When the first planeload of former Afghan interpreters disembarked at Toronto’s airport the evening of August 4, they were greeted by a number of Trudeau cabinet ministers. Conspicuously absent from the welcome party was Minister of War — sorry, “Defence” — Harjit Sajjan.

Sajjan’s absence was telling for a government so focused on photo-ops celebrating its alleged benefaction. During the following weeks, as thousands more have desperately sought refugee flights to Canada, there are quiet whispers that could point to why Sajjan was, and remains, far away from the cameras with each new arrival. Those whispers could be crystallized in two words. “Everybody knew.”

What does everyone know? Afghan refugees in Canada are not likely to speak on record at this time, but a number have shared with me what is common knowledge both in their diasporic communities and back home. In essence, among the individuals Canada is bringing here, there will be interpreters, fixers, drivers, liaisons, and others who were “in the room” or knew what was going on when the Canadian Forces were knowingly transferring farmers, shopkeepers, teachers, and countless other Afghan civilians into the hands of torturers.

Of course, Canada does have a responsibility to evacuate as many of its former Afghan contractors and their families as possible. These are individuals who were placed in an impossible situation: to feed their families, they took on relatively well-paying, high-risk gigs facilitating the work of a brutal NATO occupation force which killed, tortured, and injured hundreds of thousands of people. While many Canadian veterans have led a valiant struggle for well over a decade to help get these individuals and their families out, that campaign does not appear to have received one iota of support from the generals, other military brass and politicians who have a vested interest in keeping out potential witnesses to Canadian war crimes in Afghanistan.

It has been heartbreaking watching the crush at the Kabul airport. But few seem to recall that this last-minute dash to take control of Afghanistan could have been prevented if there had been a serious commitment to the lives of those in Afghanistan who enabled the Canadian military occupation.

Canada never cared

In 2009, then-immigration minister Jason Kenney announced a program to accept interpreters on a fast-track, yet two years later, the Canadian Press reported that over two-thirds of Afghans who worked with the Canadian military in Kandahar had been turned away.

“Working as an interpreter for NATO forces in southern Afghanistan was akin to having a Taliban bull’s-eye on your back,” the report noted. “Stories of night letters, threatening phone calls, abductions and even hangings were part of the job.”

Then as now, the rules of the immigration program were hopelessly labyrinthine. For example, one could only qualify to come here if they served a consecutive 12 months, but if that period started before the arbitrary marker of 2007, they were deemed ineligible.

The racist contempt the federal government has shown to its former Afghan contractors (who notably were forced to use segregated washrooms in a scene out of 1940s Alabama) is similar to the disrespect Ottawa regularly shows the veterans who have been lobbying so long on their behalf. These soldiers know first-hand the dangers faced by those left behind. It’s not a new risk at all, but rather one that has always existed, because the Taliban and other forces opposed to the occupation never went away.

When the Canadian transfer of detainees to torture was major news 15 years ago, former translator Ahmadshah Malgarai, a cultural and language advisor with secret clearance, bravely told a House committee in April, 2010:

“There was no one in the Canadian military with a uniform who was involved in any way, at any level, with the detainee transfers who did not know what was going on and what the NDS [Afghanistan’s tortured-tainted National Directorate of Security] does to their detainees.”

By extension, that would have to include the other translators, fixers, and liaisons. Critically, it would also include Minister Sajjan, his predecessors, and the military decision makers in Ottawa. In fact, it was this group of military brass and political operatives who intended that certain Afghans be tortured in order to gather “intelligence,” as University of Ottawa professor and lawyer Amir Attaran (who played a front-line role in exposing such crimes in the 2000s) pointed out in 2010. In the battle to secure unredacted documents related to the transfer of detainees to torture, Attaran told CBC:

“If these documents were released [in full], what they will show is that Canada partnered deliberately with the torturers in Afghanistan for the interrogation of detainees. There would be a question of rendition and a question of war crimes on the part of certain Canadian officials. That’s what’s in these documents, and that’s why the government is covering up as hard as it can.”

