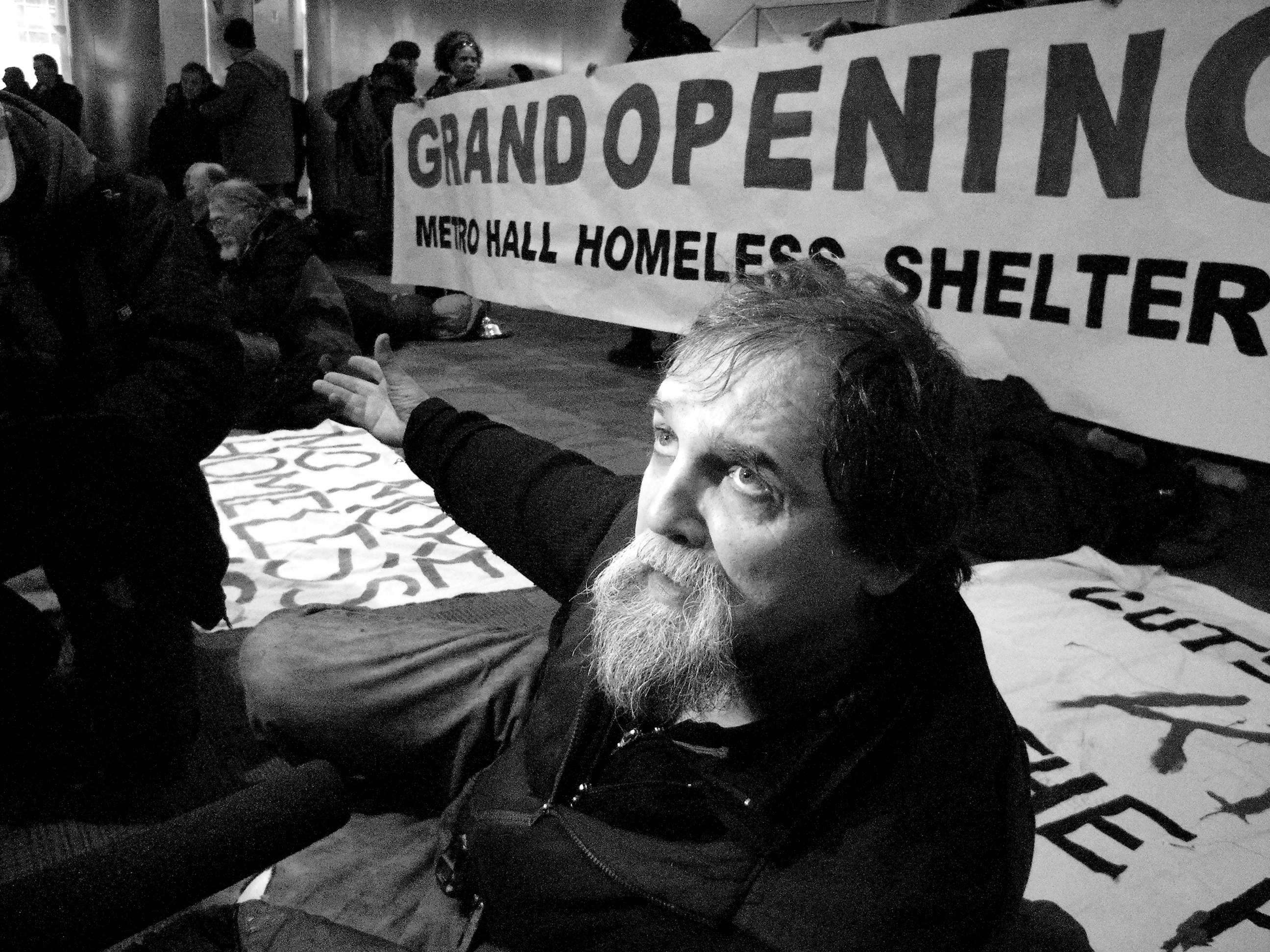

Seven sleeping bags and a rolled up mattress sat under a banner that read, “Grand Opening Metro Hall Homeless Shelter.”

After a motion by Toronto city councillor Adam Vaughan to debate the need for more emergency beds in the shelter system was defeated on February 20, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) announced that they would be opening up an emergency shelter at Metro Hall on March 7.

That day had arrived.

It was an overcast, drizzling morning outside Metro Hall in downtown Toronto. Dozens of media assembled on the sidewalk outside the 55 John Street entrance.

“We have a serious crisis on our hands in the shelter system,” said Gaetan Heroux, an organizer with OCAP.

“The Good Shepard was packed last night. The Gateway was packed last night.”

Most of the Out of the Cold programs will shut down within a few weeks. These volunteer initiatives, run mostly out of church basements, provide a meal and a bed for homeless people from the beginning of November to the end of March.

“Where will those people go?” asked Heroux. “What happens when you run shelters at over 90 per cent capacity?”

Heroux said that several years ago city council decided that the shelter system should not exceed 90 per cent capacity.

“So why is hostel services constantly running (now) at 96 or 97 per cent and often at 100 per cent?” asked Heroux.

