Like this article? Chip in to keep stories likes these coming.

Our senses have a wonderful and wicked ability to take us different places, and food creates associations in powerful and sometimes surprising ways.

I think that most privileged people like myself can classify their food associations as either positive or historical: special meals, backpacking abroad, or maybe a particularly unsatisfying meal from our past. For example: “shipwreck,” the leftovers-on-leftovers stew my dad used to make, which I haven’t been subjected to in probably close to 20 years. And this is an important point: privilege means choice; and it means that a lack of choice is self-imposed or in our rear-view mirror.

I spent a couple weeks canoeing last summer, some of it in Temagami, just before I started working at an emergency food hamper program. At the time I was unemployed. In other words, going on an extended canoe trip was not the smartest idea, finance-wise, but my friend and I committed to doing the trip as cheap as possible, right down to the food we packed into our waterproof barrels.

And so, because we could get the ingredients basically for free, we spent the week eating a strange mix of quinoa, lentils, sesame oil and soy sauce — except for a couple of cans of herring, which I recall thinking at the time was the most delicious food in the all time history of food.

Fortunately, I think, I don’t often eat that peculiar mix of sesame and soy sauce. On the one hand, it reminds me of a beautiful trip in Northern Ontario. But on the other hand, I am taken back to what it felt like to have no choice — by choice, mind you — and my stomach turns and constricts at the thought of eating more of it. You have to eat on a canoe trip if you want to keep canoeing, even if it’s what you ate for lunch, and for breakfast, and for supper, and for lunch, and for breakfast. It’s sesame and soy sauce all the way down!

Choice and meaning and food

What does food mean? Maybe that sounds like a silly or incoherent question. Food means calories, sustenance, survival. It means community, history, tradition. Food is food. My guess is that choice (or its absence) makes a big difference in how we all think about food.

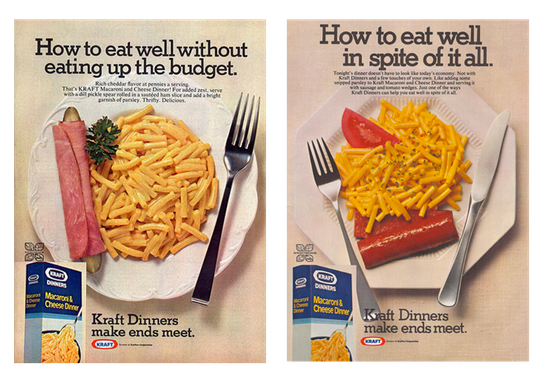

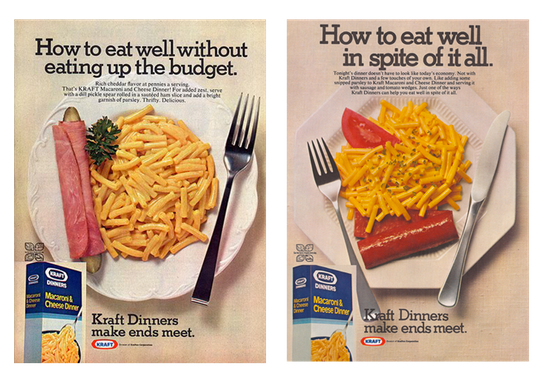

In their 2009 paper, University of Calgary researchers “contrast[ed] the perceptions of Canadians who are food-secure with the perceptions of Canadians who are food-insecure through the different meanings they assign to a popular food product known as Kraft Dinner.” To do this they interviewed Canadians, individually and in groups.

We give out a lot of Kraft Dinner (KD) at our food hamper program. Until last week, it was one of the few constants in our warehouse — we’ve run out of everything else, at some point, for some time, in the year I’ve been here. If they want it, every one or two person household receives some set amount of KD or some flavour of its generic imitators. Last year 13,974 of our hampers went to single people. According to my quick-math, that equals about 44, 880 boxes of KD, worth about $56, 997 according to current market rates.

How does your KD taste?

However, these numbers are probably too high, because — whowouldaguessed!? — KD is not one of our more popular food items. For many, KD is often among the items they return or they do not request it in the first place. Again, the Calgary study: “our thematic analysis shows food-secure Canadians tend to associate Kraft Dinner with comfort, while food-insecure Canadians tend to associate Kraft Dinner with discomfort.” This was true regardless of the source of the KD: whether or not food insecure people were buying KD at the end of the month, or receiving KD from food banks, they associated KD with discomfort.

