On June 8, 2012, World Ocean’s Day, I was fortunate to attend the eighth annual Elizabeth Mann Borgese Ocean Lecture, Blue Planet Under Threat: Challenges and Opportunities at Rio +20. The world’s oceans were not so fortunate — on that day or any other recent one.

Elizabeth Mann Borgese was the youngest daughter of Thomas Mann. After a tumultuous youth in which the family fled Germany after Hitler came to power, and a stint in the United States as an editor and researcher, she came to Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia as an internationally recognized authority on the Law of the Sea. An early environmentalist, Mann Borgese was also a founding member of the Club of Rome. Since her death in 2002, Dalhousie has continued to honour her contributions through a lecture series intended to “create dialogue and stimulate discussion about global ocean issues and the implications for the future of the oceans.”

Panelists Awni Benham, president of the International Ocean Institute (IOI) and former Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations; Susanna Fuller, coordinator of the High Seas Alliance; Member of Parliament and NDP environment critic Megan Leslie; David MacDonald former MP and lead Parliamentary advisor to the Canadian delegation at the 1992 Earth Summit; and Larry Hildebrand with the Marine Affairs Program of Dalhousie University, outlined a bleak story of four decades of failure to substantively address the threats to the blue planet since the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden.

An equally bleak vantage is provided in survey conducted by a group of internationally renowned ocean experts (Liane Veitch, Nicholas Dulvy, Heather Koldeway, Susan Lieberman, Daniel Pauly, Callum Roberts, Alex Rogers, and Johnathan Ballie) entitled Avoiding Empty Ocean Commitments at Rio +20. The authors discuss the many targets related to sustainable fisheries and protection of the marine environment that have successively been laid down by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982, Agenda 21 of the United Nations Earth Summit in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (the original “Rio)”, and the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation (JPOI) in 2002. They conclude that, “Unfortunately, implementation of many of these commitments has been difficult, ineffective, or practically nonexistent.” Liane Veitch and her colleagues turned their attention to five areas:

1. Sustainable Management: It is recognized that an overcapacity of fishing fleets exists and too much fishing activity is occurring. Despite a target of 4.02 billion kW days [kilowatt days are a slightly arcane measure of fishing capacity based on the engine power of fishing vessels in kilowatts and the number days they are engaged in fishing activities] set by JPOI in 2002, fishing capacity has actually increased to 4.35 billion kW days in 2010, an eight per cent rise. Current global fisheries catches are between 17 and 112 per cent higher than sustainable levels, and 30 per cent of fish stocks in the world are classified as overexploited, depleted, or recovering.

2. Fisheries Subsidies: Fishing capacity subsidies, which in 2003 were worth USD $16.2 billion, continue to drive over-exploitation of fish stocks. Despite a decade of efforts within the World Trade Organization (WTO), there has been a failure to achieve a consensus on reducing them. Veitch and her colleagues urge that, “Harmful subsidies should be phased out by a set date or redirected into beneficial fisheries management plans.”

3. Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing: Recent estimates (2008-1010) are that illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is worth on the order of USD $23 billion a year. It undermines fisheries management, harms both target and by-catch fish stocks, and steals revenues from legitimate fishers and governing bodies. In areas such as the west coast of Africa, there is little regulation, little chance of being caught, and hence little incentive not to continue poaching. Veitch and her colleagues recommend that “Widespread monitoring, control, surveillance, and enforcement of vessels at sea and increased uptake of catch and trade documentation schemes are required.”

4. Marine Protected Areas: In 2010 only 7.2 per cent of territorial waters and 1.6 percent of the total ocean lay within marine protected areas (MPAs). This is despite the fact that in 2002 the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) set targets for 10 per cent of marine areas to be protected by 2012 (now been extended to 2020 since it is clear the 2012 target will not be met). Even more coverage has been called for by the World Parks Congress, which has advocated that 30 per cent of the oceans to be protected by 2030.

5. Protection of Marine Biodiversity: The Global Marine Species Assessment (GMSA) is currently assessing the extinction risk of 20,000 marine species including marine mammals, sea turtles, sharks and rays, sea snakes, corals, mangroves, sea grasses, tunas, billfishes, as well as several fish families. As of 2011 over 10,500 have been assessed, and of these 15 per cent show an elevated risk of extinction (i.e., they are critically endangered, endangered, or vulnerable).

