While I posted about the 1974 Anicinabe Park Occupation in Kenora elsewhere I feel it deserves its own thread.

In 1974 I had just read Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee, when I set out to drive a motorcycle from Ottawa to Vancouver. In Thunder Bay I met two Americans heading for Alaska so we travelled together for a week.

When we reached Kenora we camped outside of town and went to a bar in the centre of Kenora at night. As soon as we entered it was obvious that there was an unofficial line splitting the bar into the white and native sides. We sat near the border between the two groups. With our motorcyle leathers on, it was obvious from the strong glares we were getting that we were considered "biker's" by the redneck whites. Perhaps because of that, one of the First Nations came over and started talking to us. Over time, quite a few others joined us.

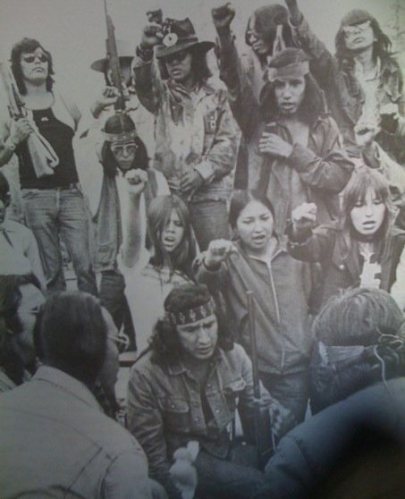

They told us that some of the young First Nations had occupied Anicinabe Park on the outskirts of town and that they had help from the American Indian Movement (AIM). Their were demands were better living conditions, education and access to land. They told us that the park land had been stolen from them 25 years before without the town even bothering to go through a legal process. They also warned us that the RCMP had road blocks up to prevent other First Nations from joining them. Sure enough, when we headed back to our camp we were stopped by the RCMP. They asked if we were gun-running "to the Indians". Perhaps they thought that was the only reason we would be talking to First Nations in a bar under these circumstances.

The next day we crossed the border from northern Ontario into Manitoba. We stopped at a gas station and asked if they minded if we could change the oil in our bikes at the side of the station. "No problem and we'll even give you a pan to change your oil."

One of the two attendants stuck around as we changed our oil talking to us in a friendly manner until he brought up " the local Native problem". He said the gas station had a small convenience store attached to it and some First Nations people came to the store to buy vanilla extract for the alcohol in it when they couldn't get it any other way. So two weeks before they had decided to stop selling it to them. His co-worker came over to back up the story. So we asked what happened. They said they were waiting with a rifle sticking out the door and pistol sticking out the window whenever a car or truck full of "Indians" drove up. We left as quickly as possible.

On my trip back from Vancouver to Ottawa a couple of months later, I stopped in Kenora again where I met a man who was half Native and half Black, according to him the only one in Kenora. When we tried to go to a bar together, the bartenders in several bars said although I could come in, he was repeatedly not allowed to enter without being offered any explanation, so I left with him.