Canada in factual cleansing mode

As Canada closes its embassy in Kabul, there is no doubt a great deal of paper shredding going on. At home, Ottawa is in full factual cleansing mode, using the dramatic evacuations as a starting point for completely rewriting the deadly and illegal Canadian occupation as a feel-good, well-intentioned, noble narrative about feminism and peaceful development that papers over the geopolitical violence that undergirded the original decision to invade.

Indeed, the mission itself was part of a larger, brutal purpose, where the Afghan people were mere “collateral damage” in big power games, and on-the-ground soldiers were equally expendable in the eyes of generals and political leaders. It is those on-the-ground soldiers, and not the generals, who have had the dignity and honour to be paying out of pocket in an effort to speed the evacuations of their former contractors. Notably, such veterans, who have spent years advocating for the contractors’ transfer out of Afghanistan, have complained of being locked out of the process, despite having critical information needed to help identify and protect those most at risk.

But persistent, questioning voices remain. At the end of 2017, law professor and former MP Craig Scott submitted a war crimes brief to the International Criminal Court (ICC), in which there is ample documentation that Canadian political and military officials “may have aided, abetted or otherwise assisted the commission of war crimes or crimes against humanity.”

Scott argued an ICC inquiry would open up space for whistleblowers in the Canadian government, noting:

“I am quite confident there are multiple persons across various departments in the Canadian federal civil service who know much but who are wary of coming forward until there is a credible investigative process that stands a chance of not being stymied in the way of every other process in Canada regarding detainees to date — and thus would be more likely to come forward to investigators within an ICC process they perceive as serious.”

Scott’s meticulous brief documents “off the books” detainee transfers as well as a perfidious pattern of deceit at the highest levels of the Canadian military. Notably, Scott points out that:

“a lack of concern for the well-being of transferees need not have been — and likely usually was not — shared by the ground-level soldiers and military police who carried out the actual handovers. There is good reason to believe that many of those under orders from superiors to transfer did worry for the fate of transferees given rumours they had heard about treatment of prisoners in custody…even as they did not generally have access to the firm evidence that would prove such rumours (as would key command-level officials) and even as they may well have assumed that Canada had set up effective monitoring so that at least Canadian transferees were less likely to be abused.”

Scott confirms the comments of Amir Attaran from 2010, pointing out that “there are reasonable grounds to suspect that certain Canadian officials ran a system of sending people to the real risk of torture despite knowing (or having the legally requisite basis to know) of the real risk of torture.”

Someone was in the room

In 2007, The Globe and Mail famously reported on the fate of many detainees, such as a 33-year-old farmer whose teeth were knocked out by Afghan interrogators. In a legal brief prepared by Amnesty International and the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, they noted that this farmer “claimed that Canadians visited him between beatings, heard his screams, and urged him to provide his Afghan captors with intelligence.” A Canadian-contracted interpreter must have been on-site to translate for the now bloodied detainee, and could now be called as a war crimes inquiry witness.

Meanwhile, in a move that may have had many quaking in their boots, in March 2020, the ICC unanimously authorized “the Prosecutor to commence an investigation into alleged crimes under the jurisdiction of the Court in relation to the situation in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.”

While there has yet to be further news on this front, the fact that the door remains open provides hope for some measure of the accountability so many Canadian officials hope to avoid.