Furthermore, a comprehensive survey spearheaded by Stuart Butchart of the United Nations Environment Program and 44 of his colleagues, found that almost every indicator of biodiversity — of all species of plants and animals in the world — “showed declines, with no significant recent reductions in rate.” Veitch and her colleagues point to a few isolated bright spots, for example decreased threats to pelagic birds such as albatrosses and petrels, but the overall picture is dark and growing darker.

Is there any hope on the horizon? Despite the difficult, ineffective, or nonexistent implementation of past commitments, the June 20-22, 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (a.k.a., Rio +20) presents an opportunity for the world’s nations to turn the corner on the legacy of lofty intentions backed-up by vacuous measures. Veitch and her colleagues call on governments to honour their commitments to a sustainable marine environment by:

(i) reducing global fishing effort;

(ii) redirecting harmful subsidies towards improved management and protection; and

(iii) implementing an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (EAF) that protects vulnerable species.

They point out that Rio +20 provides an opportunity to “launch a negotiation process for a new implementing agreement under UNCLOS, seen as a key element for the protection and conservation of biodiversity on the high seas.” In other words, if these goals are not implemented within the legislative framework of the Law of the Sea — providing concrete measures and teeth to back up the desired objectives — their realization will remain as elusive as ever.

And indeed, at Rio +20 oceans are one of the ten “critical issues” which are being considered by the conference. The current draft of the Rio +20 resolution contains a section on oceans, including clause 163 that states:

“We recognize the importance of the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction. We note the ongoing work under the UN General Assembly of an Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group to study issues relating to the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction. Building on the work of the ad hoc working group and before the end of the 69th Session of the United Nations General Assembly we commit to address, on an urgent basis, the issue of the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction including by taking a decision on the development of an international instrument under UNCLOS.”

The key is the commitment — and on an urgent basis — to “the development of an international instrument under UNCLOS,” in other words an implementing agreement within the context of the Law of the Sea. This is absolutely necessary for lofty language to move beyond empty rhetoric, and it is important to note that such implementing agreements can only be negotiated at such international fora. A ray of light appears to be shining through the gathering darkness.

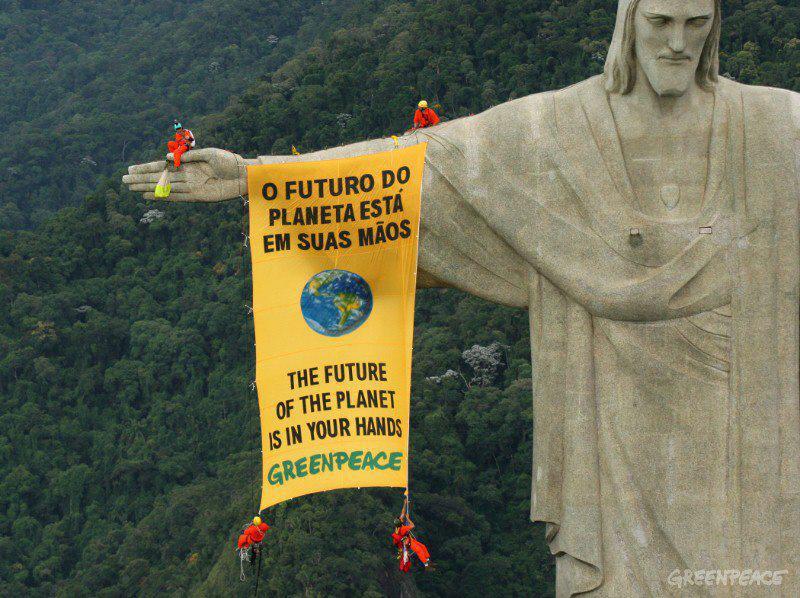

And indeed, non governmental organizations (NGOs) such as the High Seas Alliance [a coalition of 22 organizations concerned with marine biodiversity such as the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Commission, Birdlife, Ecology Action Centre, Greenpeace, International Program on the State of the Ocean, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Marine Conservation Institute, Migratory Wildlife Network Natural Resources Defense Council, Oceana, OceanCare, Pew Environment Group, Pretoma, Sargasso Sea Alliance, Tethys Research Institute, Turtle Island Restoration Network, Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, Wildlife Conservation Society, World Commission on Protected Areas, and World Wildlife Fund] have glimpsed the light. They have been urging the states attending the Rio +20 summit to “take urgently needed action to improve the rules and regulations that govern the high seas. Inclusion of text on a new implementing agreement under UNCLOS … demonstrates unprecedented and crucial political will to address failings of the current regime for managing activities with a potential to adversely impact the ocean beyond national jurisdiction.”

