Jeremy Corbyn might have lost the last British election and then stepped down as leader of the Labour party, but he has not abandoned either politics or activism. Far from it.

Corbyn spoke with hundreds of Canadians this past weekend, in an online event organized to raise funds for Progressive International, a worldwide organization founded in September 2020, devoted to egalitarian, anti-colonialist, and democratic goals, on a global scale.

Corbyn answered questions from NDP MP Niki Ashton and from Canadian activists across the country.

For a man who has received more than his fair share of, in Shakespeare’s words, the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Corbyn has a cheerful, hopeful, sanguine and reflective manner.

During the afternoon’s event he elided effortlessly from the personal to the political. When talking about the environment, for instance, he referred to his own love of the flowers and fields of nature.

“As one who had the pleasure of growing up in the countryside in the English Midlands,” Corbyn told his Canadian audience, “I take joy in the glory of biodiversity, at the bees and ants and beetles and frogs and all the rest.”

But then came the more hard-edged political part: “Nature is not just for enjoyment. We need it. We can’t live without it.”

In talking about race and racism, Corbyn quoted friend, author, broadcaster and journalist Remi Kapo, who has written extensively about the history of the slave trade and the abolitionist movement.

Kapo, Corbyn said, “describes the utter brutality of the slave trade, where people go as slave hunters, into the forests, capture people, put them in chains, hold them in forts, and then load them onto ships.”

Corbyn then made a point of adding this chilling detail, from Kapo’s work:

“Before the slave ships sailed, a priest would come aboard and bless them and bless all the people on the ship for their journey — hundreds of people, manacled, many of whom would die before they reached their destination.”

Migrant workers, vaccine apartheid, and needing each other

The focus of this conversation with Canadians was on global issues.

Progressive International is built on the premise that it will be impossible to achieve social and environmental justice, and a fair and equitable distribution of wealth, only in a single country, or even region. We must strive to achieve those goals worldwide. Activists around the world have to find ways to work together — which is not always easy.

One Canadian activist who offered a message of solidarity during this event hit hard on the connection between the local and the global.

Chris Ramsaroop works with migrant workers through the organization Justicia For Migrant Workers. He explained how the abuse of tens of thousands of migrant workers reproduces within Canada, Europe and the U.S. an unjust, unfair and often brutal global economic system.

Ramsaroop referred to the “plantations” of wealthy countries, such as Canada, “where agricultural workers continue to be dehumanized and subject to dangerous conditions because of chemicals, pesticides, unfair working conditions and the inability to form unions.”

Corbyn then picked up and amplified Ramsaroop’s words.

“The message about agriculture is key. Agriculture should not be the most dangerous industry. You should not die from pesticides because you’re growing vegetables …”

From there, it was a short step to fighting for the rights of other key workers in the global supply chain, notably those of Amazon.

Progressive International, Corbyn said, is focusing global attention on Amazon’s well-documented disregard for its workers’ rights — a task Corbyn characterized as “very, very important.”

In offering her message of solidarity, writer and activist Naomi Klein focused on the current pandemic. She talked about the troubling and dangerous phenomenon of vaccine apartheid, fuelled by the power of transnational pharmaceutical corporations.

Corbyn’s response was to reflect on how the pandemic has exacerbated social and economic inequality both globally and locally.

“Lockdown has different meanings for different people,” he said. “In my community being locked down in a one-bedroom flat with three children, and schools closed, and having to teach your own children, is, to put it mildly, a bit tough …”

But then Corbyn pivoted to what he sees as a potentially more hopeful political consequence of the pandemic.

“I’ve been helping out with our local food hubs and food banks,” he said, “and there is an amazing number of people who come out to help each other who never thought they’d need help. They suddenly realize how much we depend on one another.”

The pandemic, Corbyn argued, has brought about a “massive political awakening” around the world.

People are coming to understand that working cooperatively is not just an idea. The current health crisis has shown them doing so can be a matter of life and death.

Not an excuse for austerity

At the level of politics and public policy, Corbyn warned that the rebuilding phase emerging from the pandemic must not be “an excuse for international austerity, cutting back on public spending for schools, hospitals and social services.”

It should, he says, “be a time for sustainable development for the future.”

Corbyn’s message for activists of all kinds is: “We must all be bold and assertive.”

The British politician is also keenly aware of the danger for progressives everywhere of losing touch with grassroots working-class people.