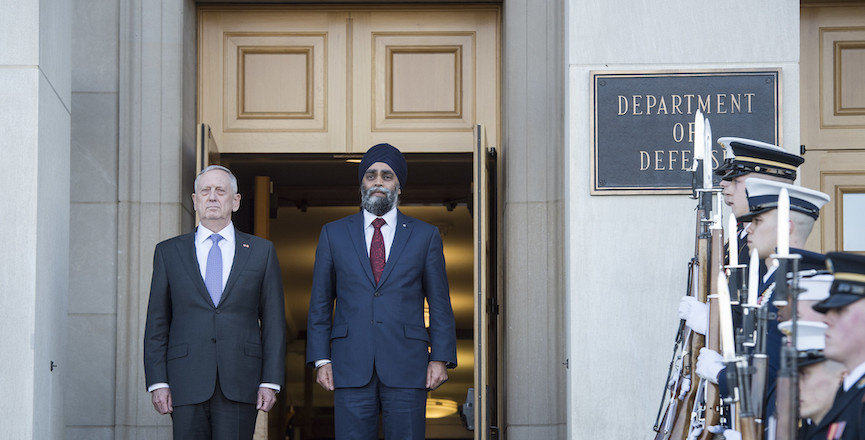

Among those with the most to lose here would be Sajjan, whose 2015 appointment as war minister was at the time widely celebrated. The National Observer enthused: “You don’t know how badass Trudeau’s Defence Minister really is” and hailed him as “the best single Canadian intelligence asset in [the Afghan war] theater.”

But Sajjan’s appointment by Trudeau may have opened a Pandora’s box that former PM Stephen Harper thought was sealed when he prorogued Parliament in 2009 to avoid questions about Canadian complicity in the torture of Afghan detainees. Indeed, Sajjan’s overseas tours as a key Canadian asset and liaison with torture-tainted Afghan authorities dovetailed with an era when significant human rights concerns had been quietly raised by Canada’s foreign affairs representatives about military, intelligence and police force involvement in arbitrary arrests, kidnapping, extortion, torture and extrajudicial killing of suspects.

In 2006, as Harper’s Conservatives took over a war begun by the Liberals, Graeme Smith’s remarkable Globe and Mail reporting — along with courageous statements of Canadian whistleblower Richard Colvin, a diplomat in Afghanistan — brought to light terms like “war crimes” to describe Canadian transfers of detainees to the torture-stained Afghan NDS. The Harper government faced potential contempt of Parliament proceedings over its refusal to release thousands of documents related to the scandal.

Torture as standard operating procedure

Colvin, who’d served 17 months in Afghanistan, testified in 2008 that Afghans transferred from Canadian Forces to the NDS commonly faced:

“beating, whipping with power cables, and the use of electricity. Also common was sleep deprivation, use of temperature extremes, use of knives and open flames, and sexual abuse — that is, rape. Torture might be limited to the first days or it could go on for months. According to our information, the likelihood is that all the Afghans we handed over were tortured. For interrogators in Kandahar, it was standard operating procedure.”

Colvin noted many detainees had nothing to do with the Taliban:

“many were just local people: farmers, truck drivers, tailors, peasants, random human beings in the wrong place at the wrong time, young men in their fields and villages who were completely innocent but were nevertheless rounded up. In other words, we detained and handed over for severe torture a lot of innocent people.”

While ongoing inquiries were effectively shut down with the 2011 election of a Harper majority, the issue arose again in 2015 a week before the Trudeau team officially took charge in Ottawa. But amidst what seemed the national lifting of a grim mood following a nasty election (in which Harper’s team had questioned the loyalty of niqab-wearing Muslims and proposed a Barbaric Cultural Practices Hotline), little attention was paid to the Military Police Complaints Commission announcement that it would investigate a new case in which Canadian soldiers allegedly abused and “terrorized” Afghan detainees at their Kandahar base. That same week, researcher Omar Sabry and the Rideau Institute released a new report calling for a “transparent and impartial judicial Commission of Inquiry into the actions of Canadian officials, including Ministers of the Crown, relating to Afghan detainees.”

But who would decide whether to proceed with such an inquiry? It seemed that Sajjan, Canada’s hip new war minister, might have to recuse himself from any role in considering the issue, given he could be compelled to answer some very difficult questions. As a high-level intelligence officer who appears to have taken an active role in combat operations, it seemed implausible that Sajjan was not familiar with the torture rampant throughout the Afghan detention system. Indeed, in 2006, Sajjan became the Canadian “intelligence liaison” to Kandahar governor Asadullah Khalid.

According to Colvin’s Parliamentary testimony, Khalid:

“was known to us very early on, in May and June 2006, as an unusually bad actor on human rights issues. He was known to have had a dungeon in Ghazni, his previous province, where he used to detain people for money, and some of them disappeared. He was known to be running a narcotics operation. He had a criminal gang. He had people killed who got in his way. And then in Kandahar we found out that he had indeed set up a similar dungeon under his guest house. He acknowledged this. When asked, he had sort of justifications for it, but he was known to personally torture people in that dungeon.”

