The “gig economy” shows the extreme side of individualist culture — each worker independent, supposedly self-sufficient, and in competition with all the others. Economically, the pendulum has swung to the other extreme from the conformity of the 1950s and early ‘60s.

I grew up in the age of ticky-tacky cookie-cutter suburban homes, Corporation Man breadwinners — employed at one firm for life — and Feminine Mystique homemakers. Everyone wanted to succeed, and the way to succeed was to “fit in” — that is, to conform. Of course, some of us never could.

Conformity offered comfort and security for those who succeeded, especially for returning soldiers. Social planners focussed on the farm boy who earned his BA and middle management job on a GI Bill scholarship, his reward for surviving the killing fields of World War II.

His home was his pride and joy, perpetually stocked with all the latest appliances, thanks to his educated and dedicated homemaking wife, who handled the machines and did all the childcare, food preparation, and other daily household work. Utopia meant a chicken in every pot, and a new car in every garage.

At the dawn of industrialization, suffragists had argued for communal laundries and kitchens as well as shared childcare, but in vain. Instead, in the 1950s, social planners upheld the nuclear family structure: the breadwinner husband and financially dependent homemaker wife.

Giant corporations swelled on the revenue from selling every individual household its own HVAC, fridge, stove, washer, dryer, dishwasher, and freezer, all administered by the housewife, whose main role in the selection process was choosing the appliances’ colour.

Corporations proclaimed their own importance with phrases like, “What’s good for General Motors is good for America.” And yet among the public, a certain discontent gathered and grew. Even well-adjusted children found the comfort of suburban conformity became stultifying and often terrifying when they became adolescents and they tried on different personalities.

Playboy Magazine arrived in 1953, singing a seductive philandering song to husbands who suddenly felt like married life was another version of the army. Women, housebound, and constantly at any family member’s beck and call, suffered mysterious maladies and had weeping spells. Most American grown-ups drank a lot. Suddenly, conformity sucked.

So iconoclastic individualism became glamourous. Hollywood discovered the bad boy, the misfit, the rebel without a cause personified by James Dean on his motorcycle, or Marlon Brando in his ripped undershirt. By the 1970s, Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson replaced them — fighters, not lovers, and none too debonair.