Corbyn related a conversation he had not too long ago with a U.S. Trump supporter, who told the former Labour party leader he supported Bernie Sanders before throwing in his lot with Donald Trump.

The Trump supporter’s reasoning was simple. Both the socialist Vermont senator and the billionaire who spouted populist rhetoric were, in his view, “anti-establishment.”

We cannot forget about such people, Corbyn said, nor should we dismiss them.

Corbyn knows whereof he speaks.

In the last British election, the Brexit issue, coupled with a vague economic nationalism proposed by Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, caused tens of thousands of longtime Labour voters to desert their party, many for the first time in their lives.

And so, Corbyn now emphasizes, when we consider policies such as the Green New Deal, we have to learn how to make them relevant, in a positive way, to people who work in factories, mills, and mines.

We have to combine the pursuit of workers’ rights and of economic justice — which should include a guaranteed livable income — with the goal of environmental sustainability.

If progressives cannot successfully answer that challenge, Corbyn seemed to say, they will fail.

Karl Nerenberg has been a journalist and filmmaker for more than 25 years. He is rabble’s politics reporter.

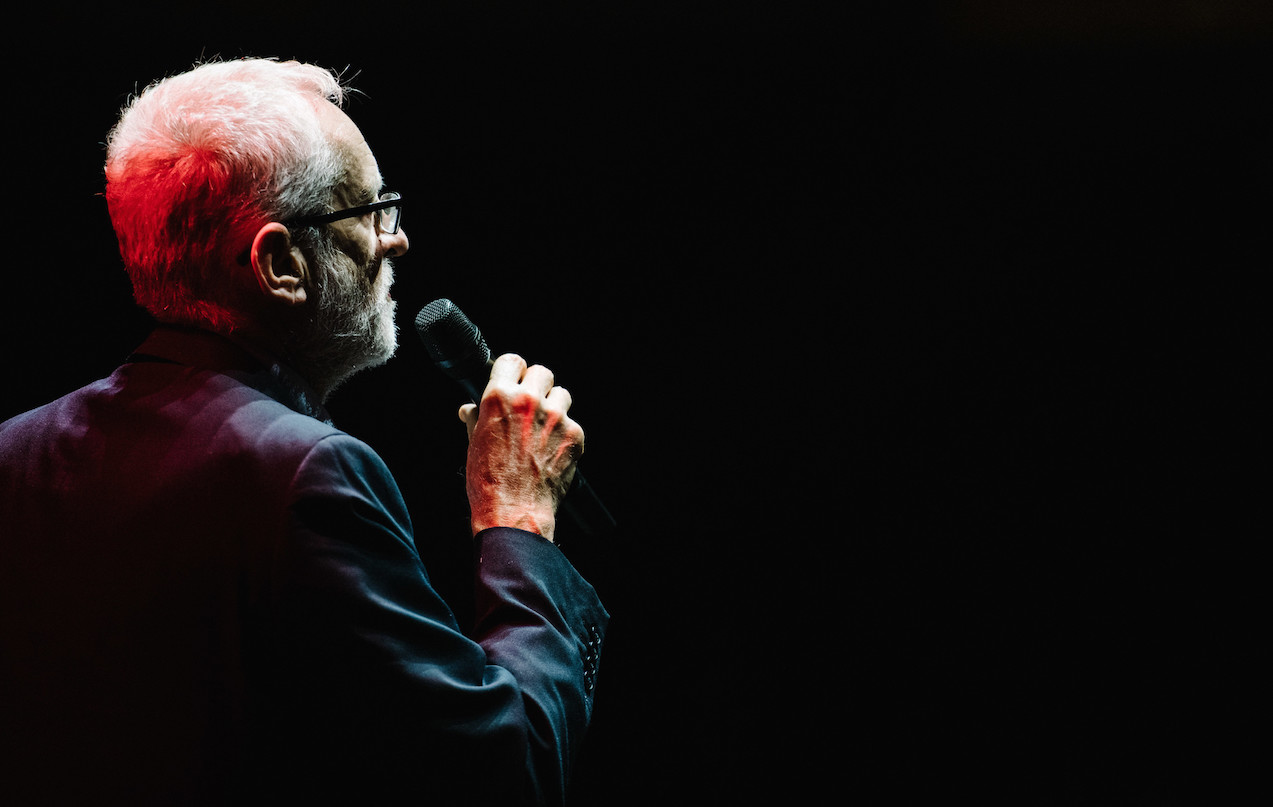

Image credit: Jeremy Corbyn/Flickr