“Why aren’t they opening up Metro Hall?”

In the summer of 1999, Heroux said the head of hostel services opened up Metro Hall as an emergency hostel.

Without requiring approval from city council.

“For three weeks, 150 homeless men and women were coming here because there was nowhere to go,” said Heroux.

“During heat alerts Metro Hall opens up as a cooling centre.”

Overcrowded shelters often lead to abnormally high levels of stress and episodes of violent behaviour, forcing many to abandon the shelter system and take their chances on the streets.

Often with deadly consequences.

In the winter of 1995-96 three homeless men, Eugene Upper, Irwin Anderson, and Mirsalah-Aldin Kompani, froze to death on Toronto’s streets.

“At the inquest they said there were beds available when those men froze to death,” said Heroux. “But two days after Irwin Anderson died, the city opened up the Moss Park Armoury.”

So it’s not just an issue about available beds.

“You have to be able to go somewhere where you feel safe and you have room to move,” said Heroux.

OCAP and their allies made their way to the front door of Metro Hall surrounded by a throng of reporters and photographers.

Building security wouldn’t allow sleeping bags or mattresses inside the building.

Once inside, the crowd made its way to the large, open space facing King Street. One by one they removed their jackets and sat down on the floor in front of the Grand Opening Metro Hall Homeless Shelter banner.

A few people with the sleeping bags managed to make their way into Metro Hall through a secondary entrance.

They were attacked by overzealous security guards who tried to wrestle away their sleeping bags. Police stepped in and quickly de-escalated the situation.

There were no arrests and the sleeping bags were not confiscated.

Outreach worker Richard Dalton shared his thoughts on why city council and OCAP have radically different versions on the shelter bed situation in Toronto.

“We’re counting people while city council likes to count beds or statistics,” said Dalton.

“If the shelters are running at 96 per cent capacity that is still unacceptable. Yet the city thinks if there is still 4 per cent available, we don’t have to do anything.”

But the problem with that line of thinking, said Dalton, is that the 4 per cent could mean only women’s beds available or no women’s beds available.

Or the downtown shelters may be full, but there are still empty beds in the suburbs.

“People that are actually on the ground or in the streets know that there’s always people waiting at the Peter Street referral centre,” said Dalton.

On Wednesday, Dalton went to every lunch meal program downtown, talking to people about their struggles getting into a homeless shelter.

“At 96 per cent capacity, you end up with TB, bed bugs,” he said. “We have photographs of blood stained walls. So the conditions in an overcrowded situation are not healthy.”

And the competition for shelter beds is so stiff that the people get bullied out of shelter bed lineups.

“The 96 per cent city number is already an intolerable, overcrowded situation,” said OCAP organizer John Clarke.

“What it doesn’t tell though is how many people were turned away at 8 pm, if the city polls the shelters at midnight or 1 am. By the time these few beds become available, it’s too late.”

At a noon hour press conference, Mayor Ford dismissed Thursday’s action at Metro Hall, calling it a cheap, attention getting publicity stunt by OCAP.

“He thinks that John Clarke and OCAP are lying,” said Liisa Schofield, an OCAP organizer. “He thinks that the 3 to 4 per cent available beds should be enough.”

Ford also said that it’s the city’s policy to never turn someone away.

“We dedicate an enormous amount of resources to our shelter system,” said Ford. “OCAP is wrong about budget cuts to shelters.”

OCAP quickly responded to the Mayor’s accusations.

“So why if there are empty beds are people sleeping in chairs or on the floor?” asked Heroux.

“We are asking for a temporary emergency shelter to be set up. We know that this place can’t function as a permanent shelter.”

Brian DuBourdieu spent over a decade living in shelters and and witnessed the violence that develops in when they become overcrowded.

“I’ve seen people bricked, knifed, mentally tormented and beaten up in fist fights,” said DuBourdieu.

“There might be two beds, but if they’re in a youth shelter that’s no good for a 55-year-old man.”

DuBourdieu challenged the Mayor to spend two nights in a shelter to find out for himself how bad things really are.

He also invited shelter staff to come down to Metro Hall and speak to reporters about the conditions in their shelters.

Criminal lawyer Sarah Shartal, who works with clients dealing with addictions and mental health issues who are also homeless or precariously housed, has clients that could be released from jail today on bail programs if there was an address.

“But because there are no beds and no guarantee of an address, they stay in the Don Jail or east and west detention,” said Shartal.

“So those who can’t get beds are warehoused in jails.”

Two years ago, if she wanted to get someone out on bail, Shartal could find a bed.

“I’m a lawyer,” she said. “I’m not supposed to be calling shelters at 7:30 am. But now we have to.”

Since 2006, frontline worker Zoe Dodd said almost 300 beds have been lost from the shelter system. She knows lots of women who are trying to get off the streets and into a shelter but can’t because there are no women’s beds available.

“We’re not leaving said,” Schofield.

“This shelter has been established. We’re here all night. We’ll be back here tomorrow.”

Police moved in around 10 pm and started escorting people out of Metro Hall. One person was arrested. The rest were issued tickets and will appear in court some time in April.