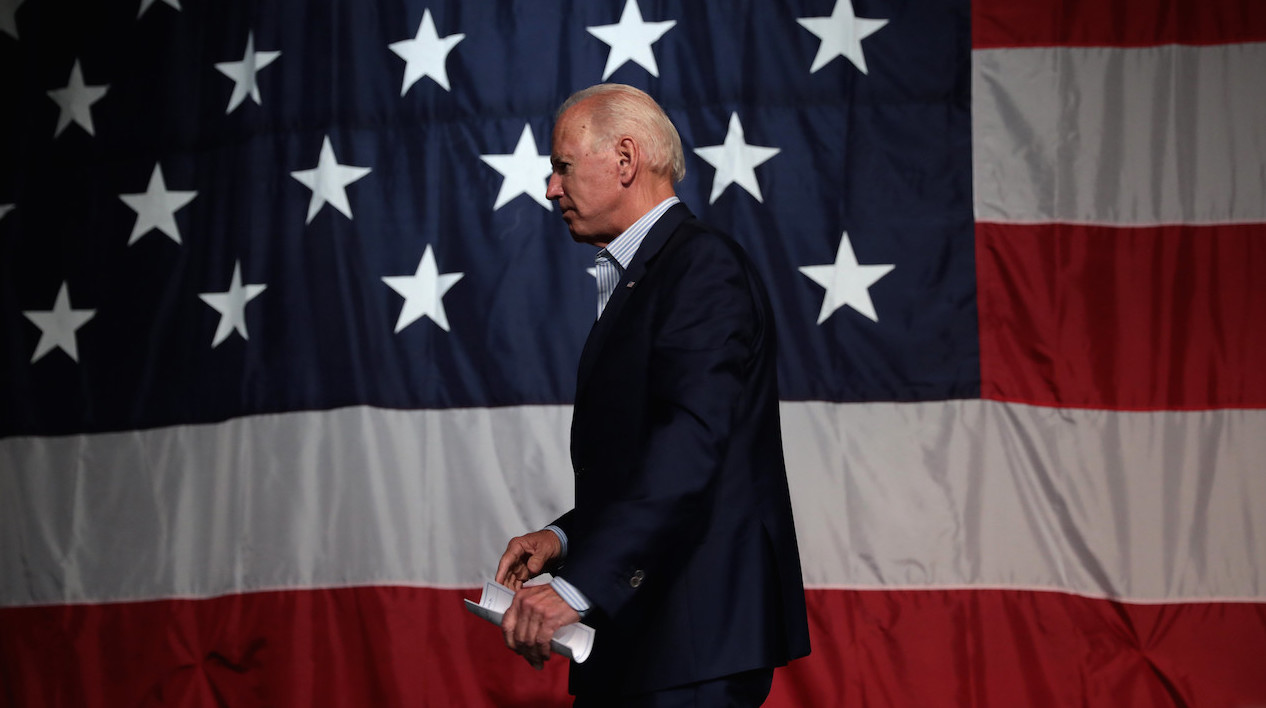

•The prodigious religiosity of the U.S. was on show at the inauguration. Those sworn in bring their own Bibles. Joe Biden goes to mass first. “Amazing Grace” seems to be the national anthem. There’s an opening prayer and closing benediction. Journalists say they never saw so much religion at the event.

The Senate race on which the future of the U.S. turned was won by a leftish Black pastor, Raphael Warnock, who leads Martin Luther King Jr.’s former Atlanta church. One of the intriguing aspects about current U.S. politics is the challenge from the once prominent progressive wing of U.S. Protestantism to the crude, “prosperity gospel,” right-wing versions that now dominate politically.

Warnock says his economics is based on Matthew 25, much as the global campaign for debt relief has been rooted in the biblical Jubilee year laws.

Overall U.S. religiosity remains traditional, even backward. Fifty-five per cent say they pray daily versus 6 per cent in the U.K. Forty per cent hold a “strictly creationist” view of human origins and others embrace modified versions of creationism. That old-time religion is good enough for them. China, on the other hand, has 64 per cent for evolution. The U.S. is more in line with Saudi Arabia, where 75 per cent are creationists.

There is indeed something quasi-religious in the current U.S. political impasse: faith vs. faith, good vs. evil, absolutes clashing, no compromise. There’s an echo of Europe’s religious wars in the American “carnage” that Trump evoked at his own inauguration, then incited at this month’s putsch. He used Twitter the way Martin Luther nailed his theses to the church door — to promote heresies against official doctrine — and got excommunicated for it.

Canadian media scholar Harold Innis felt Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press circa 1440 (the Bible was the first book he printed) shut people up in their private reading worlds. This reduced the tolerance more typical to the collectively shared experiences of the preceding oral tradition, leading to fanaticism and over a century of gory religious war. Sounds like Twitter to me.

Rick Salutin writes about current affairs and politics. This column was first published in the Toronto Star.

Image credit: Gage Skidmore/Flickr