The researchers identified a few different reasons for these divergent views. Food secure people choose when to eat KD, and when they do, they prepare it with milk and butter and all the KD fixins. From this perspective, KD is a wonderful, inexpensive, warm and comforting meal-in-a-box. Food insecure people — especially those relying on assistance from programs like ours — are rarely choosing to eat KD, and often prepare it without milk or butter. Again, my supporting evidence is mostly anecdotal: milk is one of our most precious commodities, meaning we can rarely include it in hampers for one and two person households. Which are the only households that receive KD at our program.

If I had a million dollars, would I eat more KD?

These different perspectives matter; they are not simply a matter of agreeing to disagree. They matter because the food secure group is much more likely to shape or determine the food insecure group’s choices. Food secure folks donate to food banks, like ours, which support food insecure folks. And it is most typically food secure folks who are in decision making positions in the existing food system. The study concludes, “ignorance among food-secure people of what it is like to be food insecure…partly accounts for the perpetuation of local food charity as the dominant response to food insecurity in Canada.”

This seems right, based on my own experiences. At the same time, however, it’s also true that “the fact that food banks are entrenched in our society speaks strongly to the compassion, caring and commitment of more privileged Canadians to not let people go hungry. That act speaks to a phenomenal sense of social responsibility and concern around this issue.” Yes, we are ignorant, but I know many thoughtful people who support programs like ours, and who do try to put themselves into food insecure peoples’ shoes. Indeed, the researchers interviewed many donors who described imagining a food insecure perspective when it came time to donate. One interviewee, a union official said: “You might serve it to your own kids, to your own family, or even to yourself. In the end, you make it yourself.”

I’d eat KD, I do eat KD, I enjoy KD. If it’s good enough for me, surely it’s good enough for food insecure folks? This is a good thought, and a valuable principle: don’t give what you wouldn’t eat yourself. But it’s not quite a good enough thought, because, remember, “Kraft Dinner “tastes” entirely different, depending upon whether a given box ends up being consumed in a food-secure or in a food-insecure household.”

(Mis)understandings and charity

There is a deeper point here: it looks like we can’t ever quite accomplish the proverbial mile walked in someone else shoes. The discussion above outlines some of the dangers of thinking we can, or that we have truly put ourselves in their shoes.

And finally, doesn’t this tension — between wanting to help but struggling to imagine strangers’ circumstances — just reveal the limits of charitable work? I don’t think it is theoretically impossible to understand another person’s situation enough to help them. But in most straightforward charitable models, the odds are stacked against us. This is an old point, but worth restating. Charity involves an imbalance of power: one vulnerable group depends on the arbitrary benevolence of another, more powerful group; and this relationship is typically not reciprocal. (There’s of course nothing inherently wrong with an asymmetrical relationship, only when it consistently tilts in one direction, or consistently harms the same group.)

Some affluent people have the opportunity to work alongside people quite differently situated than themselves. But most do not; and food hamper programs like ours depend on donations, typically from individuals and corporations whose knowledge of our situation is — how ever well intentioned — problematically incomplete. Tricky at the best of times, the power imbalances in a charitable model compounds the difficulties involved in trying to determine what’s best for another person.

What about solidarity?

Those power imbalances do not disappear easily or quickly, but as communities work together in solidarity, they may be able to avoid some of the problems I’ve identified. This is a huge idea, and deserves a more extended discussion (coming soon!). There are, however, a range of organizations and/or communities tackling food (in)security in ways that are more solidaristic, or less charitable — ways that democratically involve low and high income folks from the start, which proceed from the ideas that power should be shared, and that all members of a community can meaningfully contribute to community life. We continue to help over 130 families a day with emergency food, and I keep trying to remember what soy sauce and sesame oil tasted like on day seven.

* From The Encyclopedia of Food and Culture: ‘‘In essence, ‘‘comfort food provides individuals with a sense of security during troubling times by evoking emotions associated with safer and happier times’’ (in Locher 2005, 14:3).