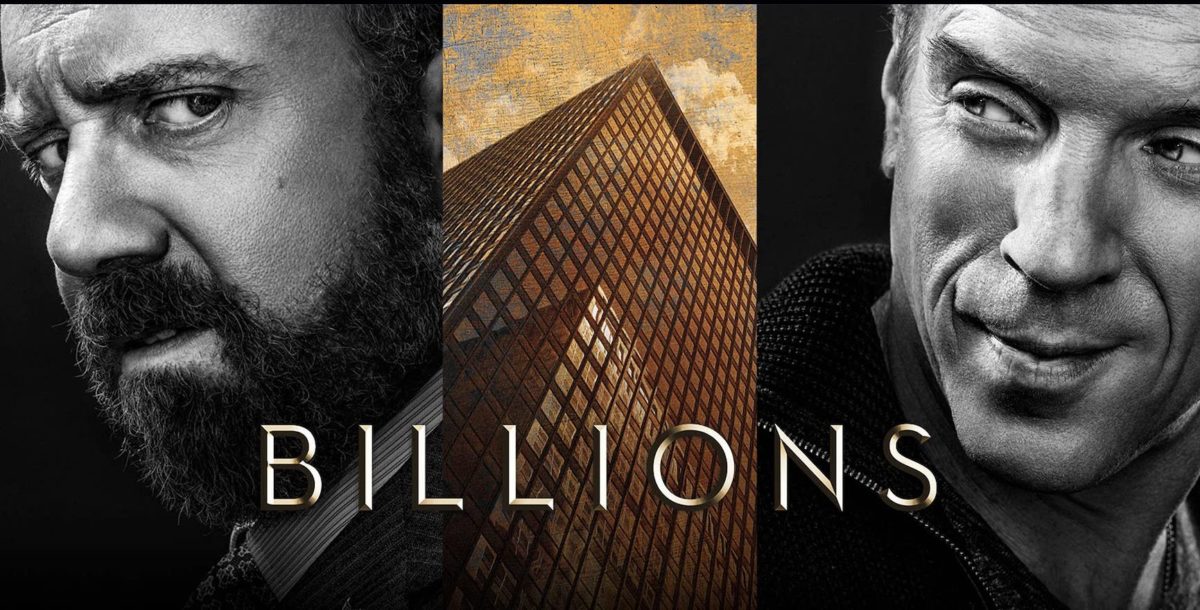

I watched the finale of Billions on Sunday, after five seasons, when voracious Bobby Axelrod, of Axe Capital, was finally (spoilers in two, one…) taken down by his mirror image, the crusading DA-type Chuck Rhoades. The show will limp into a new era next year when Chuck pursues Bobby’s successor, who ended the episode in Bobby’s office, sitting in his very own, gasp, ergonomic chair.

It’s been turgid TV, distinguished by self-consciously Shakespearean diction and cadence: characters spoke in full sentences that others waited for them to finish. I never knew why I stuck with it, but then I watched The Rookie. Only at the end did I realize it nails a dominant feature of economies today: they’re about little except money, referencing itself in endless circles. They’ve managed to disappear the actual stuff economies produce: goods, services, health, fun. And our society approves this haze, as proven by Billions. That’s the show’s achievement: to wholly conceal real economies at last.

This tendency was noted by leftists like Lenin a century ago. But they stigmatized it and gave it a name: “financialization.” You could shudder and realize something was going rotten. In Billions it’s normalized; there’s no complementary reality. The office at Axe Cap is sterile and white. The only real-life stuff there implies oral fixation: vintage pizza (!), booze, cigars. They’ve achieved the monetization of money; it’s only ever about more money.

I’m not saying I miss the factory floor or the workers. But I do miss the tension and criticism you once got. Financialization now seems like a state of nature, though you still find real anger in work by the (sadly) late David Graeber or Michael Hudson. They focus on debt as the sign of terminal financialization.

It can be exhilarating to realize the disappearing trick that’s been pulled off. Marx admired it: human social reality is suddenly — presto — gone. Money appears to speak and act, it has needs; humans are just objects it uses.

It you get that, and escape the illusion of the premise, Billions can help in understanding things like recent changes in China’s economic policies. I speak not of the Uyghur genocide or the crushing of Hong Kong. I mean the unexpected attack on billionaires; a ban on private tutors for the privileged; a focus on narrowing inequality. What happened to China’s Wild West capitalism and “it is glorious to get rich”? Did they snap and revert to communism?

Hudson is especially good on this. His hatred of debt is rooted in studies of the ancient Mideast (Sumer, Babylon, Israel). As the power of kings and nobles grew, debt became crushing. The few lived off rents while productivity in agriculture waned. People were impoverished or enslaved, stagnation followed, and some fled or rebelled. The remedy back then was periodic debt forgiveness, like the Bible’s Jubilee year. The comparable catastrophe today is inequality and symbolic enslavement through unpayable debt. The superrich, like those in Billions, don’t produce. Mostly, they live parasitically off “rents” from loans, insurance and real estate. This tends inevitably toward effects as grotesque as feudalism.

Hudson sees China’s economic rejigging as an attempt to escape these logical consequences of living inside the financialized global economy. It’s trying to counter the wealth gap by narrowing the advantages of the rich and limiting the effects of debt by, for instance, calming the housing market, so that it becomes, well, housing, versus a source of bottomless debt. In China, the state can do all this by fiat.

You can see these policies as a crazy reversion to communism, or you can see them reflecting China’s traditional nationalism. It too wants to be great again, as it was until the centuries of humiliation by western imperialism. I think the latter fits better, though there’s room for the former. One Chinese commentator, quoted in the Financial Times, says that Trump encouraging people to deny the election and invade Congress was more like Mao’s Cultural Revolution than any policy promoted in China today.

It’d be delightful to see someone hit an anti-financialization note in a future Billions episode. Something like it did occasionally happen in Mad Men, though that’s another kettle of capitalism.

Whatever. I expect I’ll still be watching when they swing by again.