Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

Christie Blatchford seems to have a penchant for horse manure. In her vitriolic piece about Attawapiskat Cree Chief Theresa Spence, who is entering the twenty-first day of hunger strike on Monday, Blatchford writes, “all around her, the inevitable cycle of hideous puffery and horse manure that usually accompanies native protests swirls.” In 2006, she wrote an equally disgraceful and racist puff piece equating Muslims with terrorism, deriding men in beards and women in burkas, declaring that the Islamic Foundation of Toronto “had a sea of horse manure emanating from the building.”

In her most recent piece, Blatchford has the audacity to refer to Chief Spence’s action as “one of intimidation, if not terrorism.” I am reminded of the words of Martin Luther King, “We who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to surface the hidden tension that is already alive.” Blatchford provokes further, “there is I think a genuine question as to whether there’s enough of Aboriginal Culture that has survived.” Wrong, Blatchford. Indigenous peoples, cultures and nations have survived and thrived despite genocide — despite a long, shameful and racist history of residential schools, forced sterilization, small pox and germ warfare, the breaking of treaties, legislative control including through the Gradual Civilization Act and the Indian Act, forced dispossession from lands and relocation to reservations, outlawing of ceremonies such as the potlatch and traditional activities such as fishing and hunting, and much more.

I will agree with Blatchford on one thing though, hunger strikes do indeed “have a way of reducing complex issues to the most simple elements.” An act of ultimate self-sacrifice, famed hunger-strikers such as Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, Bobby Sands, Khader Adnan, Cesar Chavez, Nelson Mandela, and Irom Chanu Sharmila persisted in their demand for the most basic of elements: land, life, abundance, freedom and dignity.

There is no end to the stupidity of Christie Blatchford

Blatchford’s recent piece is unsurprising given her history of sensationalist writing. Two years ago she released the oxymoronically-titled book Helpless: Caledonia’s Nightmare of Fear and Anarchy and How the Law Failed All of Us, arguing that the Ontario government and Ontario Provincial Police failed to protect the helpless and fearful settler Caledonians, who were victims of the lawless Native thugs of Six Nations (she doesn’t know to use Haudenosaunee people of the Grand River).

Conveniently, Blatchford glosses over the regular anti-Native violence and white supremacist organizing in Caledonia to reproduce racist tropes about the civilized settler in need of protection from the savage Native. Her book is devoid of any context of the over 150-year land dispute that has seen the current Six Nations land base represent less than 5 per cent of what is outlined in the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784 and she makes no mention of the over 29 land claims filed by Six Nations as the underlying reason for the land reclamation.

Last year Blatchford wrote about Attawapiskat, claiming “some First Nations haven’t a clue how to govern themselves.” More recently, she wrote about Wally Oppal’s Missing Women’s Inquiry report, audaciously stating this tragedy is not due to institutional and societal racism and sexism against Indigenous women. No, for Christie Blatchford the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women is due to the “broken state of Aboriginal culture… which is pathologically ill.” And just this week, Blatchford slams Aboriginal-specific fishing policies such as food, social and ceremonial fisheries for creating unfairness for non-native fisheries.

All three paternalistic diatribes paint settler society as victims, homogenize Indigenous communities as the Other who are culturally inferior and inherently backwards (a racist civilizing discourse that justifies imperialism locally and globally), and lay blame and shame on Indigenous communities instead of on colonial policies, institutions and relations.

There is much to criticize about what is happening in Attawapiskat, what transpired at the Missing Women’s Inquiry, and the conduct of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, but “lax” treatment of Indigenous communities is most certainly not one of them. Much the opposite — Attawapiskat was immediately blamed for its housing crisis and had to fight the imposition of Third Party Management at the Federal Court, the Missing Women’s Inquiry shut out Indigenous and Downtown Eastside women’s groups, and Indigenous communities such as the Sto:lo have been facing hundreds of criminal charges for exercising their inherent Aboriginal fishing rights.

Attitudes reproducing colonialism

So why bother rebutting a known racist who has a soapbox under the guise of journalism? Blatchford’s writings reflect an undertone that is omnipresent in all right-wing and anti-Native ideologies masquerading in comments such as “Natives don’t pay taxes and receive all kinds of special treatment,” “Natives should stop complaining and get a job,” “Natives are responsible for their own social condition on and off reserve,” and so on.

