Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

As one of many Alberta university history instructors busy marking students’ final research essays this term, I’m instinctively aware how important it is to critically analyze our past in order to come to a fuller understanding of how we got to where we are now.

It was with this in mind that I came across Canadian Taxpayers’ Federation Alberta chief Paige MacPherson’s open letter to the NDP government published in the Edmonton Journal.

In the piece, Macpherson compares Alberta’s current situation with the Alberta that faced the Great Depression of the 1930s. Her basic point, as far as I can discern, is that the decisions made by the Alberta Social Credit government led by William “Bible Bill” Aberhart in 1935 to combat the Depression, including “taking hold of the financial system” and “dishing out monthly payments to Albertans” did nothing to reduce Alberta’s debt, which, according to MacPherson, was Alberta’s main problem going into the Depression.

Never mind the large-scale and fundamental problems with the workings of international capitalism.

The main result of the government’s actions, according to MacPherson, was that Albertans responded by trying to cash in their Alberta Savings Certificates. Albertans, and other investors, had simply lost confidence in the government. In the 1930s, as now, she argues, Alberta’s debt was too high because its spending was out of control and the government “simply couldn’t pay the bills” as a result.

I won’t take issue here with MacPherson’s misleading and disingenuous contention that Alberta’s current debt stands at $17 billion. That I shall leave to David Climenhaga’s latest post.

What I will take issue with is MacPherson’s misleading and disingenuous use of Alberta’s past to take cheap shots in the present.

For MacPherson, Alberta was “drawn into” the Great Depression of the 1930s for three reasons: first, Alberta’s economy was highly reliant on export markets for its main staple export, wheat. Second, the price of wheat worldwide was low. And finally, much of Alberta’s export market was closed because other nations (read: the U.S.) had imposed high tariff barriers in a misguided effort to protect their own markets.

What lessons has Alberta failed to learn from this misreading of the past? MacPherson trots out the usual suspects that supposedly unfailingly lead to severe economic problems: big government, high taxes, over regulation, skyrocketing public spending, and bloated salaries in the public sector. Of course.

The problems with this analysis begin almost immediately. Alberta wasn’t “drawn in” to the Depression. It was instead a victim, along with every other province in Canada, of the culmination of basic contradictions in industrial capitalism that were decades in the making.

MacPherson also fails to notice that Albertans voted for a Social Credit government in 1935 largely because the governing United Farmers of Alberta were, like governments throughout the western industrialized world, unable to solve the economic problems of the Depression. It’s worth noting that no fewer than seven of Canada’s then nine provinces changed their governments around the same time Alberta did — and Canadians as a whole voted out Richard Bedford Bennett’s Conservatives in the 1935 general election as well. Alberta’s story, in other words, was far from unique.

It is true that Alberta’s economy in the 1930s was highly reliant on export markets. It still is today. What is not true is that Alberta was facing high tariff barriers in 1935. The American Hawley-Smoot tariff, enacted in the U.S. in 1930 to protect that nation’s domestic market, was largely dismantled by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt after his election in 1932. Roosevelt and his administration understood that hampering trade and reducing spending were exactly the wrong policy moves in hard economic times. More to the point, these policy directions (ones that presumably MacPherson would support today) actually exacerbated the Depression by hampering its recovery.

MacPherson also cites the low price of wheat as a problem at mid-decade. Baloney. If she bothered to examine the evidence, she might have noticed that by 1936 the price of wheat had actually recovered to near its 1929 level, just before its precipitous drop following Black Tuesday in October of that year. From its high of $1.24 per bushel in 1929, wheat fell to a low of 59 cents in 1931. Thereafter, it enjoyed a steady increase to $1.22 per bushel in 1936. The price rose even higher the following year to more than $1.31, before falling once more. But by that time, the Canadian West was largely on its way to recovery.

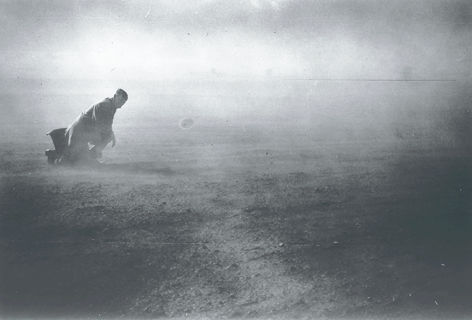

The price of wheat wasn’t the problem. Instead part of the problem was the dustbowl conditions in the southern part of the prairies that made it almost impossible to produce any wheat at all. Another part of the problem was governments’ continued tight-money policies and refusal to engage in large-scale investment in the economy.

Nor was government spending the problem. Alberta’s government in the 1930s, like governments nationwide, was small and largely non-interventionist in the economy. The real problem was that Alberta simply didn’t have a government sufficiently complex and interventionist to face the economic disaster head on, and at the very least, to mitigate its sharp effects on Albertans.

It is true that the Alberta government, again, like provincial governments across the nation, did have debt at the outset of the Depression. But that wasn’t because Alberta had been spending “recklessly” as MacPherson imagines. Instead, it was because it didn’t have any revenue-generating means at its disposal, save direct taxes. And the UFA government was loathe to raise them because, well, sitting governments generally are loathe to raising taxes.

It’s also true that Social Credit’s victory at the polls in 1935 spooked investors. And so it should have. Aberhart’s reading of social credit theory, however distorted from its original form as conceived by its author, British engineer Major CH Douglas, was spooky, and more than a little kooky (so was Douglas’s original, for the record). But none of that mattered, since most of what Aberhart wanted to do, including printing money and, in MacPherson’s words, “taking hold of the financial system,” was outside of Alberta’s constitutional competence anyway.

On this last point it’s worth noting too that the Edmonton Journal well knew this, and derided Aberhart’s plans unceasingly on its pages. Aberhart responded in 1937 by introducing his government’s Accurate News and Information Act, which would force the media to print a government rebuttal alongside anything critical of social credit. The act would not pass constitutional muster, and was struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1938 before being called into force. The Pulitzer Prize committee subsequently awarded the Journal with a bronze plaque for its role in fighting the legislation. Alas, the Post Media-owned Journal looks very different today.

Perhaps most glaringly, MacPherson’s comparison of Alberta today and the Alberta that weathered the Great Depression misses the fact that the province’s most vulnerable in the twenty-first century can at the very least look to a modest social welfare infrastructure for help, though even this has been vastly eroded since the 1990s. Alberta’s most vulnerable in the 1930s could find little more than the most meagre of government relief.

In the end, MacPherson’s position — that small government is good government; that markets correct themselves based on the simple laws of supply and demand; and that taxes ought to remain low — basically describes most governments’ position throughout the western industrialized world at the outset of the Great Depression.

If there’s any lesson to be learned from the 1930s, it’s that this position has historically not worked out very well.

Erik Strikwerda is an Assistant Professor of History at Athabasca University.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: canadianencyclopedia.ca