COVID-19 cases are going up rapidly in most of Canada. The biggest and most worrisome increases are happening in British Columbia, Alberta, and, especially, Ontario.

Health officials in Ontario say the province has not had it so bad since the beginning of the pandemic. On Friday, April 16 they reported over 4,800 new cases in Ontario.

Hospitals in large cities such as Toronto and Ottawa are at capacity, and medical authorities now talk about the potential need for rationing. They anticipate having to triage patients — having to practice a kind of battlefield medicine, by deciding who gets treatment and who does not.

By contrast, in Quebec — which is still the province with the most cases per million cumulatively since the beginning of the pandemic — the current rate of increase is not nearly as severe. Quebec reported a bit more than 1,500 new cases on Thursday, about a third of Ontario’s new cases.

Each day, Ontario has been adding about 30 new cases per 100,000 people of late. For Quebec, that figure is only 20 per 100,000.

Quebec’s curfew and an Ontario slow to act

These figures could change, and quickly. We have seen that happen throughout the pandemic. But, for now, some experts in Quebec are seeking to understand what their province might have been doing right over the past four or five months; and what their neighbour could have been doing wrong.

One big difference between the Quebec and Ontario approaches is a curfew. Quebec has one — or, more precisely, different ones for different regions of the province. Ontario does not.

Many Quebecers have been unhappy with the curfews, which are as early as 8 p.m. in some parts of the province. But Quebec Premier François Legault ardently defends them. And he may have a point.

Experts, such as Roxane Borgès Da Silva, a professor at the University of Montreal’s School of Public Health, argue that the Quebec curfew has been successful in curtailing gatherings among young people. Such gatherings have been the sources of major COVID-19 outbreaks over the past 13 months.

But the curfew is only one measure, and it is difficult to calculate the impact of a single rule or regulation. What might be more significant is the relative slowness of the Ontario government response to the virus’ third wave.

Early in January, when the vaccine rollout was barely getting underway and cases were going up, Ontario lagged behind Quebec in imposing new limits on social interaction, such as shutting down non-essential businesses.

Borgès Da Silva points to the Ontario government’s decision, immediately after the Christmas holidays, to allow restaurants and bars outside of Toronto and vicinity to re-open. She told the Montreal newspaper Le Devoir the Ontario approach might have been “too radical.” Quebec, she says, tried to re-open more gradually, to allow life to return to normal “a bit more” — but within a framework of continued restrictions.

Different vaccination strategies; paid sick leave

Quebec was also faster in getting its people vaccinated than Ontario, which is due, in part, to Quebec’s more centralized approach.

The Ontario government has, in essence, sub-contracted vaccine distribution to local governments. In Quebec, the provincial government has maintained far more control.

Part of Quebec’s strategy has included making early and widespread use of local pharmacies. Quebec did not severely limit the number of pharmacies which could give the vaccine and did not ordain that pharmacies could only get access to the AstraZeneca vaccine — as did Ontario.

As well, the Quebec health ministry could call on the full collaboration of its extensive network of local community health and social service centres, the so-called “CLSC” system. There is no counterpart to that system in Ontario.

Quebec also chose, at the outset, to delay the second dose of the vaccine, allowing the maximum number of people possible to get the all-important first dose. Other provinces, including Ontario, followed Quebec’s lead on this, but took their time to do so.

Then, there is the contentious issue of paid sick leave.