Such comments are embedded in and reflect deeply colonial attitudes in three main ways: they invisibilize the reality of genocide that has created the deliberate conditions of marginalization and impoverishment for Indigenous people, they propagate the idea that Indigenous communities need to assimilate into the dominant settler and consumerist way of life, and finally, such comments evade a discussion on how the theft and appropriation of Indigenous lands and resources subsidize the Canadian economy rather than the other way around.

Settler-colonialism has forcibly displaced Indigenous peoples from their territories, seeks to destroy autonomy and self-determination within Indigenous governance, and has attempted to assimilate Indigenous cultures and traditions. Settler-colonialism has been normalized to such an extent that, instead of revealing itself, it presents its victims and survivors as the source of their own problems.

Legislation entrenching colonialism

Chief Theresa Spence’s courageous hunger strike and others hunger-striking alongside her including Emil Bell and Raymond Robinson, as well as opposition to Bill C-45 and the other pieces of legislation, is about the impact of federal policy within an ongoing legacy of colonial relations. According to Mi’kmaq lawyer and scholar Pamela Palmater, “The creation of Canada was only possible through the negotiation of treaties between the Crown and Indigenous nations… The failure of Canada to share the lands and resources as promised in the treaties has placed First Nations at the bottom of all socio-economic indicators — health, lifespan, education levels and employment opportunities. While Indigenous lands and resources are used to subsidize the wealth and prosperity of Canada as a state and the high-quality programs and services enjoyed by Canadians, First Nations have been subjected to purposeful, chronic underfunding of all their basic human services like water, sanitation, housing, and education.”

Over the last four decades, and with greater urgency since the global financial crisis, there has been an emphasis by the Canadian government on converting reserve lands into fee simple lands (i.e private property), which would expedite extinguishment of Aboriginal title and the surrender of Indigenous lands. Russell Diabo, editor of First Nations Strategic Bulletin, extensively outlines how recent legislation is part of this trend of assimilation and termination. According to Diabo, “Termination in this context means the ending of First Nations pre-existing sovereign status through federal coercion of First Nations into Land Claims and Self-Government Final Agreements that convert First Nations into municipalities, their reserves into fee simple lands and extinguishment of their Inherent, Aboriginal and Treaty Rights.”

Fee simple property on reserve lands must be understood within capitalism and colonialism, which have been mutually-reinforcing processes to justify the illegal theft and expropriation of Indigenous lands. Championed by the likes of Tom Flanagan, former advisor to Stephen Harper and campaign manager for Alberta’s Wildrose Party, the privatization of reserve lands (what capitalists refer to as “dead capital”) and converting collectively-held land title into the legal regime of individual property rights is necessary in order to sell reserve lands to multinational corporations. This is part of a worldwide trend to impose market-driven and resource-extractive development on to Indigenous, peasant and rural communities through investment agreements and structural adjustment policies. Neoliberal economist and World Bank darling Hernando De Soto, for example, has been pushing fee-simple property ownership throughout the global South. Expressing opposition to such ideologies, Harley Chingee, a member of the First Nations Lands Advisory Board, is quoted as stating, “The change would undermine signed Treaties across Canada; undermine our political autonomy; restrict our creativity and innovation; and place us in a dangerous position where any short-term financial difficulty may result in the wholesale liquidation of our reserve lands, or the creation of a patchwork quilt of reserve lands like Oka.”

