Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

One of the most controversial parts of trade and investment agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is the special status they give to foreign investors.

Foreign investor lawsuits under these agreements have exploded, growing from a few cases in the late 1990s to more than 600 worldwide today.

This explosion has happened partly because the lawsuits are extremely powerful and lucrative for companies and their lawyers, compared to other kinds of lawsuits against countries. They are so powerful, I would call them super-sized.

Thus, under the TPP, U.S., Japanese, Malaysian, and other foreign companies would get a new power to sidestep Canada’s legal system by bringing a TPP lawsuit against Canada.

Or, they could go to the courts in Canada to attempt to strike down a decision, while using the TPP to seek public compensation not otherwise available in Canadian law.

By the same token, the lawyers sitting as arbitrators under the TPP would have immense power to condemn Canada by ordering compensation for foreign investors.

The arbitrators’ awards of compensation do not have a monetary ceiling. They are available not only for the amounts actually invested in an economy but also for lost future profits. They are enforceable against a losing sovereign’s commercial assets around the world, making the awards more enforceable than any court judgment against a sovereign.

The arbitrators’ power — and by extension foreign companies — can get hidden or drowned in legal details, especially by lawyers who promote investment treaties.

I highlight 10 points below that give a sense of how far this power would go, using the TPP as an example.

1. After a TPP lawsuit is filed by a foreign investor, the arbitrators can review almost anything Canada has done on behalf of its people. There would be complex exceptions in the TPP that safeguard aspects of Canada’s sovereignty, but generally the arbitrators’ power is very broad.

2. Foreign investors would be able to challenge — and TPP arbitrators could then review — a decision by a government, a legislature, or a court. The usual principles of Canadian law requiring such disputes to be decided in a Canadian court do not apply.

3. Foreign investor lawsuits are not limited to the federal government alone. The decisions of a province or a territory or by a municipal or First Nation council can also be challenged. In international law, all bodies that exercise public powers are part of Canada as a unified entity.

4. TPP arbitrators would operate at a different level from Canadian courts. A decision by a court is a sovereign act of Canada. Thus, all court decisions would be subject to final review by TPP arbitrators, if challenged by a foreign investor.

5. TPP arbitrators would not be limited by Canada’s constitution or other parts of Canadian law. They would be subject to the TPP and relevant rules of international law.

6. To a far greater degree than other treaties — on human rights, anti-corruption, or the environment, for example — trade deals like the TPP lay out elaborate rights for private parties (here, foreign investors only) in clear, binding language and they make those rights highly enforceable.

7. Treaties like the TPP describe foreign investors’ rights in vague language, which arbitrators have often interpreted broadly as a basis for compensating a foreign investor.

8. TPP arbitrators would largely be a power unto themselves. Their awards are subject to little or no review in any court. In some cases, they can be reviewed on limited grounds by a panel of other arbitrators chosen by the president of the World Bank in Washington, D.C. In other cases, they can be reviewed on limited grounds in a court, albeit typically in a place chosen by the arbitrators themselves.

9. If Canada did not pay a TPP award, a foreign investor could take the award to other countries that have agreed to enforce arbitration awards in other treaties. The most important of these other treaties — the New York Convention of 1958 and the Washington Convention of 1965 — were originally created to back up arbitrations under contracts, not trade deals.

10. TPP arbitrators would have the power to order countries to pay backward-looking compensation to foreign investors. That is, the compensation against a country is calculated from the time of the country’s original decision that is later found to have violated the treaty. It is not calculated from the time of the arbitrators’ decision itself. So, countries can rack up massive liability without knowing if the original decision actually violated the treaty. This can give powerful leverage to large corporations with deep enough pockets to fund a TPP lawsuit.

Since the early 1990s, foreign investor lawsuits have led to billions of dollars in awards against countries.

On the other hand, a foreign company could not itself be sued and ordered to pay Canada under the TPP. The trade and investment treaties are structured one way. They give exceptionally powerful rights to foreign investors without any actionable responsibilities.

This imbalance is a political choice.

Any treaty can be written to put enforceable responsibilities on foreign investors; for example, to avoid corrupt activities or respect workers’ rights. But the governments driving the treaties — in Washington and Brussels but also Ottawa — have not done so.

Gus Van Harten is a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School and the author of Sold Down the Yangtze: Canada’s Lopsided Investment Deal with China (Lorimer, 2015).

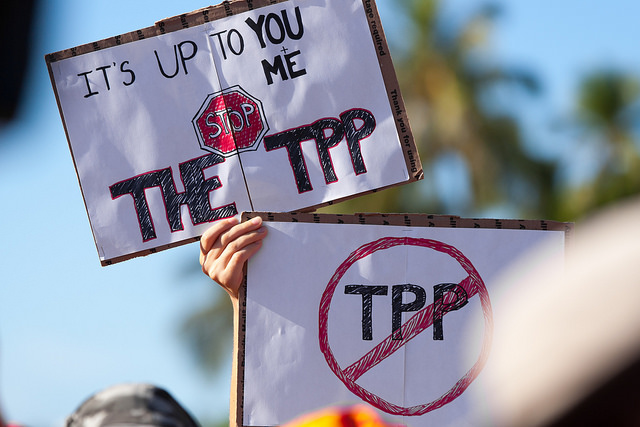

Photo: flickr/ SumOfUs