On October 31 the labour movement in Canada received a most unwelcome Halloween gift from the Ford government in Ontario: they tabled Bill 28, An Act to Resolve Labour Disputes Involving School Board Employees Represented by the Canadian Union of Public Employees, barely a day after these workers had indicated their intention to go on strike after months of trying to bargain with the government. The legislation did not provide for binding arbitration as has happened with past labour disputes – it imposed a new collective agreement on workers for the next four years, with a wage increase well below inflation.

CUPE has never seen legislation like this in its almost 60 years of existence – “a stunning attack on us and on all those who depend on the Charter”, as the union termed Bill 28. Indeed, this legislation was unprecedented in the history of labour relations in Canada because it preemptively included the infamous Section 33 clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms – the notwithstanding clause. Section 33 deliberately allows a government to violate a right guaranteed by the Charter – “notwithstanding” that this would violate the 1982 Constitution Act (that’s the formal version of what we casually call the Charter) for a period of five years.

The Charter is celebrated for many things: for protecting many of the rights and privileges that had not previously been so codified, for giving us a unique and collective identity and even, sometimes for enabling (at least within the courts) the quests toward justice for many marginalized populations within Canada. The Federal Justice Department website terms the Charter “one of our country’s greatest accomplishments.” In particular, the Charter is supposed to protect the rights of various minority populations in Canada – it is a response to the deeply felt if sometimes fuzzy notion that the rights of minority populations cannot be at the mercy of the will of the majority (as expressed in electoral cycles).

The Charter is the giant red umbrella of my imagination under which all imagined Canadians are supposed to find protection from the most powerful forces in Canada – our governments at all levels. I’m not at all anti-government – I believe that government can be a force of good and should be a force that seeks to raise all of us up. But the truth is that the Charter is not absolute. For one thing, the very first bit of the Charter (Section 1) sets forth the conditions under which governments can limit our rights and freedoms – such violations under Section 1 have to be justifiable in a free and democratic society and any actions undertaken under Section 1 have to be pursued in a reasonable and proportionate manner. And the Charter contains what some might term its own poison pill in the form of Section 33, a clause that sheepishly allows for governments to set aside all of the protections offered so loftily within the Charter itself.

“Notwithstanding” all those glorious commitments to justice and equality and other good things, any government can simply decide to act in ways that would be patently unconstitutional except that such behaviour is allowed for in the Charter itself. If your government is using Section 33 to pass certain legislation, you can be very sure that it’s because it’s bringing in legislation that doesn’t meet the test of Section 1 – it is not justifiable in a free and democratic society and/or it’s not being pursued in a reasonable and proportionate manner.

So, turning now to the situation in Ontario with the CUPE school board workers: Section 2 of the Charter lists all of our fundamental freedoms and 2 (d) is simple and profound “freedom of association”. Now if you’re not steeped in legalese, you might wonder how this translates into the right to strike, which is what Doug Ford’s Bill 28 tried to take away from CUPE’s school board workers. Well, here’s the thing: the Charter is spare and lean and elegant and it’s the job of governments to interpret it and apply it. And ultimately, it’s the job of our Courts to make sure that these interpretations are correct. Over the last 40 years, since the Charter was born, substantial work has gone into figuring out what any language in the Charter means in the real world. Section 2(d) of the Charter might sound like it means that five-year-old you can hang out with whomever you choose but in reality it is the right that allows us to associate with other people in trade unions and to negotiate with our employers collectively. Trade unions have been recognized and legal in Canada since 1872 – the first Canadian Trade Union Act was brought forward here just a year after a similar act was passed legalizing trade unions in the UK in 1871.

In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that workers have the right to collectively withdraw their labour – ie, go on strike. Writing for the majority of the Justices of the Supreme Court, Justice Rosalie Abella noted that the “Court has long recognized the deep inequalities that structure the relationship between employers and employees and the vulnerability of employees in this context”. Abella further confirmed the expansive rights-affirming view of the Charter, writing that it “seeks to preserve ‘employee autonomy against the superior power of management’ in order to allow for a meaningful process of collective bargaining.”

Justice Abella went on to note that the Charter’s values of “dignity, equality, liberty, respect for the autonomy of the person and the enhancement of democracy” supports the right to strike because [it] “is essential to realizing these values and objectives through a collective bargaining process because it permits workers to withdraw their labour in concert when collective bargaining reaches an impasse.”

Through a strike, workers come together to participate directly in the process of determining their wages, working conditions and the rules that will govern their working lives…. The ability to strike thereby allows workers, through collective action, to refuse to work under imposed terms and conditions. This collective action at the moment of impasse is an affirmation of the dignity and autonomy of employees in their working lives.” The Supreme Court ruled that the “ability to engage in the collective withdrawal of services in the process of the negotiation of a collective agreement is therefore, and has historically been, the ‘irreducible minimum’ of the freedom to associate in Canadian labour relations.”

We have in Canada the unquestionable right to strike as workers engaged in a process of collective bargaining. This was codified into the law by the 2015 Supreme Court ruling on the Charter that workers have the right to collectively withdraw their labour – ie, go on strike. The law is a site of struggle, sometimes in front of the courts, sometimes in the streets, sometimes in ballot boxes. Workers will do what they need to in order to protect themselves; we are not only dependent on legislation and court interpretations. But now that this right to strike has been codified into law by the Supreme Court, this right lies underneath every bargaining cycle for every unionized worker in Canada. Very few ever go on strike; but it’s a bit like an ambulance. If you were ever to need one, you’d want to know that you had access to one, right? And what Ford’s Bill 28 tried to do was remove all ambulances just at the moment when 55,000 workers needed them. CUPE’s 55,000 school board workers bargain patiently and when they couldn’t get anywhere with their employer, they provided the legally required notice to strike. Rather than continue to bargain, Ford and Education Minister Stephen Lecce tabled Bill 28.