Idle No More and decolonization

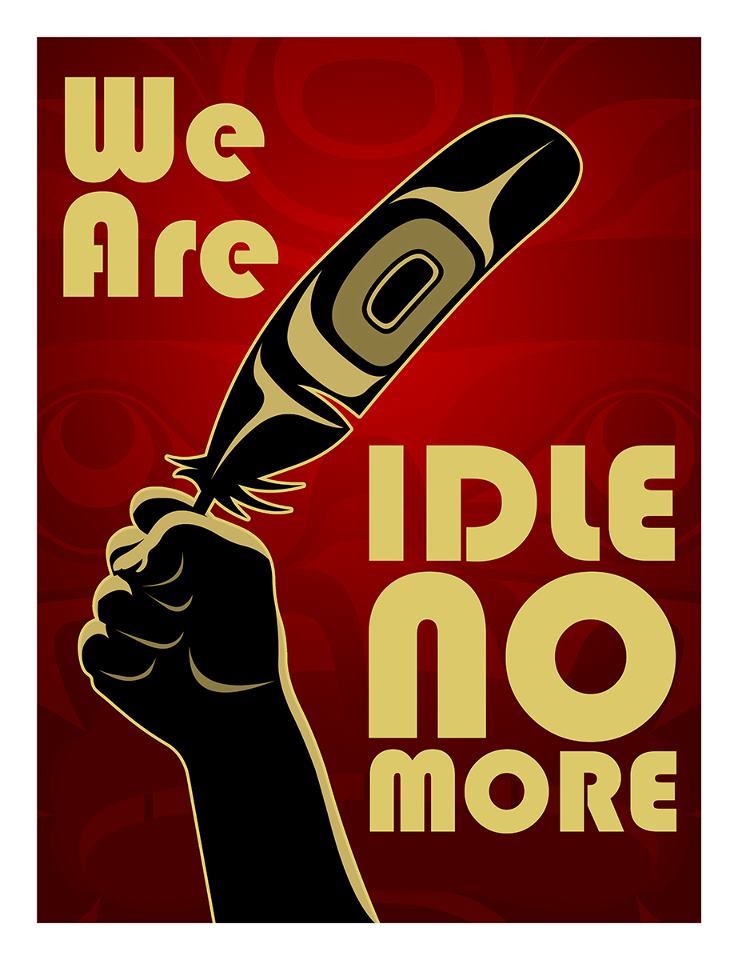

We know that Blatchford and other right-wing commentators and politicians are on the wrong side of history, where and how the rest of us will stand is the crucial question. The grassroots Idle No More movement — through rallies, blockades, social media, round-dances, and ceremonies — has inspired Indigenous communities as well as non-Indigenous allies across these lands. Jessica Danforth, multiracial Indigenous feminist, tells me that “Idle No More was started by Indigenous women who have never been idle. Idle no more isn’t just about Bill C-45; it’s also about supporting our youth, defending land, honouring the past and future seven generations and so much more.” Bonnie Clairmont, Bear Clan of the HoChunk nation (south of the colonial border) similarly says, “I’m reminded of how Indian women are strong because we protect our treaty rights, grandmother earth, resources, our children and our people.” Given that colonial violence has intentionally targeted Indigenous women, it is no coincidence that Indigenous women leading this movement is in and of itself an explicitly anti-colonial response.

Decolonization of settler-colonialism on these lands requires a commitment to fighting colonization, and a resurgence and recentering of Indigenous worldviews of another way of living and protecting the land. The obligation for decolonization rests on all of us. Indigenous Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson urges non-Natives to seriously take on the struggle against colonialism. “We don’t have to uphold this system any longer. We can collectively make different choices,” she writes. Stephanie Irlbacher-Fox similarly writes, “What it [Idle No More] highlights is that Harper’s extreme legislation is only possible because successive generations of settler Canadians have normalized looking to government rather than themselves to resolve “the Indian problem.” She further argues that “co-existence through co-resistance is the responsibility of settlers… Relationship creates accountability and responsibility for sustained supportive action.”

We must embody and enact decolonization in order to claim it. Decolonization is as much a process as a goal; the journey of how we get there, together, is as critical as the destination we reach.

As Native Youth Movement member Joaquin Cienfuegos notes: “We have to learn how to be human again, this battle is one where we not only decolonize ourselves and our minds, but decolonize our condition.”

Decolonization’s most transformative potential rests in freeing us all from a colonial and hierarchical relationship of domination, from a dehumanizing social organization that robs us from one another, and from a materialist political economy that destroys the land and our collective future.

Ultimately, decolonization grounds us in gratitude and humility through the realization that we are but one part of the land and its creation, that culture is not synonymous with capital or consumption, and that we can constitute our kinships and relations based on shared values of respect and responsibility to Indigenous communities, one another, and the land.

Harsha Walia (@HarshaWalia) is a South Asian writer and activist based on Vancouver, unceded Musqueam, Skwxwú7mesh, and Tsleil Waututh territories. She is involved in anti-racist, migrant justice, feminist, anti-capitalist and anti-colonial movements and has been active in Indigenous solidarity for over a decade.