The first protest was a bucolic occasion. On June 6, after an energetic SaveOurPrisonFarms rally in a Kingston church, during which we were meticulously instructed in the behaviour expected of us during a peaceful protest, we ambled along in the sunshine, accompanied by homemade banners, a hay wagon pulled by a tractor, a contingent of smiling nuns, a donkey, and some kids dressed up as sheep and cows. The community — solidly behind our efforts — cheered us on.

We even did a tiny spot of civil disobedience as we walked up a driveway to Correctional Services headquarters and carefully taped our petition to the door, avoiding nails so as not to spoil the paintwork. The petition itself was a plea to the federal government not to go ahead with their scheduled closing of Canada’s prison farms — a vital element not only in local food chains but in the rehabilitation, mental health and socialization of minimum-security prisoners.

Nobody beat us up, arrested us or tear-gassed us. We did not set any cars on fire or break any windows. The Black Blockers who trashed downtown Toronto during the G20 would have thought us despicably wussy.

People are still poring through the fallout from that Toronto protest. Who did what, when, to whom and why? Why — knowing of the dangers of holding the G20 in a fenced-off, emptied-out downtown Toronto — did Prime Minister Stephen Harper not respond to Toronto’s pleas and change the venue? Why were legitimate NGOs blocked from access to the press, within the security-protected playpen? What accounts for the Ontario government’s confused instructions about security laws? Why the beat-up journalists? Why the nonchalance about the Black Bloc rampage? Why the wholesale roundups of bystanders?

And why the factory-chicken detention facilities for those corralled — scant food and water, no calls to lawyers and, if witnesses are any indication, nasty language and harassment? Is this “normal” — give a group unlimited, unsupervised power over another group, and this is what happens? If so, who authorized that power? Was the treatment of those arrested some sort of dry run — a testing of the waters to see how far those in authority can move toward Tinpot Dictatorship North, without a vote-losing backlash? Was the Black Blocker mayhem allowed so there would be a justification for the undue force later? And why is not a public inquiry in order?

At first glance, the Kingston protest and the Toronto one — and the very different responses to them — seem miles apart. Yet something unites them: They’re both about what kind of country we want to live in. They are about crime, or what is perceived to be crime, and they are about punishment, and what kind of punishment our society deems appropriate.

Let’s consider the context. With the secrecy and autocracy we are coming to expect, the federal government has moved to close down Canada’s long-running prison farms, and to implement a mega-prison system modelled on some of those in the United States. The overall plan — called “A Roadmap to Strengthening Public Safety” — has now been denounced by, among many others, Conrad Black. “It is painful for me,” he said, “to write that with this garrote of a blueprint, the government I generally support is flirting with moral and political catastrophe.” (As he points out, he’s not exactly your average bleeding heart.)

As for the Truth in Sentencing Act, the Parliamentary Budget Officer has produced an exhaustive report showing the government’s estimates of $2-billion in additional costs are way off — the PBO says the increase will be more in the range of $5-billion. It’s clear that neither the act nor the road map will do anything to decrease crime, but they will do everything to increase costs. Not “tough on crime,” but “stupid about crime,” as Jeffrey Simpson has written.

Are the government’s useless but expensive measures a job-creation gimmick: more prison guards? But once prisons are seen as an industry, prisoners become the raw material and must be constantly supplied. The methods for creating criminals are well known; they include poverty, lack of employment and education, dehumanized prisons where novice criminals may learn from experts, and the criminalization of petty offences. In the 19th century, the Australian penal colonies felt the need of more women for sex, so men were transported for hard crimes, but women for stealing a ribbon.

What are prisons for? Rehabilitation? Keeping us safe? Or harsh punishment, pure and simple? This Prime Minister has shown a suspicious interest in the infliction of pain. Remember his last election plan to lock up 14-year-olds convicted of serious crimes for life? His government doesn’t seem remotely interested in helping the incarcerated achieve productive lives. What sort of slogan does it intend to write above the doors of its mega-prisons? “Abandon Hope, All Ye Who Enter Here?”

“Bring your knitting,” the Kingston SaveOurPrisonFarms volunteers were told. “It will be fun!” That’s the Canada we thought we knew: civic responsibility, lending a hand, second chances. Which accounts for the outrage over the Toronto events: It was our image of ourselves that was attacked. The well-meaning knitter and jolly world-improver image got a boot in the face.

But that image could save us yet. Clap your hands if you believe in it — better still, vote for it — and maybe it will come to life again.

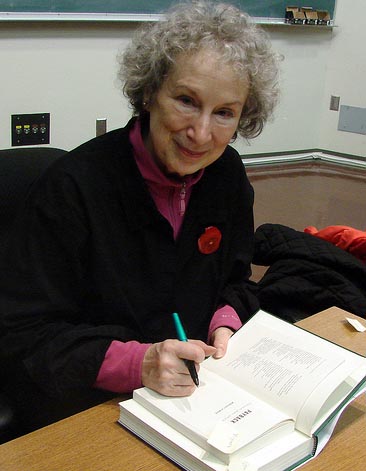

Margaret Atwood’s latest novel is The Year of the Flood. This article was first published in The Globe and Mail and is reprinted with the author’s permission.