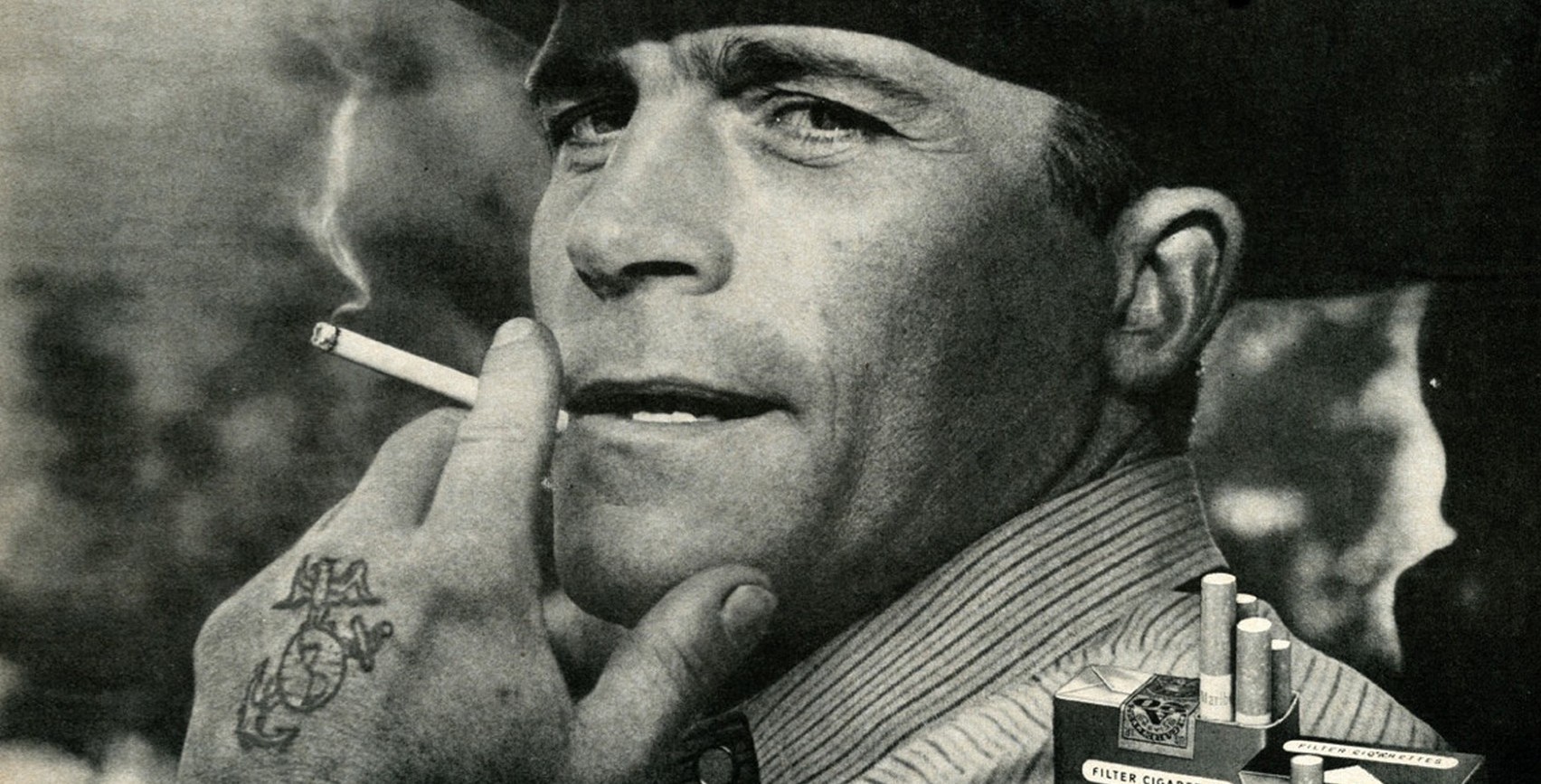

I must confess that my Dad, Hal Kome, was the advertising creative director who told the art director to put a tattoo on the hand of the Marlboro man. Dad was well versed in Freudianism. He added the tattoo to signify rugged individuality. Marlboro cigarette sales soared, and the Marlboro man became iconic.

But the competitive, individualistic model was always flawed. Not only did individuals burn out, but structures teetered and collapsed from the inherent instability of people competing instead of co-operating. Yet a certain macho streak persevered, crying, “Live free or die!” Some far-right folks in the States declared themselves “sovereign citizens,” not under the authority of any government’s laws.

In theory, sociologists say, every society can be placed on a spectrum with “collective living” at one end, and “individualism” at the other. Collectivist societies (the majority of both developed and developing countries) emphasize safety, social welfare, and programs like universal health care, but to different degrees. For example, in Japan, police officers regularly visit people’s homes so they know who is living where — a practice Canadians might find invasive.

Individualistic countries emphasize competition as the path to achieving excellence, in the “free” market. Thus in 1996, a sociology journal article pointed out that, “Individualization is considered one of the processes associated with what is called modernization.”

Which is not to say that individualization is necessarily helpful or beneficial to individuals or society. Corporations and governments decide where the jobs go. People leave their families in order to follow their jobs or their dreams.

The U.S. developed an emphasis on personal responsibility that is the flip side of the West’s goal of personal freedom — a definition of “freedom” that has excluded state initiatives such as universal health care but permitted corporate welfare. As I learned while helping to compile Peace: A Dream Unfolding (1986, Sierra Club Books), after WWII, East and West divided up the virtues. The East chose peace as their primary goal; the West chose freedom, as epitomized by a lone man on a motorcycle.

Such “freedom” was available only to a few, though. Social research turned up many excluded groups, from women, to persons with disabilities, to elderly people, to persons of colour. They were neither “free from” social constraints nor “free to” choose their own destinies.

Also, psychologists discovered that total independence often brings total loneliness, and loneliness kills people. The U.S. is the most individualistic country in the world and there, death rates have been rising for white people without college degrees. Single men and family women are especially vulnerable. Many men believed what Playboy taught, and ended up single. Actually, marriage is highly beneficial for married men, who live longer and report better health than single men.

Now the pendulum is swinging back towards collective action again, and everyone is talking about “belonging.” Attachment theory has migrated to social theory, and synthesized a much friendlier analysis of human society. No longer is the lone hero the ideal. For example:

“Research has established links between social networks and health outcomes,” says a 2009 Statistics Canada. “Social isolation tends to be detrimental to health, while social engagement and attachment are associated with positive health outcomes [as in building strong community ties]…This type of indicator supports an ‘upstream’ approach to preventing illness and promoting health…”

“Belonging” was the theme of Community Foundations, 2017 AGM, where 191 community foundations of Canada defined the term to include “affordable housing, employment opportunities and public safety” as the three top factors people want in order to feel they “belong” in a place.

The social emphasis is swinging back to recognizing how much we are all alike, how much we all have in common — an approach that runs counter to politics, which still emphasizes our differences. However, unlike conformist times, now the emphasis is on including formerly excluded groups.

The national Vital Signs report notes that “Security is essential for belonging too. Crime is on the decline in Canada and most people feel safe where they live. However, systemic racism and a lack of public services that are culturally safe still leave many without a sense of security.

“More than one in five Canadians reported being a victim of discrimination in the last five years. Meanwhile visible minorities and Indigenous Peoples both have less faith in public services such as police to protect them.”

One way to counter the gig economy is by building resilient communities with resources to share. Union organizing is crucial too, of course. Alberta’s first step towards the $15 per hour minimum wage on January 1 should show the wisdom of putting money directly in workers’ hands — in the long run.

Trends like co-housing and house-sharing show people are seeking community again, although high housing prices and climate change concerns are also factors. Car-sharing services offer access without ownership. Toronto’s two “Sharing Depots” allow access to tools and appliances on a library basis. Some 10,000 people across the country are employed in worker-owned co-ops.

Diversity is the watchword now, not conformity. Health researchers warn that the ideal of the rugged individual shortens a person’s life expectancy. Self-actualization starts with a secure and stable community base. We live in smaller spaces yet we still make our homes our own. And as for appliances? The suffragists were right. Daily chores are more fun (well, bearable) if you do them together.

Photo: Keijo Knutas/Flickr

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.