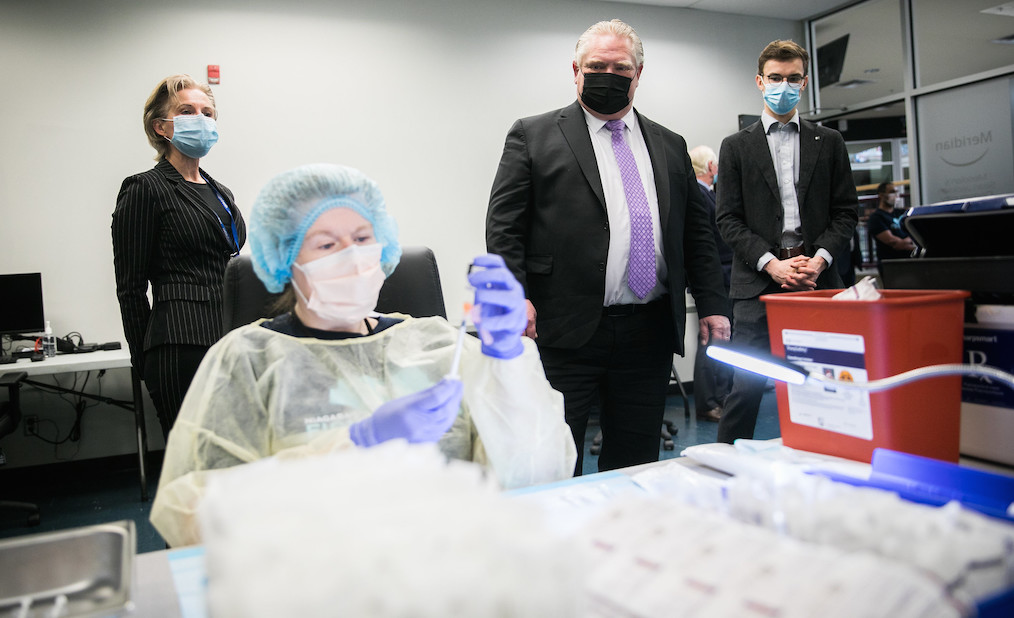

Health-care professionals in Ontario continue to try to convince the provincial government to enact a generous paid sick leave program. The Doug Ford Conservatives went in exactly the opposite direction after they took power. They abolished the modest two days’ leave the previous Liberal government had instituted.

Quebec’s sick leave provisions are not perfect, but they are better than Ontario’s.

Quebec is the only province with paid family leave — leave to care for a sick family member — and the only province that provides a financial benefit for workers who have to isolate because they have COVID-19 or have been in contact with someone who does. That payment of $575 per week, for up to 14 days, goes to workers whose employers do not provide a comparable benefit.

Ontario’s Premier Ford refuses to accept the medical community’s near unanimous view that workers in key and essential sectors, such as food processing, warehouses, and long-term care, have been going to work sick and spreading COVID-19. For lack of guaranteed paid leave, those workers simply have no choice.

In Ontario, COVID-19 outbreaks at facilities such as Amazon distribution centres and Cargill meat-packing plants have been severe. Medical experts are convinced sick employees in such workplaces have gone to work notwithstanding their symptoms.

The medical experts’ prescription for that syndrome is simple: paid sick leave for the workers. It would be the only way to keep the COVID-afflicted workers home, they say.

The Ontario premier hides behind the fact that the federal government has used its limited authority to leap into the breach with its own modest 10-day sick payment. Workers must apply for that payment, however, and they only get it weeks or months after their illness. It is not a replacement for guaranteed sick leave, with full pay.

As well, not long after taking over government, Ford and his team took the axe to Ontario’s public health infrastructure.

Those cuts constituted an overtly partisan and political act. In announcing his intentions to slash funding for local public health units, in particular Toronto’s, Ford characterized Toronto Public Health as a “bastion of lefties.” So much for evidence-based policy making.

Resistance to these announced cuts was swift and widespread, and Ford backed down, but only partially. He still cut vital public health services, which resulted in the departure of key people, and general demoralization in the sector.

And those cuts happened just when the people of Ontario would need their public health services more than ever.

Karl Nerenberg has been a journalist and filmmaker for more than 25 years. He is rabble’s politics reporter.

Editor’s note, April 16, 2021: This story was updated to provide COVID-19 case numbers in Ontario released on Friday, April 16.

Image credit: Premier of Ontario Photography/Flickr