Moreover, most of the nations attending Rio +20 are supportive of the proposal. The 27 member states of the European Union are in favour; the G-77, a loose coalition of developing nations (originally 77, now including 132) including virtually all of the countries in South and Central America, Africa, the Middle East, Far East and Southeast Asia support the proposal; the 52 member nations of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) also strongly support the proposed measures. So that leaves only … Canada, United States, Russia, Japan, and Venezuela who oppose the proposal, and only Canada and the United States are vociferous in their opposition. Reached in Rio at the conference, Susanna Fuller, coordinator of the High Seas Alliance, said:

“A new treaty for high seas protection would be a game changer for the future of our ocean and the millions dependent on it for their survival. However, Canada is one of a handful of countries currently blocking this critical measure. We’re surprised that Canada has been so immovable on this issue given its historical support for the UN Law of the Sea Convention, the UN Fish Stocks Agreement, and the Convention on Biological Diversity. Their position is a major departure from the past.”

Fuller added that an implementing agreement would be the key in establishing high seas marine protected areas, environmental impact assessments, and access and benefit sharing to marine genetic resources. In contrast to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio where Canada, under then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, played a leading role in moving the agenda of the conference and successfully stewarding the Convention on Biological Diversity into existence, at Rio +20, Canada’s role under Stephen Harper has become that of a chief saboteur and leading obstructionist to environmental progress.

When asked by Anna Maria Tremonti on June 19, 2012 on CBC radio’s The Current, as to what Canada should be doing at Rio +20, environmentalist, Green Party leader, and Member of Parliament Elizabeth May replied, “The most helpful thing we could do is not go. In international fora Canada plays the role of undermining the strength of agreements. Under Stephen Harper our role in international meetings has been to sabotage progress that others want to make.” David MacDonald, a key Canadian player at the 1991 Earth Summit concurred saying “[Canada is] undermining, obstructing, and trying to weaken things. Canadians need to be aware of how much damage [the Canadian government] is doing behind the scenes.”

Let me close on a personal note: in 1977 I was a researcher working on a Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) project studying the collapse of the Peruvian anchoveta fishery. Insufficient regulation, excessive quotas, and the growth of fishing fleets and fishing effort combined with an El Niño weather phenomenon in 1972 causing the anchovy fishery to crash from a catch of 10.2 million tonnes to 4.4 million tonnes, a catastrophic 57 per cent decline in one year. By 1977 catches were down to 1.4 million tones. Beyond the ecological consequences that rippled through the entire marine ecosystem, the economic and social costs were enormous. The anchovy fishery, which was the second largest generator of foreign exchange for the Peruvian economy (after mining), saw its financial contribution cut by 87 per cent. The number of fish plants was cut in half, the number of fishing boats reduced by 47 percent, and employment in the fishery fell by 52 per cent. The poverty and unemployment caused by this collapse was palpable in the streets of fishing ports such as Chimbote, Callao, and Trujillo as I walked through the towns.

Without sustainable fisheries management policies and a truly ecosystem approach to fisheries, without the phasing out fisheries subsidies, without better control of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fisheries, without boosting the extent of marine protected areas, and without serious protection of marine biodiversity, the impoverished ecosystem, damaged economy, and suffering society that I witnessed in Peru in the 1970’s will become an ever more regular occurrence. In 1977 the Canadian government played an active and constructive role in helping to understand and remediate such disasters (the Peruvian anchoveta fishery has now, thankfully substantively recovered with fishing effort at much more sustainable levels). In 2012 the Canadian government is doing everything it can to be an impediment to progress and solutions.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.