I should note here that the notwithstanding clause has never been used in collective bargaining or in any back to work legislation passed in any of the provinces. It is a rare and exceedingly serious power that allows legislators to set aside the constitutional protections conferred upon the people. For Ford to use it in such a manner, essentially to overpower a group of workers who are looking for some wage gains to offset record levels of inflation, is such a flagrant misuse of his power that he managed to mobilize the entire labour movement, not just in Ontario but across the country.

If Ford’s Bill 28 was allowed to stand in Ontario, we all knew that every public sector bargaining table in the country would be under threat. If Ford was allowed to get away with such an attack on all workers, then every right-wing Premier in the country would have a nuclear option at their disposal in every round of collective bargaining with workers. It couldn’t be allowed to happen. It shouldn’t be allowed to happen. And as it turns out, it wasn’t allowed to happen.

Less than a week after Bill 28 was tabled, Canada’s labour movement rose to the challenge. The incredible organizing that happened within the labour movement demonstrates the seriousness – the existential nature, you might even say – of Bill 28, but is also a testament to the tenacity of the CUPE school board workers themselves who refused to be bullied into submission. CUPE’s 55,000 members swung into action for province wide political protests after Bill 28 was passed in the middle of the night after time limited sittings of the Provincial Parliament.

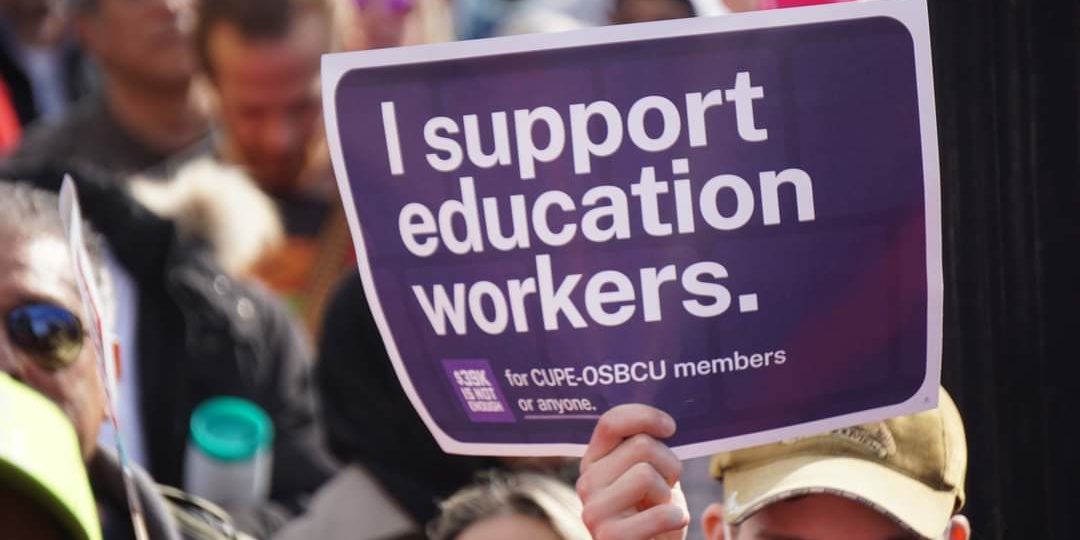

CUPE education workers were joined by OPSEU’s school board workers in a gallant show of solidarity. Parents, some with kids in tow, and friends and allies joined them. Protestors appeared in tiny towns at MPP’s offices and tens of thousands took to Queen’s Park. Speakers from organizations and coalitions big and small spoke to and for the school board workers whose rights were being blatantly violated and whose recourse to the Charter was being taken away from them. The protests carried on through the weekend – a rally and march in downtown on “Solidarity Saturday” drew thousands – and continued on into Monday.

The full throated response to Bill 28 from the union movement is a shining example of the spirit of solidarity that is the trade union movement at its very best.

On Monday morning, as CUPE workers and their allies flocked to protest at MPP’s offices and to Queen’s Park once again, a coalition of labour leaders from across the country, from public sector and private sector unions, were preparing to appear at a news conference to announce (as Unifor President Lana Payme shared) their unprecedented response to an unprecedented attack. At 9 a.m., barely an hour before the trade union press conference, Ford appeared in a hastily cobbled together presser of his own with an offer to rescind and repeal Bill 28. “I don’t want to fight,” he pleaded, not saying what we all know to be true: that he had tried to start a fight but had been overpowered by the working class finding its collective voice.

None of that would have happened without the incredible organization that CUPE education workers have been engaged in for years leading up to this round of bargaining. It is a testament to the work that these workers have done within their communities that so many people came out to stand with them and stand by them when they were suddenly caught up in a constitutional maelstrom which was far beyond the scale of their bargaining demands.

So with far more grace than Ford and his government deserve, CUPE’s school board workers accepted his offer to return to bargaining. As I write, the two sides are in bargaining, under a process this is still within the boundaries of the Charter. As OPSEU President JP Hornick said at the labour press conference, we are all now “standing by, not standing down” as we wait to see where this bargaining lands.