(Khalid went on to become Afghanistan’s national intelligence chief).

Torturing a 90-year-old man

Sajjan is also credited with the intelligence gathered for operations that led to the “kill or capture” of some 1,500 alleged Taliban members, a military claim that must be measured against the commonplace reference to any detainees as potential Taliban, as opposed to the broader categories of detainees translator Malgarai referenced in his testimony:

“They went from 10 years old to 90 years old. With all due respect, I would ask retired General Hillier to tell me and explain to me how a 90-year-old man…He was a 90-year-old man. He couldn’t even walk without help. His hands were tied. His foot was shackled. He was blindfolded. Sometimes, when he couldn’t walk fast enough, they pushed him. He fell many times, and he had injuries on his body. Could he please explain to me how this 90-year-old man, who couldn’t even walk, who needed help when you tried to pick him up, could be a fighter?”

As Ottawa celebrated the new Trudeau government, serious questions were raised but unanswered. Would Sajjan discuss whether he undertook precautionary measures to ensure that he was not passing on to his superiors information gleaned from torture (especially given his liaison role with Governor Khalid and the widespread and well-known use of torture by the NDS in Afghanistan by the time of Major Sajjan’s first tour of duty in 2006)? Alternatively, was such information caveated to the effect that its source may have been the fruits of torture?

Equally compelling, in the small, circular world of intelligence operations, was information gleaned from NDS torture of detainees used in the Canadian round-up of individuals who, upon detention, were transferred to the hands of NDS torturers. Ultimately, given his likely awareness of torture in Afghanistan, did Sajjan refuse to take part in any operational activity that may have led to the transfer of detainees to torture?

When the Harper government closed the case in 2011, Liberal MP Stéphane Dion told the CBC “the likelihood is very high” that Afghan detainees were abused while in the custody, adding, “I don’t think Canadians will accept that it’s over.”

But Dion was silent when, in June 2016, Sajjan rejected public calls for an inquiry which, by this time, had received the support of everyone from former Conservative Prime Minister Joe Clark and leading Canadian law faculty to former NDP leader Ed Broadbent and Amnesty International.

Ever since the 2015 election, Sajjan has seemed to run away from any association with Afghanistan. In 2017, he was accused of falsely downplaying his role in the war, as Ethics Commissioner Mary Dawson sought to determine why he would not consent to an inquiry. In a response to Dawson, Sajjan beggared belief by claiming, according to Dawson’s notes, that “[a]t no time was he involved in the transfer of Afghan detainees, nor did he have any knowledge relating to the matter.” He may have been the only one in Afghanistan not to know.

It was a remarkable walk back from the public record, in which his commanding office, Brigadier General David Fraser, described him as someone who “singlehandedly changed the face of intelligence gathering and analysis in Afghanistan.”

Ultimately, Dawson meekly concluded, based only on interviewing Sajjan and speaking with no one else, that there were no grounds for an investigation.

Sajjan’s dismissive dispatch of the issue shocked many in the legal community who held out hope that campaign commitments to transparency and accountability would survive beyond election day. Four years and two elections later, Sajjan is on the campaign trail once again, trying to burnish his image as the wise saviour of a people in whose torture he may well be complicit. As we welcome Afghan refugees and work to save as many as possible from the likely retaliation they face if left in Afghanistan, the failure of Ottawa to take care of its former contractors for well over a decade may well warrant an inquiry in itself.

Meanwhile, the manner in which Canadian complicity in Afghan torture has corroded basic democratic principles and put thousands of lives at risk continues to reverberate here and around the globe. As those most responsible for these crimes continue to run away from them, they rely on exercising the levers of governmental secrecy to protect their paycheques, pensions, book deals, and the other perks that come with the sick celebration of militarism that was a mainstay of the Afghan occupation.

Matthew Behrens is a freelance writer and social justice advocate who co-ordinates the Homes not Bombs non-violent direct action network. He has worked closely with the targets of Canadian and U.S. “national security” profiling for many years.